“Everyone has a gift for something, even if it is the gift of being a good friend.”

Marian Anderson was one of the most celebrated singers of the twentieth century. Anderson was the first African-American woman to ever perform at the White House and the first African-American to sing with New York’s Metropolitan Opera. She worked for several years as a delegate to the United Nations Human Rights Committee and as a “goodwill ambassadress” for the United States Department of State, giving concerts all over the world. She participated in the civil rights movement in the 1960s, singing at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. The recipient of numerous awards and honors, Anderson was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1963, the Kennedy Center Honors in 1978, the National Medal of Arts in 1986, and a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1991.

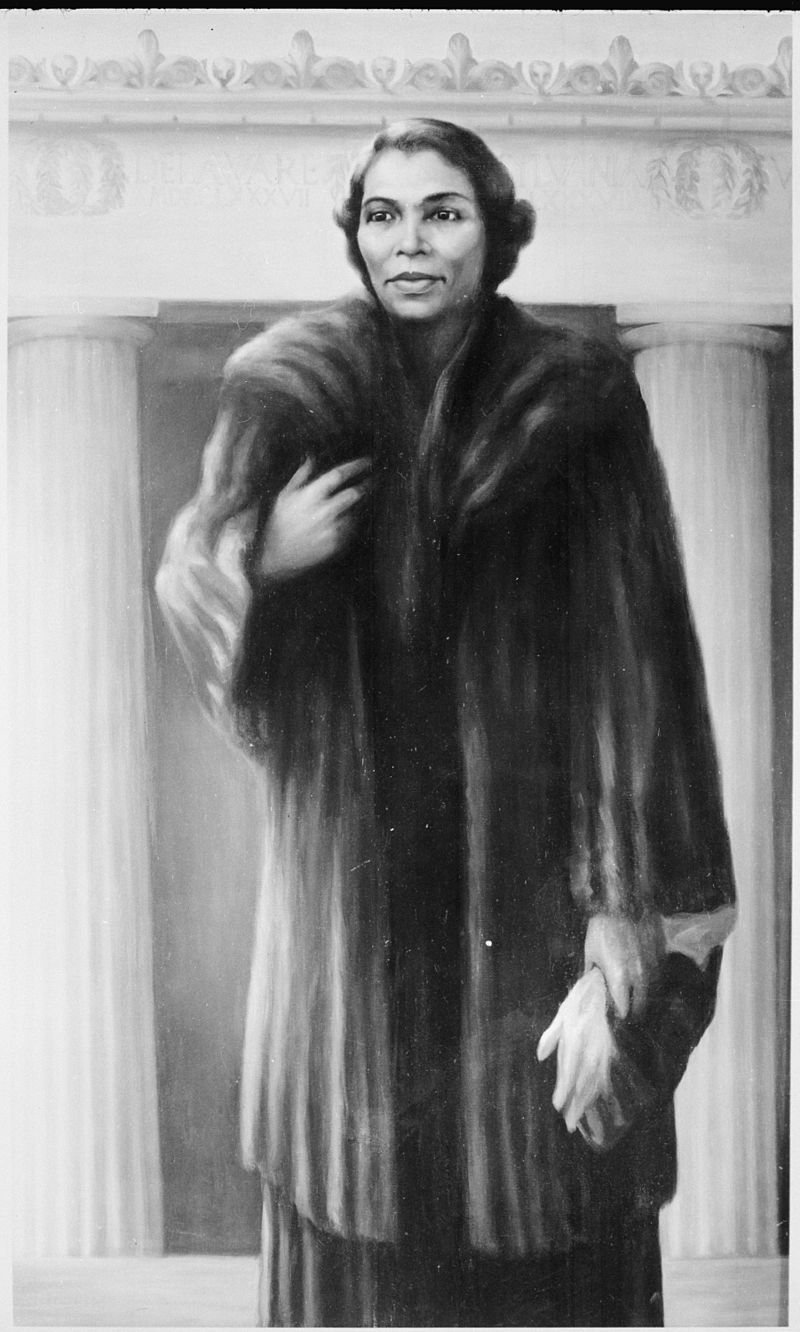

Marian Anderson’s painting by Betsy Graves Reyneau

Marian Anderson was born on February 27, 1897, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Her mother, Annie Delilah Rucker, was a former schoolteacher and her father, John Berkley Anderson, was a coal and ice dealer. The oldest of three girls, Anderson was just 6 years old when she earned the nickname “Baby Contralto.” Anderson’s parents were both devout Christians and the whole family was active in the Union Baptist Church in South Philadelphia. Marian’s Aunt Mary (John Berkley’s sister) was particularly active in the church’s musical life and, noticing her niece’s talent, convinced her to join the junior church choir at the age of six. In that role, she got to perform solos and duets, often with her Aunt Mary. She was also taken by her aunt to concerts at local churches, the YMCA, benefit concerts, and other community music events throughout the city. Marian credited her aunt’s influence as the reason she pursued a singing career. Beginning as young as six, her aunt arranged for Marian to sing for local functions where she was often paid 25 or 50 cents for singing a few songs. When she was eight, her father bought her a piano. With the family unable to afford lessons, the prodigious Anderson taught herself how to play the piano. As she got into her early teens, Marian began to make as much as four or five dollars for singing; a considerable amount of money for the early 20th century. At the age of 10, Marian joined the People’s Chorus under the direction of singer Emma Azalia Hackley, where she was often given solos.

When Marian was 12, her father was accidentally struck on the head while at work at the Reading Terminal, just a few weeks before Christmas of 1909. He died of heart failure a month later at age 34. Anderson and her family moved into the home of her father’s parents, Grandpa Benjamin and Grandma Isabella Anderson. When she was only 14, the choirmaster, Alexander Robinson, moved her from the youth to the adult choir. She stunned the other members not only with the strength and beauty of her voice but also with her ability to sing any part of a hymn upon demand. Whether it was the soprano, alto, tenor, or bass part that Robinson needed, he could rely on Marian to provide it.

