“Kwame Nkrumah was Africa’s magnificent dreamer. He dared to believe that African people could be masters of their destiny… He was the best example of dynamic African leadership to emerge in [the 20th] century.” ~Dr. John Henrik Clarke

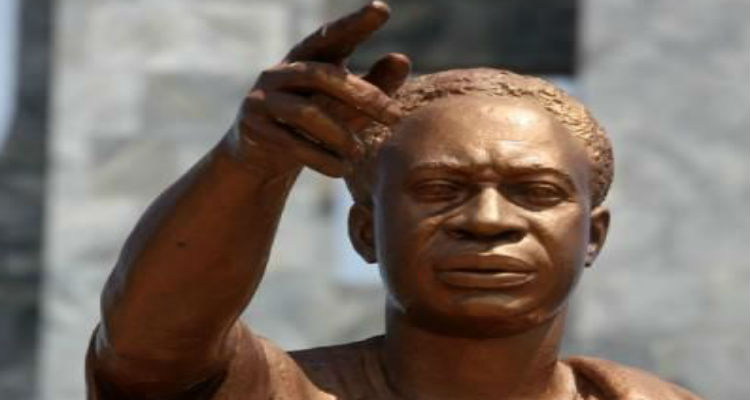

Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah was the prime minister and later president of Ghana, the first African country to gain freedom from European colonial oppression. An influential 20th-century advocate of Pan-Africanism, Nkrumah was Africa’s foremost spokesman and was a founding member of the Organization of African Unity. He was the winner of the Lenin Peace Prize in 1963.

Nkrumah was born Kwame Francis Nwia Kofie in the south-west of the Gold Coast on September 21, 1909. Although his mother, whose name was Nyanibah, later stated his year of birth was 1912, Nkrumah wrote that he was born on 18 September 1909, a Saturday, and by the naming customs of the Akan people was given the name Kwame, that being the name given to males born on a Saturday. During his years as a student in the United States, though, he was known as Francis Nwia Kofi Nkrumah, with Kofi being the name given to males born on Friday. The name of his father is not known; most accounts say he was a goldsmith. According to Ebenezer Obiri Addo in his study of the future president, the name “Nkrumah”, a name traditionally given to a ninth child, indicates that Kwame likely held that place in the house of his father, who had several wives. Kwame, though, was the only child of his mother.

Nkrumah’s mother sent him to the elementary school run by a Catholic mission at Half Assini, where he proved an adept student. He progressed through the ten-year elementary programme in only eight. By about 1925 he was a student-teacher in the school, and had been baptised into the faith. While at the school, he was noticed by the Reverend Alec Garden Fraser, principal of the Government Training College (soon to become Achimota School) in the Gold Coast’s capital, Accra. Fraser arranged for Nkumrah to train as a teacher at his school. Here, Columbia-educated deputy headmaster Kwegyir Aggrey exposed him to the ideas of Marcus Garvey and W. E. B. Du Bois. Aggrey, Fraser, and others at Achimota taught that there should be close co-operation between the races in governing the Gold Coast, but Nkrumah, echoing Garvey, soon came to believe that only when the black race governed itself could there be harmony between the races.

Nkrumah received his early education at the hands of Catholic missionaries. He went on to train as a teacher and for a few years taught elementary school in towns along the coast. He was popular and charismatic and earned a decent living. But exposure to politics and to a few influential figures sparked in him a greater interest — to go to America. He applied to universities in the United States, and with money raised from relatives, he set out on a steamer in 1935. By this time, Nkrumah was already the most radical of the young “Gold Coasters,” resenting deeply the exploitative aspects of colonialism. He reached New York almost penniless, and took refuge with fellow West Africans in Harlem. He then presented himself at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania and enrolled; a small scholarship and a campus job helped him make ends meet.

