“In such a wild country as Africa one does not go far without adventures. The traveler necessarily sees what is strange and wonderful, for every thing is strange.”—Paul du Chaillu

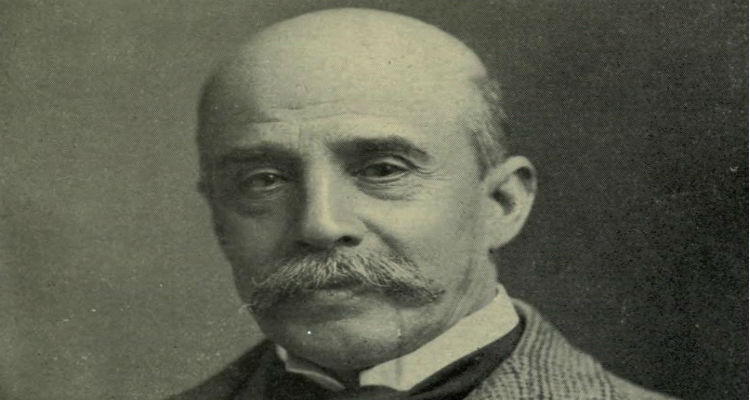

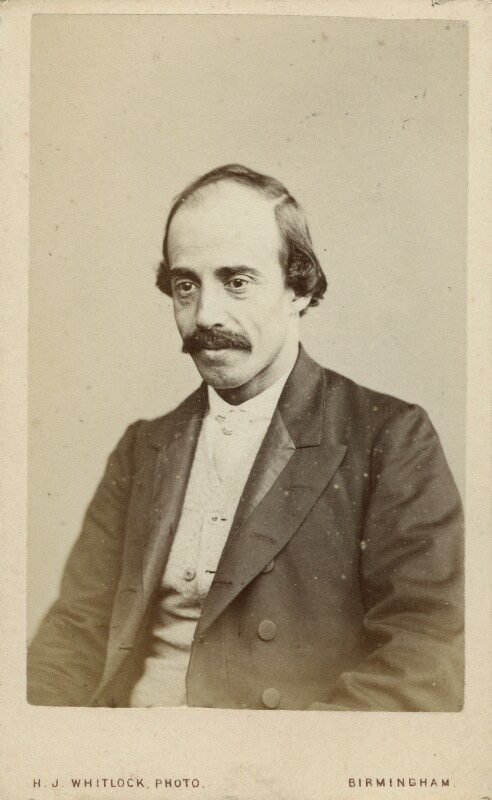

Paul Belloni Du Chaillu (du shay’ yu) was “an African traveler, discoverer of the gorillas, writer of children’s stories, and one of the most talked of men of his time.” Du Chaillu became famous in the 1860s as the first modern European outsider to confirm the existence of gorillas, and later the Khoi-San people of central Africa. However, his mother was a mixed-race woman of African-descent, which he kept secret. Du Chaillu traveled more than 8000 miles in Africa, killed and stuffed more than 2000 birds, gorillas, and other animals, and wrote hundreds of magazine articles and books. It has been claimed that he was the inspiration for the character Tarzan.

“Du Chaillu…contributed perhaps more than any other single individual to the opening up of Africa to Western Civilization. Livingstone, it is true, had preceded him; however, he not only preceded Livingstone into the deep interior but his books publicized Africa as it had never been before. His work paved the way for Henry M. Stanley and created a receptive public for the latter.” -J. A. Rogers, World’s Great Men of Color: Volume 1

Du Chaillu was probably born in 1837 on the island of Reunion off the east coast of Africa. His father who was French, owned a trading depot off the coast of Gabon and had friendly relations with most of the coastal people. Du Chaillu was sent to Paris for his education. He later returned to Africa and began like his father to trade with African people along the Gabon River in West Africa. His first venture ended in disaster; he nearly drowned and lost his entire cargo of ebony and ivory. Deserted by his men, Du Chaillu stumbled upon an American mission four days later. The missionaries painted such an attractive picture of America for him that he decided to go there to make his fortune.

With the money he had inherited from his father, Du Chaillu left for New York. In America, realizing that knowledge of his true ancestry would be fatal, he evaded talking about the place of his birth. Although his skin was dark, his straight hair and French accent made people believe that he was from New Orleans. However, he could not always escape suspicion. One night in midwinter some of the European men in the lodging house in which he lived decided to “teach him a lesson.” They planned to tie him up and threw him down a steep incline into the icy water of a lake. Du Chaillu warned of this, went out, and returned with a good supply of roast turkey, cake, pie, candy, and fruits. When his would-be tormentors appeared, he invited them in courteously and asked them to join him in supper. They ate and bothered him no more.

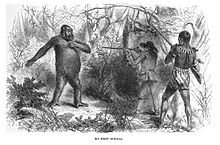

Du Chaillu’s great ambition was to be a writer. He had known about the gorilla and thought that the American public would be interested in it, and therefore began taking lessons in natural history. In 1855, at the age of 20, he was sent by the Academy of Natural Sciences at Philadelphia on an African expedition, to find the gorilla, which no European had ever seen. The equatorial regions of Africa were so inhospitable for Europeans that the area was known as “The whyte man’s grave”. Also, the largest specimens of anthropoid apes then known were the orangutan and the chimpanzee. In 1847 an American missionary had told of an ape in the jungles larger than either of these two species, but the public and even scientists did not believe, even though there were two incomplete skeletons of the gorilla in museums.

