Learie Nicholas Constantine, Baron Constantine, Kt. was a West Indian cricket legend, barrister, author, broadcast journalist and political activist who served as Trinidad’s High Commissioner to the United Kingdom and became the UK’s first Black peer. He played 18 Test matches before the Second World War and took the West Indies’ first wicket in Test cricket; his performance at Lord’s in 1928, where he took 100 wickets and made 1,000 runs – led to an invitation to turn professional and join the Nelson team in the Lancashire League. An advocate against racial discrimination, in later life he was influential in the passing of the Race Relations Act in Britain. He was knighted in 1962 and made a life peer in 1969.

Constantine was born in Petit Valley, a village close to Diego Martin in north-west Trinidad, on 21 September 1901, the second child of the family and the eldest of three brothers. His father, Lebrun Constantine, was the grandchild of the enslaved. Lebrun rose to the position of overseer on a cocoa estate in Cascade, near Maraval, where the family moved in 1906. Lebrun was famous on the island as a cricketer who represented Trinidad in first-class cricket and toured England twice with a West Indian team. Constantine’s mother, Anaise Pascall, was the daughter of the enslaved; and her brother Victor, was also a Trinidad and West Indian first-class cricketer; in addition, a third family member, Constantine’s brother Elias later represented Trinidad. Constantine wrote that although the family was not wealthy, his childhood was happy. He spent a lot of time playing in the hills near his home or on the estates where his father and grandfather worked. He enjoyed cricket from an early age; the family regularly practised together under the supervision of Lebrun and Victor Pascall.

Constantine first went to the St Ann’s Government School in Port of Spain, and then attended St Ann’s Roman Catholic School until 1917. He displayed little enthusiasm for learning and never reached a high academic standard, however showed prowess at several sports and was respected for his cricketing lineage. He played for the school cricket team, which he captained in his last two years, by which time he was developing a reputation as an attacking batsman, a good fast-medium bowler and an excellent fielder. His father prohibited him from playing competitive club cricket until 1920 for fear of premature exposure to top-class opposition while too young; in addition, he first wanted his son to establish a professional career. Upon leaving school Constantine joined Jonathan Ryan, a firm of solicitors in Port of Spain, as a clerk. This was a possible route into the legal profession; however, as a member of the Black lower-middle class, he was unlikely to progress far. Few Black Trinidadians at this time became solicitors, and he faced many social restrictions owing to his colour.

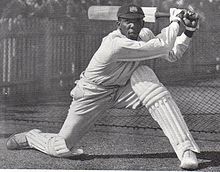

Constantine later followed in his father’s footsteps and became a first-class cricketer for the West Indies Cricket Team; in 1923 the young Constantine played with his father, against British Guiana, in Georgetown – one of only a few occasions when a father and son have appeared together in a first-class match. As a cricketer Constantine became one of the most exciting all-rounders and one of the most exceptional fielders that has ever appeared in the game, and was a member of the West Indies teams that toured England in 1923 and 1928.

Unhappy at the lack of opportunities for Black people in Trinidad, he decided to pursue a career as a professional cricketer in England, and during the 1928 tour was awarded a professional contract with the Lancashire League club Nelson. He was paid £500 a year to be a professional cricketer. In 1930, playing for the West Indies against England, Constantine bowled the West Indies to their first Test Match win. He played for the club with great distinction between 1929 and 1938, while continuing as a member of the West Indies Test team in tours of England and Australia. Although his record as a Test cricketer was less impressive than in other cricket he helped to establish a uniquely West Indian style of play. His play in the Lancashire Cricket League was so outstanding that he was awarded the Wisden Cricketer of the Year in 1939.

He settled in Lancashire with his wife and daughter. Constantine met his wife, Norma Agatha Cox, in 1921. She initially had little interest in cricket, and later she began to take more of an interest in his sporting achievements. They were married on 25 July 1927; their only child, Gloria, was born in April 1928. Throughout their marriage, his wife motivated him to continue his efforts to further his career and they remained close.

Black people were a novelty in Lancashire, and they had to endure rudeness, anonymous letters and general curiosity. But they stuck it out, eventually winning the respect, admiration and friendship of the locals. CLR James was their lodger for a while, and helped Constantine write his first book, “Cricket and I”, in 1933. And during his nine years with the Nelson team, they won the league championship seven times.

