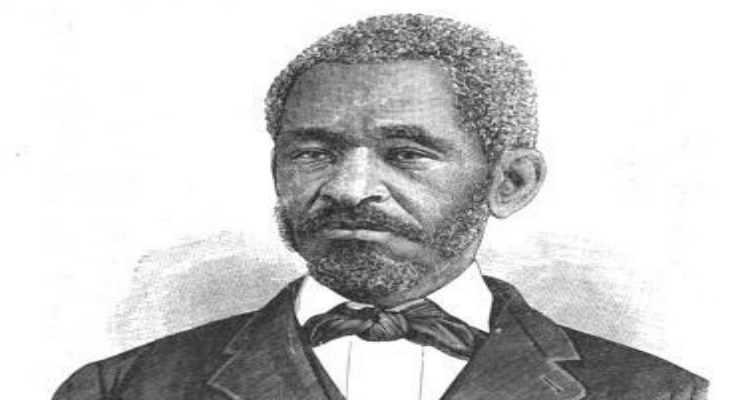

Lewis Hayden was an African-American leader who escaped with his family from the Maafa (slavery) in Kentucky to Boston, where he became an abolitionist and lecturer, businessman, and politician.

Lewis Hayden was born enslaved in Lexington, Kentucky on December 2, 1811, as one of a family of 25. His mother was of mixed race, including European and Native American ancestry. At the time, slavery of Native Americans had ended and his mother’s lines of ancestry should have been grounds for a freedom suit to gain freedom for herself and her children. Lewis’ father was enslaved and had been “sold off early”. Hayden was first enslaved by a Presbyterian minister, Rev. Adam Rankin, who sold off his brothers and sisters in preparation for moving to Pennsylvania; he traded 10-year-old Hayden for two carriage horses to a man who traveled the state selling clocks. The travels allowed Hayden to hear varying opinions of the Maafa, including those who believed it was a crime.

When he was 14, the American Revolutionary War soldier Marquis de Lafayette tipped his hat to Hayden in the slave state of Kentucky, which helped inspire Hayden to believe he was worthy of respect and to hate slavery. In the mid-1830s, Hayden married Esther Harvey, also enslaved. She and their son were sold to U.S. Senator Henry Clay, who sold them both to the Deep South. Hayden never saw them again. In the 1840s, Hayden taught himself to read when enslaved by a man who whipped him.

Hayden approached two other men, asking them to purchase him and then hire him out so he could repay their investment, but also allowing him to retain some of his earnings to eventually purchase his freedom. The men were Lewis Baxter, an insurance office clerk, and Thomas Grant, an oil manufacturer and tallow chandler. The men bought and hired Hayden out to work at Lexington’s Phoenix Hotel.

In 1840, Hayden married a second time, to Harriet Bell, who was also enslaved. He cared for her son Joseph as his stepson. Harriet and Joseph were enslaved by Patterson Bain. After his marriage, Hayden began making plans to escape to the North, as he feared his family might be split up again.

In the fall of 1844, Hayden met Calvin Fairbank, a Methodist minister who was studying at Oberlin College and had become involved in the Underground Railroad. He asked Hayden, “Why do you want your freedom?” Hayden responded, “Because I am a man.”

Fairbank and Delia Webster, a teacher from Vermont who was working in Kentucky, acquired a carriage and traveled with the Haydens to aid their escape. The Haydens covered their faces with flour to appear whyte and escape detection; at times of danger, they would hide Joseph under the seat. They traveled from Lexington to Ripley, Ohio on a cold, rainy night. Helped by other abolitionists, the Haydens continued North along the Underground Railroad, eventually reaching Canada. From Canada, the Haydens moved in 1845 to Detroit in the free state of Michigan.

