Cathay Williams (1844 – 1892), a.k.a. William Cathay, was the first known African American woman to enlist in the United States Army, and the only black woman documented to serve in the US army in the 19th century.

Born as an enslaved person in Independence, Missouri in 1844, Cathay worked as a house servant on a nearby plantation on the outskirts of Jefferson City.

“While I was a small girl my (enslaver) and family moved to Jefferson City. My (enslaver) died there and when the war broke out and the United States soldiers came to Jefferson City they took me and other colored folks with them to Little Rock. Col. Benton of the 13th army corps was the officer that carried us off. I did not want to go.” ~ Cathay Williams

In 1861, the year the American Civil War began, Union forces occupied Jefferson City. During the Civil War, captured enslaved persons were considered contraband and were usually pressed into service supporting the military. Cathay was 17 years old when she was forced to work as a cook and washerwoman for the army. She traveled with an infantry regiment through many states, and was present at the Battle Of Pea Ridge, the Red River Campaign, and served briefly under General Philip Sheridan. She was working at Jefferson Barracks back in Missouri when the war ended in 1865.

After the Civil War, employment opportunities were scarce for many African-Americans, especially in the south. Many of them looked to military service, where they could earn not only steady pay but also education, health care, and a pension. Cathay had a cousin and a friend who enlisted, and she decided that in order to earn a living, she would enlist too.

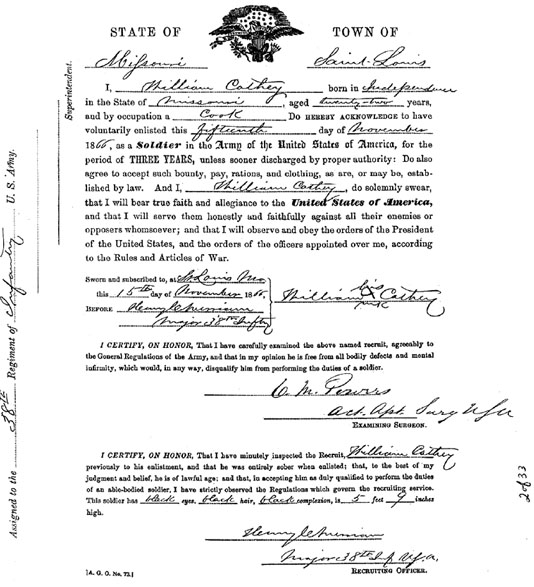

On November 15, 1866, Cathay Williams enlisted in the Army using the name William Cathay. She informed her recruiting officer that she was a 22-year-old cook. He described her as 5′ 9″, with black eyes, black hair and black complexion.

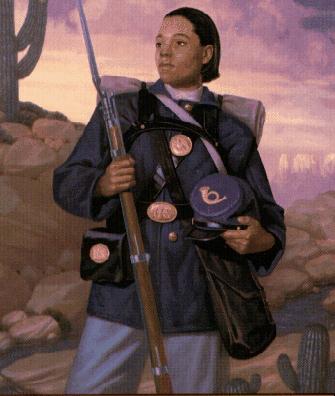

An Army surgeon examined Cathay and determined the recruit was fit for duty, thus sealing her fate in history as the first documented black woman to enlist in the Army even though U.S. Army regulations forbade the enlistment of women. She was assigned to the 38th U.S. Infantry and traveled throughout the West with her unit. During her service, she was hospitalized at least five times, but no one discovered she was a female.

“The regiment I joined wore the Zouave uniform and only two persons, a cousin and a particular friend, members of the regiment, knew that I was a woman. They never ‘blowed’ on me. They were partly the cause of my joining the army. Another reason was I wanted to make my own living and not be dependent on relations or friends.”

Finally, in October of 1868 — almost two years after she enlisted — the post surgeon discovered she was a woman and informed her commanding officer.

“The post surgeon found out I was a woman and I got my discharge. The men all wanted to get rid of me after they found out I was a woman. Some of them acted real bad to me.”

Cathay was immediately given a disability discharge. Her commanding officer, Captain Charles E. Clarke, stated that Cathay was “feeble both physically and mentally, and much of the time unfit for duty. The origin of his infirmities is unknown to me.”

At the time she had been stationed in New Mexico territory, so she went to work as a cook in Fort Union, New Mexico under her original name. She briefly married, but the union ended when he stole her money and horses and she had him arrested. Later she moved to Trinidad, Colorado where she became known as Kate Williams. She subsisted on odd jobs as a cook, laundress, and seamstress.

While living in Colorado, Cathay was approached by a reporter from St. Louis. He had heard rumors about the first black woman to serve in the US army, and had traveled to Colorado to interview her. He wrote an article about her life and military service which was published on January 2nd, 1876 in the St. Louis Daily Times.

“You see I’ve got a good sewing machine and I get washing to do and clothes to make. I want to get along and not be a burden to my friends or relatives.”

Cathay’s poor health continued even after she left the army: she suffered from neuralgia (at the time a catch-all term for various illnesses) and diabetes. She had several toes amputated due to diabetes, forcing her to use a crutch to get around. She also spoke of suffering from rheumatism and deafness. In 1891, at the age of 47, she applied for a disability pension for her military service.

The Army rejected her pension claim on February 8th, 1892, citing no grounds for a pensionable disability, but did not question her gender identity as William Cathay. The exact date of Cathay Williams death is unknown.

Sources:

http://www.amazingwomeninhistory.com/cathay-williams-american-civil-war-soldier/

http://www.army.mil/africanamericans/profiles/williams.html