The Lincoln Motion Picture Company was the first movie company organized by Black filmmakers, and developed a solid reputation for producing films that, according to one Black observer,

“ . . . proved a revelation to those who have never seen our folks in anything but ‘comedies’ . . .”

Lincoln was organized on May 24, 1916, by actor Noble Johnson, who served as president of the company. The secretary was Clarence A. Brooks, also an actor. Dr. James T. Smith, a well-to-do druggist, served as treasurer and Dudley A. Brooks was the initial assistant secretary of the company. Formal California incorporation was granted on January 20, 1917, with the value of produced films and equipment appraised at $15,623.68 by Henry McRae, manager of production at Universal, and actor Harry Carey, who often used Noble Johnson as a character actor in his films (Johnson’s film career in Hollywood began in 1913 and included a small role in Cecil B. DeMille’s The Squaw Man).

On April 30, 1917 the Lincoln Motion Picture Company was given approval to issue 25,000 shares of common stock.

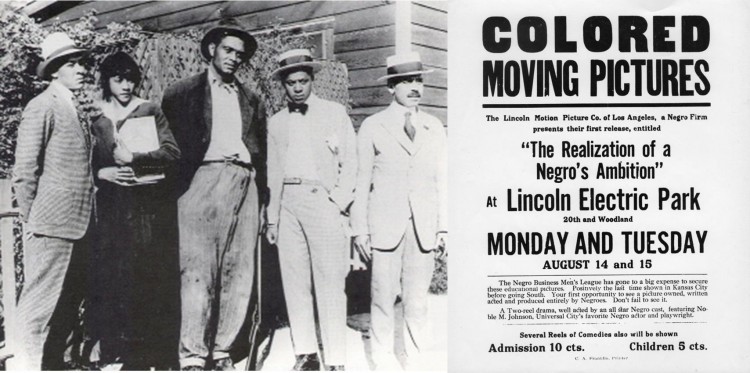

The first Lincoln production was The Realization of a Negro’s Ambition (released in mid 1916), a two-reel film which company publicity releases proclaimed was a “Drama of love and adventure, a picture with a good moral, a vein of clean comedy and beautiful settings.” The plot concerned a young engineering graduate of the Tuskegee Institute who leaves the family farm to try his hand in the oil fields of Los Angeles. Turned away because he is Black, the young man rescues a white woman in a runaway carriage. She turns out to be the daughter of the oil company owner, who offers the young man a job with the company’s oil exploration team. Later, the young engineer realizes that his parents’ farmland shows oil possibilities, and the company owner bankrolls the exploratory drilling tests that eventually prove successful.

Lincoln Motion Picture Company’s second film focused on the massacre of African-American troops in the U.S. Army’s 10th Calvary against Mexican revolutionary figures in 1916. The movie held its opening at the New Angelus, an all-black theater in 1917. The film ran for a week with an almost full house. In cities such as Chicago and Oakland, the film played to full houses. And in the city of New Orleans, it was shown to mixed race audiences at the New Ivy and People’s theaters. The screenings in these venues in New Orleans was groundbreaking because it was the first time a film featuring an African-American cast and film production staff was played.

Marketing of the Lincoln productions was entrusted to Noble Johnson’s brother, George Johnson, a postal clerk who lived in Omaha, Nebraska. Although the Johnson brothers hoped the films would play to wider audiences, they were mostly booked to play in special venues at churches and schools and the few “Colored Only” theaters.

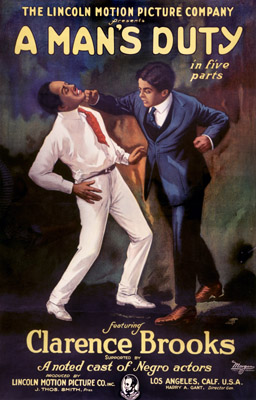

By 1920 the Lincoln company had completed five films, two pictorial and three dramatic subjects, including a five-reel feature titled A Man’s Duty (released September, 1919), but it proved to be a marginal operation. Although he retained his stock, Noble Johnson was forced to give up his presidency of the company as he became an established contract player at Universal. James T. Smith was elevated to the presidency.

According to George Johnson, “The national demand for more Lincoln productions was so great that the Lincoln management chose not to wait on the returns from the films already produced to make another one; but to accept an offer for financial backing offered by a white financier, P. H. Updike, in Los Angeles, California.”

George Johnson applied for a medical leave of absence from his postal job on grounds of overwork and came to Los Angeles to supervise the marketing and promotion of what would become Lincoln’s most ambitious project.

“Leaving wife and infant daughter alone in Omaha,” George Johnson recalled in the 1930’s, “I left for Los Angeles taking a copy of A Man’s Duty and showing it on a percentage (which meant I had to be in the theatre at the showing to collect the 60% of the receipts due, and then take the film and move it to the next town). On this trip I showed the film in Topeka, Kansas; Muscogee, Oklahoma; Dallas, Fort Worth, and El Paso, Texas.”

Renting stage space in the Berwilla Studio at 5821 Santa Monica Boulevard in Hollywood, the Lincoln Motion Picture Company began production on the six-reel drama By Right of Birth (released October, 1921), with a script by Dora Mitchell based on a story by George Johnson. Clarence Brooks starred, Anita Thompson played the female lead. Booker T. Washington was also seen in a cameo role. Although the Lincoln Film Company was managed by Blacks, the direction and cinematography of this film, and most of the other Lincoln productions, was entrusted to white cameraman Harry Gant, who was also a stockholder in Lincoln, and who later produced and directed low-budget Westerns.

Despite the fact that he had financed the production, P.H. Updike had grave doubts about By Right of Birth as a commercial proposition. “Our backer, Mr. Updike, was worried as he did not see how we were going to make money showing the film in small Negro theaters. So it was up to Johnson to convince him,” wrote George Johnson in later years.

Johnson rented the Trinity Auditorium (now the Embassy Auditorium) in the Embassy Hotel in downtown Los Angeles for the evenings of June 22 and 23, 1921. Johnson divided the house into ten sections and “engaged ten of the prettiest girls we could find” to sell tickets. In two weeks the women managed to sell out the two performances. The affair was a success, but the effort did little to improve the overall commercial prospects for the film. The Lincoln Motion Picture Company began its existence with great expectations. White audiences were needed and simply were not interested at the time.

According to Johnson, the premier was a gala affair. “We had a footman in uniform outside for auto patrons,” he remembered, “and a prologue with music by Webb Spike’s band of 30 pieces; and a program of songs and dances. In the audience we had representatives from two Negro newspapers and three white, Sunshine Sammy Morrison and quite a number of noted white and colored actors from Hollywood.”

The event was a success, but the effort did nothing to enhance the overall bleak commercial prospects for the film. The Lincoln Motion Picture Company began its brief existence with great optimism. An investment brochure declared, “The Company will not only produce pictures entertaining to Negroes but to all races. Our market is as large as we make it; the world is our field . . .” But an added note suggested the grim reality: “We are not only booking our pictures in theatres, but road men are being equipped for showing in churches, halls, schools and smaller towns that have no theatres, thereby reaching millions of people that would not otherwise be reached.”

Without a wider audience, the Lincoln Motion Picture Company was doomed to failure and “By Right of Birth” proved to be the company’s swan song. The Lincoln Motion Picture Company lasted until 1921.

Sources:

http://afroamhistory.about.com/od/africanamericanculture/a/Lincoln-Film-Company.

http://www.hollywoodheritage.com/newsarchive/summer01/birchard.html

http://www.aaregistry.org/historic_events/view/lincoln-motion-picture-company-first-black-cinema