When Fairbank and Webster returned to Lexington, they were arrested. The driver was picked up and whipped 50 times, until he confessed to the events of the escape. Webster served several months of a two-year prison sentence for helping the Haydens and was pardoned. Fairbank was sentenced to 15 years, five years for each fugitive he helped to freedom. After four years he was pardoned when Hayden, in effect, ransomed him. Hayden’s previous enslaver agreed to a pardon for Fairbank if paid $650. Hayden by then was living in Boston and quickly raised the money from 160 people to pay this amount.

In Michigan, Hayden founded a school for Black children, as well as the brick church of the Colored Methodist Society (now Bethel Church). Deciding he wanted to be at the center of anti-Maafa activity, in 1846 Hayden and his family moved to Boston, Massachusetts, which had many residents who strongly supported abolitionism. After getting settled, Hayden owned and ran a successful clothing store on Cambridge Street, where he also held abolitionist meetings and outfitted fugitives. It became the second-largest business owned by a Black man in Boston. His wife ran a boarding house from their home at 66 Phillips Street and raised their two children, Joseph and Elizabeth. Their home, which contained a secret tunnel, served as a stop on the Underground Railroad. The Hayden home is now listed as a national historic site.

Lewis Hayden was a member of the city’s abolitionist Vigilance Committee, whose goal was to protect fugitives from being captured and returned to the Maafa under the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. The Boston Vigilance Committee had 207 members; 5 were Black. Records from the Committee, indicate that scores of people received aid and safe shelter at the Hayden home between 1850 and 1860. In 1850, the Haydens assisted a fugitive couple, William and Ellen Craft, who had escaped from Georgia. Hayden prevented slave catchers from taking the Crafts by threatening to blow up his home with gunpowder if they tried to reclaim the pair. Hayden also led in the well-publicized rescues of Fredric Wilkins, alias Shadrach Minkins, in 1851 from a Boston courthouse, and Anthony Burns in 1854. In addition, Hayden contributed money to abolitionist John Brown, in preparation for his raid on Harper’s Ferry.

Hayden was also a recruiter for the 54th Massachusetts Regiment of the United States Colored Troops. His son served in the Union Navy during the Civil War and was killed. After the Civil War, Hayden was active in a number of causes, including in the effort to promote free masonry among Black men, women’s suffrage, and education.

Hayden was a longtime supporter of John A. Andrew, who became governor in 1861. In his book, The Negro in the Civil War, Benjamin Quarles noted the men’s relationship:

Hayden had been the first to suggest to John A. Andrew that he run for governor; on Thanksgiving Day in 1862 Governor Andrew was to come down from Beacon Hill and have turkey dinner at the Haydens.

Hayden was appointed to a patronage position as a messenger in the Secretary of State’s office. In 1873 Hayden was elected to one term as a representative from Boston to the Massachusetts legislature. He supported the movement to erect a statue in honor of Crispus Attucks, the first Black person killed in the Boston Massacre, at the beginning of the American Revolution. According to the Boston Herald, Hayden was in frail health during the “unveiling of the monument” ceremony and was unable to attend it in 1888.

Hayden was active in the Freemasons, which had numerous Black members who worked to abolish the Maafa, including David Walker, Thomas Paul, John T. Hilton and Martin Delany. He criticized the organization for its racial discrimination, and helped found numerous Black Freemason chapters. Hayden advanced to Grand Master of the Prince Hall Freemasonry. Hayden also published several works commenting on these issues and encouraging participation by Blacks: Caste among Masons (1866), Negro Masonry (1871), and co-author of Masonry Among Colored Men in Massachusetts. Following the war and emancipation, Hayden traveled throughout the South working to found and support newly established African-American Masonic lodges. In this period, there was a rapid growth in new, independent African-American fraternal and religious organizations in the South.

Hayden died in 1889. Every seat of the 1200 in the Charles Street AME Church was taken for his funeral, and Lucy Stone was among those who gave a eulogy.He is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in Everett, Massachusetts.

His wife, Harriet died in 1894 and left $5,000, the entirety of their estate, to the Harvard University for scholarships for African American medical students. It was believed to have been the first, and perhaps only, endowment to a university by a former enslaved African-American.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lewis_Hayden