The congregation had such faith in her that they started a “Marian Anderson’s Future Fund,” which would pay for lessons with the city’s leading voice instructors and support her performances. During the next several years she was coached by soprano Mary Saunders Patterson and contralto Agnes Reifsnyder. She gave concerts while she attended the South Philadelphia High School for Girls, and her teacher, Dr. Lucy Langdon Wilson, arranged for the famed Italian voice master, Giuseppe Boghetti, to hear her. He remembers this first meeting as occurring “at the end of a long hard day, when I was weary of singing and singers, and when a tall calm girl poured out ‘Deep River’ in the twilight and made me cry.”

Sometimes racial prejudice is like a hair across your cheek. You can’t see it, you can’t find it with your fingers, but you keep brushing it because the feel of it is irritating.

After high school, Marian applied to an all-whyte music school, the Philadelphia Music Academy (now University of the Arts), but was turned away because of its racist policy. The woman working the admissions counter replied, “We don’t take colored” when she tried to apply. Undaunted, Marian pursued studies privately with Boghetti through the continued support of the Philadelphia Black community.

In 1925 Boghetti entered Marian in a contest with 300 other contestants. The winner would make a solo appearance with the New York Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra. Seventeen-year-old Marian auditioned and won. The achievement prompted Boghetti to take her to Europe. Marian made her European debut at the Paris Opera House in 1935. The success she met with there made her the toast of Europe, entertaining in command performances before King Gustav in Stockholm and King Christian in Copenhagen. As a young Black woman from South Philadelphia who could superbly deliver Russian folk songs, classic German and French arias as well as Black Spirituals, she was a wonder and people flocked to hear her. Sibelius, the Finnish composer, was so inspired that he dedicated the song, “Solitude,” to her.

The success she encountered in Europe brought her back to America in 1935 for a public debut at Carnegie Hall in New York. The day before the performance, while still on the Ile de France, Marian fell and broke her ankle. Determined to make her appearance, she performed the entire program standing on one foot, balancing against the piano, with her floor-length gown covering the cast on her ankle. Again, she met with success. It won her so much exposure and popularity that in 1936 she became the first African American to be invited to perform at the White House and then sang there again when Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt were entertaining the King and Queen of Great Britain in 1939.

Despite the fact that she was the country’s third-highest concert box office draw, Marian was still subject to the racial bias of the time. When she traveled in the United States, she was often, like all African Americans of her time, restricted to “colored” waiting rooms, hotels, and train cars. In one instance, she was allowed to stay in an upscale Los Angeles hotel, but not to enter its formal dining room. She learned to avoid these affronts by staying with friends in the cities where she performed and driving her own car instead of taking the train. When she performed in the South, despite a general acceptance by the public, the newspapers could not bring themselves to refer to her as “Miss Anderson.” The Southern press came up with other forms of address in order to avoid paying her any type of deference; “Artist Anderson” and “Singer Anderson” frequently being used.

Despite her success, not all of America was ready to receive her talent. In 1939 her manager tried to set up a performance for her at Washington, D.C.’s Constitution Hall. But the owners of the hall, the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) informed Marian and her manager that no dates were available. However, the real reason for turning Anderson away lay in a policy put in place by the DAR that committed the hall to being a place strictly for whyte performers. The rebuff was widely publicized when Eleanor Roosevelt, herself a member of the DAR, publicly resigned from the organization in protest. In her letter to the DAR, she wrote, “I am in complete disagreement with the attitude taken in refusing Constitution Hall to a great artist… You had an opportunity to lead in an enlightened way and it seems to me that your organization has failed.”

In response, Eleanor and the Committee arranged for Marian to give her concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial with the Mall of Washington as her auditorium. Her groundbreaking performance took place in front of a crowd of more than 75,000, which was broadcast live for millions of radio listeners. Overwhelmed by the occasion, Marian was tearful when she delivered “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen” and “America” with heart-breaking pathos. The event was so momentous and inspiring that the DAR finally invited Anderson to sing at the Hall in 1943 for a war relief concert.

Over the next several decades of her life, Marian’s stature only grew. In 1961 she performed the national anthem at President John F. Kennedy’s inauguration. Two years later, Kennedy honored the singer with the Presidential Medal of Freedom. A key moment in her career came in 1955 when she became the first African American to perform at the Metropolitan Opera. Three years after this immense achievement President Eisenhower named her a delegate to the 13th General Assembly of the United Nations.

In 1965 Marian gave her final performance at Carnegie Hall in New York. On April 8, 1993, she died in Portland, Oregon at the home of her nephew, conductor James DePriest.

In 1965 Marian gave her final performance at Carnegie Hall in New York. On April 8, 1993, she died in Portland, Oregon at the home of her nephew, conductor James DePriest.

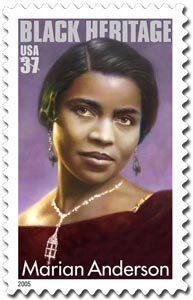

Marian Anderson had over 1,500 songs in her repertoire, sang in nine languages, and performed on four continents. She received national honors throughout her life including: the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal in 1939; the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1963; the United Nations Peace Prize in 1977; and a Grammy Award for Lifetime Achievement in 1991. Over two dozen universities presented her with honorary doctorates. In 1980, the United States Treasury coined a half-ounce gold medal with her likeness, and in 2005 a commemorative postage stamp was issued in her honor as part of the “Black Heritage” series.

Source:

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/biography/eleanor-anderson/

http://www.biography.com/people/marian-anderson-9184422

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marian_Anderson