Until 1859, Du Chaillu explored the regions of West Africa in the neighborhood of the equator, gaining considerable knowledge of the delta of the Ogooué River and the estuary of Gabon. He studied plant and animal life, cultural customs, geography, and collected samples of dozens of unknown species. He made maps, went on hundreds of hunting expeditions, lived in African villages, learned several new languages, spoke with the people about their beliefs and customs, and kept careful records of all his observations. During his travels from 1856 to 1859, he observed numerous gorillas. However, he experienced many hardships, including hunger. At first, he refused to eat roasted snakes and monkeys; attempting to still his hunger by drinking liquor. But, he finally was forced to eat monkey to keep from starving which he developed a taste for. He fell seriously ill with bush fever. He and his party also narrowly escaped being devoured by a horde of ants on the march, and being torn to pieces by a band of infuriated women whose sacred dance he had spied on. After four years, Du Chaillu was forced to quit because of swollen feet. He returned to America, loaded with dead specimens, and presented himself as the first whyte European person to have seen the gorillas.

Overnight, Du Chaillu became the most widely talked of man in Europe and America. Learned societies showered him with invitations and leading scientific journals carried his articles. The Royal Geographical Society, then the most powerful institution of its kind, invited him to England, where he was warmly welcomed. He showed his specimens of the gorilla to British scientists, after which the British Museum bought them for a large sum and a publisher gave him a large price for his manuscripts. His book, Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa (1861), became the best seller of the day. However, the book was so full of astounding adventures and unfamiliar customs that it was met by disbelief by many people until his findings were substantially confirmed by later explorers.

“I traveled—always on foot, and unaccompanied by other European men—about 8,000 miles. I shot, stuffed, and brought home over 2,000 birds, of which more than 60 are new species, and I killed upwards of 1,000 quadrupeds, of which 200 were stuffed and brought home, with more than 60 hitherto unknown to science. I suffered fifty attacks of the African fever, taking, to cure myself, more than fourteen ounces of quinine. Of famine, long-continued exposures to the heavy tropical rains, and attacks of ferocious ants and venomous flies, it is not worth while to speak.”—Paul du Chaillu, Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa

Du Chaillu returned to Africa in 1864. This time he intended to cross the interior of equatorial Africa on foot, with a band of about a dozen African porters. This expedition, however, was beset with difficulties, and he was obliged to return to the coast after only two years of taking photographs and sending back specimens. He was also able to confirm the accounts given by the ancients of the Khoi-San people inhabiting the African forests.

Du Chaillu returned to America, and in 1867 wrote his second book A Journey to Ashango Land. While in Ashango Land in 1865, he was elected King of the Apingi people.

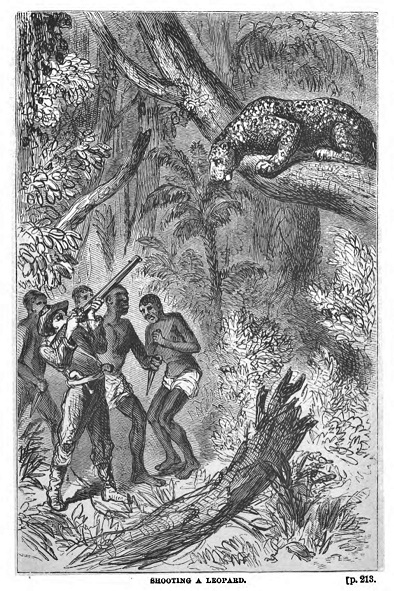

Du Chaillu then spent the next five years (1867-1871) writing a very exciting series of adventure books for young people based on his travels, complete with carefully crafted illustrations. The first two books, Stories of the Gorilla Country and Wild Life Under the Equator, recount various episodes from his years in Africa, including both of his major expeditions as well as his teenage years. His two subsequent books, Lost in the Jungle and My Apingi Kingdom, give a chronological account of his first expedition, and the fifth book, The Country of the Dwarfs, deals exclusively with his ill-fated second expedition.

The books were immensely popular! Boys and girls over the English-speaking world read them eagerly, learning whole passages by heart. There were but few persons in the United States who did not know of Cousin Paul, or Ami Paul, as Du Chaillu was affectionately called.

However, writing his books did not cure Du Chaillu’s wanderlust. His next field of research was Scandinavia. He spent the next few decades traveling extensively in Sweden, Norway, Lapland, and Finland, gathering material for a book on the Vikings. When he reached Sweden in 1871, he was received with a guard of honor and escorted to the king’s palace. Du Chaillu coined the phrase “Land of the Midnight Sun”, which was the name of one of his major works on his northern explorations, the other being The Viking Age (1889). He wrote only one book for children regarding his northern travels, The Land of the Long Night (1899).

After the death of his good friend Judge Daly, Du Chaillu decided to visit Russia to study the life of the peasants there. Arriving in Russia in 1901, he was received as a hero. On April 29, 1903, he was stricken with paralysis and died. His body was placed in a vault for distinguished men of science and was later shipped to New York, where it was interred in Woodlawn Cemetery on June 25, of that year.

NB: Du Chaillu’s date of death is also given as 30 April, 1903.

Source:

World’s Great Men of Color by J. A. Rogers

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Du_Chaillu

http://www.mainlesson.com/displayauthor.php?author=chaillu