[dropcap size=small]W[/dropcap]illa B. Brown was the first African-American woman to become a licensed pilot in the United States. She was also the first Black officer of the Civil Air Patrol, and the first woman in the United States to possess both a mechanic’s license and commercial license in aviation. Brown was also an activist. Her contributions to the growing field of aviation led to many changes, including the integration of the United States military.

Willa Beatrice Brown was born on January 22, 1906, in Glasgow, Kentucky. The daughter of Reverend and Mrs. Erice B. Brown, she graduated from Wiley High School in Terra Haute, Indiana. She then attended Indiana State Teachers College earning a bachelor’s degree in business, in 1927. Immediately upon graduation, Brown found employment as a teacher in Gary, Indiana, where she met and married her first husband, Wilbur Hardaway, an alderman; the marriage was short lived.

In 1932, Brown moved to Chicago, Illinois, to become a social worker. After teaching for two years, she returned to school, attending Northwestern University, where she received an MA in business in 1937. During her student days, she taught and worked at a variety of jobs. However, it was in Chicago that she decided to learn how to fly. In 1934 Brown began her flight instruction under the direction of John Robinson and Cornelius Coffey. She also studied at the Curtiss Wright Aeronautical University and in 1935 earned a Masters Mechanic Certificate.

Brown was greatly influenced by Bessie “Queen Bess” Coleman, the first black female pilot. Due to racial and gender discrimination in the United States, Coleman was forced to obtain her license in France, through the Ecole d’Aviation de Freres Caudron, becoming the first black female pilot in the world. By the time Brown began to take flying lessons in 1934, several women, including Louise Thaden, Katherine Cheung (the first woman of Chinese ancestry to obtain a license), Phoebe Fairgrave Omelie, and Ann Morrow Lindbergh, had broken the gender barrier in the United States. Nevertheless, in 1937, Brown became the first black woman to break the racial barrier and obtain an aviator’s license in the United States.

Two years later she married her former flight instructor, Cornelius Coffey, and they co-founded the Cornelius Coffey School of Aeronautics, the first black-owned and operated private flight training academy in the U.S.

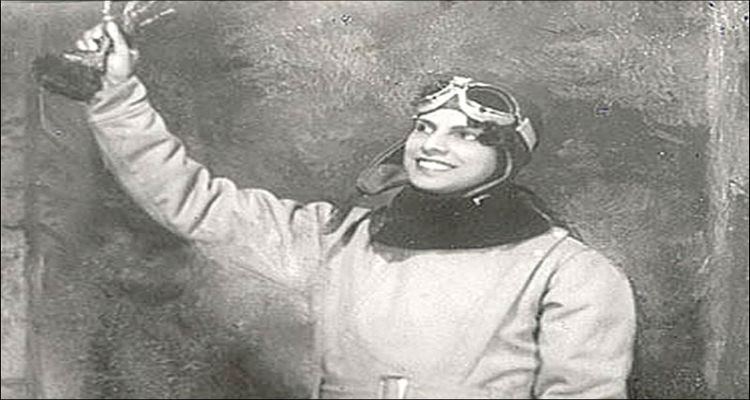

Brown was also a tireless promoter of the positive role that African Americans could play in aviation. She began participating in various flying events such as the Memorial flight for Bessie Coleman and air shows that featured entertaining flight demonstrations. Brown was also a self-promoter by many accounts. One such account, involved Brown seeking news coverage for a [African-American] air show in 1936. Brown, who was tall, beautiful, and often wore the typical flight apparel of the day—a jacket, jodphurs, and boots—decided the best way to get the media interested in the show was to go to the media first instead of getting them to come and see her. Hence, she visited the Chicago Defender newspaper office. She was so striking and had such a strong presence that everyone stopped what they were doing and stared at her. She announced who she was, stating that she was an “aviatrix” and described the upcoming show. Her tactic resulted in an audience between two to three hundred people. The event was also covered by Enoch P. Waters, a journalist who, in 1939, along with Brown and Coffey, co-founded the National Airmen’s Association of America (NAAA), an organization established and designed to facilitate the acceptance of Blacks into the United States Air Force. Waters continued to cover most of Brown’s recruitment activities for several years, with the support of the Chicago Defender’s editor, Robert Abbott.

In 1938, she and Coffey participated with other Black flyers in a Chicago airshow held at Harlem Airport. Before a crowd estimated at 30,000, Black aviators took first and second place in the first airshow in the U.S. where the races competed together.

In 1939, the Coffey school was awarded a contract by the Federal Government to train Americans to fly airplanes in case of a national emergency. Brown, having co-funded the NAAA, also joined the Challenger Air Pilot’s Association, the Chicago Girls Flight Club, and purchased her own airplane all between 1939 and 1940.

By 1941, hundreds of men and women had trained under Brown, including many men who later became members of the famed Tuskegee Airmen. Brown was the director/coordinator of two Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) programs: one at the Harlem Airport and the other at Wendell Phillips High School in Chicago. Brown achieved another distinction in 1941, when she became the first African-American officer in the U.S. Civil Air Patrol (CAP); she was commissioned a Lieutenant. The U.S. government also named her federal coordinator of the CAP Chicago unit. In 1943, Brown earned her mechanic’s license, becoming the first woman in the United States to have both a mechanic’s license and a commercial pilot’s license.

The Coffey School of Aeronautics closed in 1945, shortly after the end of World War II. Brown, a tireless recruiter, went on to establish flight schools for children. She remained an activist, both in aviation organizations and politically, running for a U.S. Congressional seat in 1946, 1948, and in 1950. Although Brown did not win these elections, she attained another status as doing something “first”—she was the first black woman to run for Congress. In 1955 Brown married her third husband, the Reverend J.H. Chappell. During her marriage to Chappell, Brown became very active in the Westside Community Church in Chicago. She taught in the Chicago public school system until 1971, when she was sixty-five years old. The following year, Brown was appointed to the FAA’s Women’s Advisory Board for her contributions to the aviation industry.

Willa Brown did not have any children. She died of a stroke in Chicago on July 18, 1992.

Source:

http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-2874200022.html