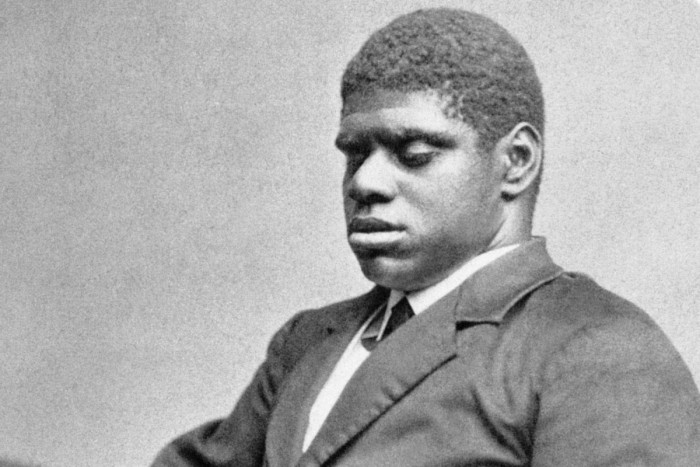

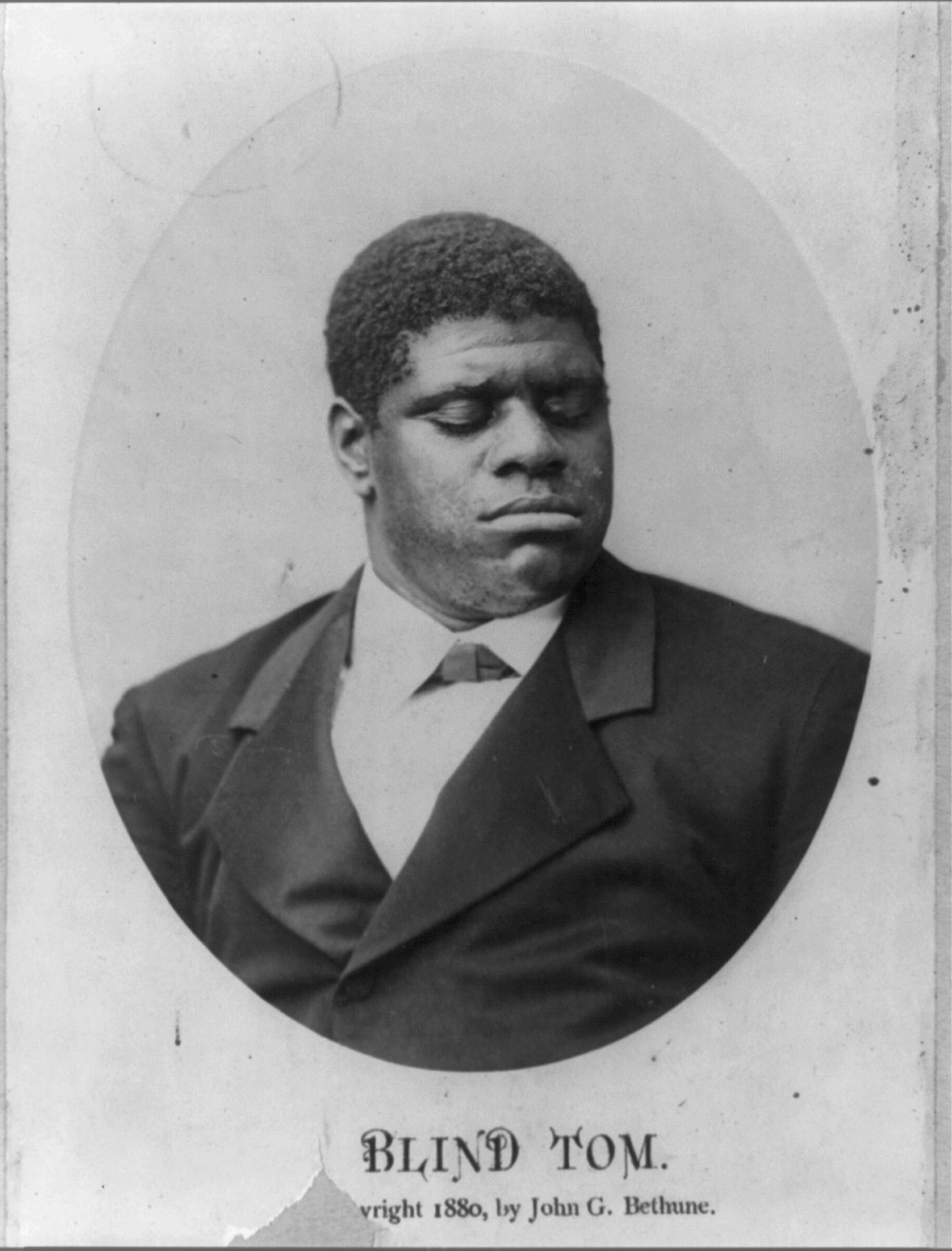

One of the most famous American entertainers of the nineteenth century, Thomas “Blind Tom” Wiggins was an African American musician and composer. Blind from birth and born into the Maafa (slavery), Wiggins became well known for his piano virtuosity. Though undiagnosed at the time, it is likely that he was autistic or an autistic savant as well.