Founded before the Civil War, Lincoln University was America’s oldest black college, and its special atmosphere inspired and comforted Nkrumah. In the summers, he worked at physically demanding jobs — in shipyards and construction at sea. He studied theology as well as philosophy; he frequented the black churches in New York and Philadelphia and was sometimes asked to preach. He also forged ties with black American intellectuals, for whom Africa was becoming, in this time of political change, an area of extreme interest. It was during the years at Lincoln, and the ensuing ones as a graduate student in philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania, that he was to give substance to his anti-colonial feelings by studying, as he later wrote, “revolutionaries and their methods” (such as Lenin, Napoleon, Gandhi, Hitler, and, most important, Marcus Garvey, the Jamaican whose followers proclaimed him “provisional president of Africa”).

“Of all literature I studied, the book that did more than any other to fire my enthusiasm was Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey.”

Nkrumah’s formal political activity started in America but only began in earnest in London, where he went for further studies in 1945. While in England, he edited a pan-African journal, was vice president of the West African students’ union and helped organize the Fifth Pan-African Conference in Manchester. There, too, George Padmore, the important pan-Africanist, became his mentor and was a crucial influence until he died in 1959.

Nkrumah returned to his homeland in 1947 and became Secretary-General of the United Gold Coast Convention which was campaigning to end British rule. However, in 1948 he was expelled from the organization for leading a campaign of civil disobedience. He responded by founding the Convention People’s Party in 1949, the first mass political party in Africa.

Imprisoned by the British in 1950, he was released the next year after the CPP’s landslide election victory.

In 1952 Nkrumah became the country’s first prime minister. As Prime Minister, Nkrumah led an aggressive campaign for independence and achieved it in 1957.

On March 6, 1957 the Gold Coast became Ghana. Nkrumah declared:

“We are going to see that we create our own African personality and identity. We again rededicate ourselves in the struggle to emancipate other countries in Africa; for our independence is meaningless unless it is linked up with the total liberation of the African continent.”

Three years later he formed a new government, the Republic of Ghana. A devoted Pan-Africanist, Nkrumah forged alliances with both Guinea and Mali, and sought to create a league of African states with its own government. To help achieve this goal, in 1963 he and other African leaders formed the Organization of African Unity.

In February 1966, while Nkrumah was on a state visit to North Vietnam and China, his government was overthrown in a military coup led by Emmanuel Kwasi Kotoka and the National Liberation Council.

Nkrumah never returned to Ghana, but he continued to push for his vision of African unity. He lived in exile in Conakry, Guinea, as the guest of President Ahmed Sékou Touré, who made him honorary co-president of the country. He read, wrote, corresponded, gardened, and entertained guests. Despite retirement from public office, he felt that he was still threatened by western intelligence agencies. When his cook died mysteriously, he feared that someone would poison him, and began hoarding food in his room. He suspected that foreign agents were going through his mail, and lived in constant fear of abduction and assassination. In failing health, he flew to Bucharest, Romania, for medical treatment in August 1971. He died of prostate cancer in April 1972 at the age of 62.

Nkrumah was buried in a tomb in the village of his birth, Nkroful, Ghana. While the tomb remains in Nkroful, his remains were transferred to a large national memorial tomb and park in Accra.

“As far as I am concerned, I am in the knowledge that death can never extinguish the torch which i have lit in Ghana and Africa. Long after I am dead and gone, the light will continue to burn and be borne aloft, giving light and guidance to all people.”

Over his lifetime, Nkrumah was awarded honorary doctorates by Lincoln University, Moscow State University; Cairo University in Cairo, Egypt; Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland; Humboldt University in East Berlin; and many other universities.

In 2000, he was voted Africa’s “Man of the Millennium” by listeners to the BBC World Service, being described by the BBC as a “Hero of Independence,” and an “International symbol of freedom as the leader of the first African country to shake off the chains of colonial rule.”

In September 2009, President John Atta Mills declared 21 September (the 100th anniversary of Kwame Nkrumah’s birth) to be Founder’s Day, a statutory holiday in Ghana to celebrate the legacy of Kwame Nkrumah.

Sources:

http://www.blackpast.org/gah-nkrumah-kwame-1909-1972#sthash.WqoPxgH3.dpuf

http://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/people/person.php?ID=177

http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/people/highlights/000914_nkrumah.shtml

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kwame_Nkrumah