In 1942, while working in a solicitor’s office, Constantine was asked by the Ministry of Labour to become a temporary civil servant in its welfare department, with responsibility for the West Indian technicians who worked in the Merseyside factories. His organisational ability, personal prestige, experience of Lancashire and racial background made him the ideal person to deal with the absorption of West Indians to the Merseyside industrial and social scene. His cricketing fame was insufficient to prevent discrimination in other areas of his life. In 1944 he was the first Black person to successfully bring a court case against a service establishment that barred people on the grounds of colour. In 1943, he was given four days’ leave to captain the West Indies team against England at Lord’s. Prior to his arrival he was told by the Imperial Hotel there was no objection to his colour, so he paid a deposit, but when he arrived at the hotel it was made clear that he and his family were not welcome. Constantine brought an action against the Imperial hotel for breach of contract. He won his case against the Imperial Hotel in London for ‘failing to receive and lodge’ him and his family on grounds of colour. The judge who heard the case accepted without hesitation the evidence of Constantine, and rejected that given by the defendants. In the witness box, Constantine bore himself with modesty and dignity, dealt with all questions with intelligence and truth. He was awarded £5 in damages. This decision did not end the colour bar in British hotels – in 1946 two Sikh VCs were refused admission to a West End restaurant. Learie Constantine and CLR James wrote Colour Bar (1954) as an insider’s view of discrimination in Britain. Constantine continued to seek equal rights for people of colour in Britain from his earliest times in Britain. In 1963, along with other national figures such as Tony Benn and Harold Wilson, he spoke on the Bristol bus company colour bar dispute; the local bus company was boycotted until the ban on employing people of colour was rescinded. Constantine supported the sixty-day bus boycott that was led by local man Paul Stephenson. Constantine was a member of the League of Coloured Peoples – an organisation dedicated to fighting discrimination against people of colour – and later became its President.

Once he had retired as a first-class cricketer Learie Constantine worked for the BBC as a freelance commentator – an interest that he had commenced in the 1930s. He also wrote several books on cricket, including Cricket and I (1933), Cricket Crackers (1949) and The Young Cricketer’s Companion (1964). His non-cricket book was Colour Bar (1954) written about British ‘race’ relations from a Black perspective.

After working during the Second World War for the Ministry of Labour and National Service in Liverpool as a Welfare Officer responsible for West Indians employed in English factories, Constantine qualified as a barrister in 1954, while also establishing himself as a journalist and broadcaster. He returned to Trinidad in 1954, entered politics and became a founding member of the People’s National Movement, subsequently entering the Trinidad government as Minister of Communications, Works and Public Utilities. In 1962 he returned to England as Trinidad’s High Commissioner, serving until 1964. Constantine was granted a knighthood in 1962. He started his legal practice in 1964 when he was aged 63 years. In his final years, he served on the Race Relations Board, the Sports Council and the Board of Governors of the BBC. Failing health reduced his effectiveness in some of these roles, and he faced criticism for becoming a part of the British Establishment. Constantine was also appointed as the first black rector of the University of St Andrews in Fife in 1967. He was granted a life peerage in 1969 (Baron Constantine of Maraval and Nelson) – he became the first black man to be appointed to the House of Lords.

After working during the Second World War for the Ministry of Labour and National Service in Liverpool as a Welfare Officer responsible for West Indians employed in English factories, Constantine qualified as a barrister in 1954, while also establishing himself as a journalist and broadcaster. He returned to Trinidad in 1954, entered politics and became a founding member of the People’s National Movement, subsequently entering the Trinidad government as Minister of Communications, Works and Public Utilities. In 1962 he returned to England as Trinidad’s High Commissioner, serving until 1964. Constantine was granted a knighthood in 1962. He started his legal practice in 1964 when he was aged 63 years. In his final years, he served on the Race Relations Board, the Sports Council and the Board of Governors of the BBC. Failing health reduced his effectiveness in some of these roles, and he faced criticism for becoming a part of the British Establishment. Constantine was also appointed as the first black rector of the University of St Andrews in Fife in 1967. He was granted a life peerage in 1969 (Baron Constantine of Maraval and Nelson) – he became the first black man to be appointed to the House of Lords.

Learie Constantine succumbed to illness from lung disease and died of a heart attack on 1 July 1971, aged 69. He was buried in Trinidad in 1971 and he was posthumously awarded the country’s highest honour – The Trinity Cross; his wife Norma died two months after.

Source:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Learie_Constantine

http://www.100greatblackbritons.com/bios/lord_leary_constantine.html

http://historicalgeographies.blogspot.co.uk/2011/09/biography-learie-constantine.html