Thomas Greene Wiggins was born near Columbus on May 25, 1849, to Charity and Domingo Wiggins. Domingo Wiggins, a field enslaved person, and his mother Charity Greene were purchased at auction by James Bethune of Columbus, Georgia when Tom was an infant. Domingo and Charity’s former master thought the blind sickly “pickaninny” had no labor potential and he was thrown into the sale as a no cost extra. Although Tom’s parents were married, the prevailing custom of the time dictated that female enslaved persons and their children retain the names of their owners. Following slavery tradition, Tom received the name Thomas Greene Bethune.

Some accounts of James Bethune accord him the salutary title of Colonel; others, General. However, according to Bethune family member Patti Andrews, Bethune held the military rank of Lieutenant in the Lawhons County, Georgia Volunteers. Bethune was a veteran of the Indian Wars, a practicing lawyer and a newspaper editor at the Columbus Times. He later published his own secessionist newspaper called the Cornerstone–one of the first publications to advocate secession for the South.

For the first several years of his life, Tom’s only sign of human intelligence was his interest in sounds–any sound–and an uncanny ability to mimic them. Charity was allowed to bring Tom with her to the main house where she worked for the Bethune family–a family of seven musically talented children who overflowed their home with singing and piano playing. When the Bethune children practiced their piano lessons, Tom listened. Once given access to the keyboard by himself, Tom astounded the family–his small hands and fingers able to reproduce the sequence of chords from his memory exactly as he had heard them played. General Bethune told Charity that her son had as much intelligence as the family dog and he began teaching Tom to respond to animal commands like “sit” and “stand.” Members of the Bethune family delighted in teaching their family pet the names of objects that he could feel and smell.

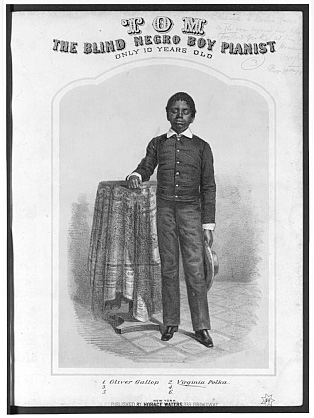

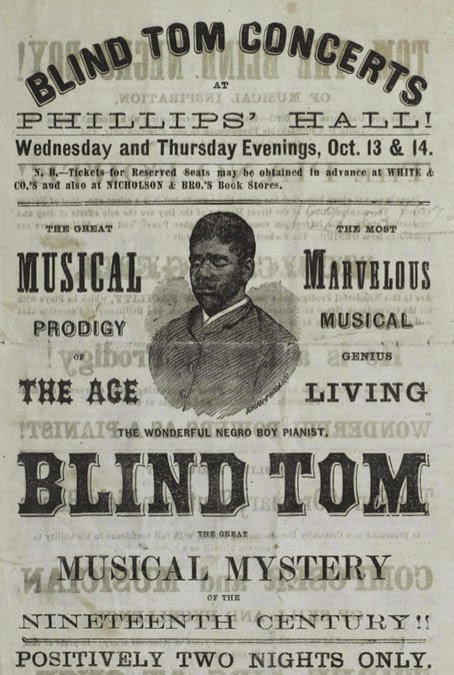

By age of six Tom started improvising on the piano and creating his own musical compositions. He claimed the wind, or the rain, or the birds had taught him the melody. Even though a local music teacher told Bethune that Tom’s musical abilities were beyond comprehension and his best course of action was simply to let him hear fine playing, Bethune provided Tom with various music instructors. One of Tom’s music teachers later reported that Tom could learn skills in a few hours that required other musicians years to perfect. In October 1857, General Bethune rented a concert hall in Columbus and for the first time “Blind Tom” performed before a large audience that had difficulty comprehending how a blind “idiotic slave” child could master the piano keyboard.

Enslaved persons with musical talent meant income for their owners and in 1858 James Bethune “hired out” Tom to concert promoter Perry Oliver for a period of several years. It has been estimated that Bethune pocketed $15,000 from the arranagement and that Perry Oliver made profits amounting to $50,000. Tom, now age nine, was separated from his family and exhibited throughout hundreds of cities on a rigorous four-shows-per-day schedule.

Not only could Tom perform world classics, he would astound his audiences by turning his back to the piano and giving an exact repetition–a reversal of the keys the left and right hands played. Musicians in the audience were invited to challenge Tom to a musical duel. Tom could successfully reproduce on the keyboard any piece of music a challenger would first perform. And taking that feat one step further–Tom could play a perfect bass accompaniment to the treble played by someone seated beside him–heard for the first time as he played it. Tom would often push the other performer aside and repeat the entire composition alone. When audiences applauded, Tom followed suit–mimicking the sounds of approval.

Blind Tom became so renowned that U.S. president James Buchanan invited him to Washington, D.C., and he became the first African American musician to perform at the White House. On one tour, he crossed paths with the writer Mark Twain, who was himself on a speaking tour. Twain was so enthralled with Wiggins’s remarkable abilities that he attended three performances in a row in 1869.

Blind Tom’s performances invariably contained a challenge, in which an audience member was brought onstage to play the most difficult piece of music he or she could. Blind Tom would stand by, wringing his hands and making improbable one-footed leaps in the air, anticipating the challenge, and naming each note as it was played. He then retook the piano and played the piece back exactly as he had heard it, flaws and all. He could also play different pieces of music with each hand while singing a third, all in different keys.

In 1861 Blind Tom was on tour in New York when Georgia seceded from the Union. He and his manager returned south, and his manager scheduled a number of events that would raise money for the Confederate cause. Inspired by what he heard of the war, the fifteen-year-old Wiggins composed his most famous piece, “The Battle of Manassas,” a song evoking the sounds of battle interspersed with train sounds and whistles, which Wiggins made himself. One biographer wrote that Blind Tom’s “perfect pitch, hypersensitive clarity, elastic vocal chords, lack of inhibition and total immersion in the world of sound enabled him to re-create a ‘harum-scarum’ battlefield like no other.” Many of the proceeds from his concerts during this period went to help sick and wounded Confederate soldiers.

Wiggins’s lack of emotional development coupled with extraordinary musical ability made him prime for exploitation. After the Civil War (1861-65) Bethune’s son, John, took over the management of Blind Tom, and he used Wiggins’s considerable income to support his own extravagant lifestyle. This continued guardianship of Blind Tom by the Bethune family following emancipation caused some to refer to Wiggins as “the last slave.” For a number of years John Bethune and Blind Tom toured the United States together. Bethune hired a manager to tour with Wiggins during the seasons he was unavailable, but Bethune continued to tour on and off with Wiggins until Bethune’s death in 1884. A series of messy court cases transferred the care of Blind Tom to Bethune’s estranged wife, Eliza, in 1887.

In an effort to take control of Wiggins’s income, Eliza Bethune persuaded his mother to officially sign over all of his rights to her, and Wiggins moved with Bethune when she relocated to New York. For several years Charity Wiggins also lived with her son in Bethune’s New York home.

On July 30, 1887, a federal court ordered General Bethune to surrender Tom at Arlington, Virginia into the hands of Charity and his former daughter-in-law Eliza Bethune. Newspapers reported Tom, disappointed and grief stricken at the thought of having to leave Virginia and the old General, was threatening to “fight them all.”

On the date of surrender, General Bethune’s son James brought Tom to the court room. The family who had made a fortune estimated at $750,000 at the hands of Blind Tom gave possession of him over to his mother Charity–a mother he hardly knew. Tom, who brought with him nothing more than his wardrobe and a silver flute, offered no resistance when he boarded the train to leave Virginia for New York and a home with Eliza. However, the word “lawyer” had become a bugaboo for Tom who had never really understood what the word meant but now associated it with men who caused big troubles and things unpleasant.

One month later, Tom was again on the concert stage showing no signs of emotional trauma from his latest custody battle. Now a source of income for Eliza who promoted him as “the last slave set free by order of the Supreme Court of the United States,” Tom’s performances continued throughout the United States and Canada. He now performed under his father’s surname as Thomas Greene Wiggins. With the exception of his brief reunion with Charity who soon returned to Georgia, nothing else had changed. Tom spent the remainder of his life in the care of Eliza.

Performances, concerts and vaudeville acts continued until 1904. His last days were spent in seclusion playing the piano and holding imaginary receptions. Tom died at age fifty-nine on June 13, 1908 at Eliza’s home in Hoboken. A few days later The New York Times headline read “BLIND TOM, PIANIST, DIES OF A STROKE — A CHILD ALL HIS LIFE.”Newspaper coverage reported that Eliza laid Tom to rest in Evergreens Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

Noted Kentucky newspaper editor Henry Watterson wrote one of the most touching tributes to Tom after the wires spread the news of his demise. “What was he? Whence came he, and wherefore? That there was a soul there, be sure, imprisoned, chained in that little black bosom, released at last.”

There is considerable debate, however, about his burial site. Initially he was interred in the Evergreens Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York, though some argued at the time that the body buried there was not Blind Tom’s. Others believe that Wiggins was initially buried there but was later exhumed and reinterred near his birthplace in Columbus. Today, two plaques, one in Brooklyn and another in Columbus, mark the possible resting places of Blind Tom.

Blind Tom’s story became the subject of great interest around the turn of the twenty-first century. Articles about him have appeared in such periodicals as the New Yorker and the Oxford American, and in 1999 pianist John Davis made a new recording of fourteen of Blind Tom’s original pieces. In 2002 the 7 Stages Theatre in Atlanta produced a play based on Wiggins’s life entitled Hush: Composing Blind Tom Wiggins. Columbus State University holds a small collection of Blind Tom’s original sheet music.

Sources:

http://www.twainquotes.com/archangels.html

http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/arts-culture/thomas-blind-tom-wiggins-1849-1908