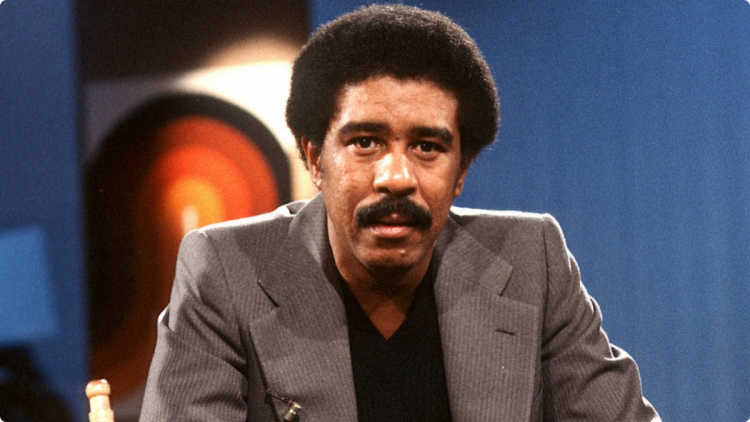

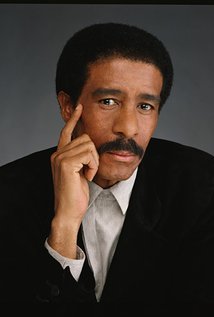

Richard Pryor was one of the most influential stand-up comedians of his generation, and starred in a number of hit films and comedy recordings. He created a new type of humor, one that blended self-effacing statements about being African American with sharp political insights.

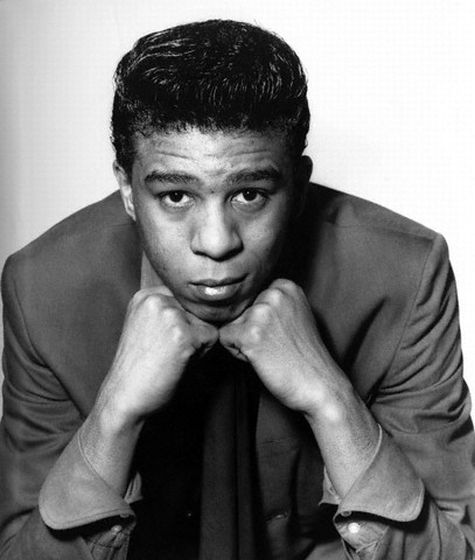

Richard Pryor was born on December 1, 1940 in Peoria, Illinois to LeRoy Pryor, Jr. (also known as Buck Carter) and Gertrude Thomas. A tough, streetwise kid, Pryor’s father won a Golden Gloves tournament in Chicago at the age of 18. One of four children raised in his grandmother’s brothel, his mother worked as a prostitute and bookkeeper. Both parents were violent and alcoholic.

Richard experienced rape at the age of six (by a teenaged neighbor) and molestation by a Catholic priest during catechism. He watched his mother perform sexual acts with Peoria’s mayor. One way the young boy escaped from these traumatic experiences was to attend the movies. Seated in the “black seats” at his local cinema, Pryor consumed the screen worlds of such heroes as John Ford and Howard Hawks, stirring within a wild ambition to become a star like them. He was expelled from school for a petty offense at age 14, and began working as janitor at a local strip club, work as shoe-shine and “careers” as drummer, meat packer, truck driver, and billiard hall attendant combined to pre-ordain a perspective of the black underclass in 1950s America that Pryor translated into honest and hilarious routines.

Several brushes with the country’s penal system gave him first-hand knowledge of the treatment of blacks within it. Ask anyone who has followed Pryor’s comedy and the word authentic comes up. But, as the Grateful Dead sang, “What a long, strange road it’s been” for the 65 years that Pryor blessed this earth. And, as Richard says, “I ain’t dead yet, Muther Fucka!”

Pryor’s youth was spent in a house of prostitution run by his grandmother, Marie Carter. His mother often disappeared for months at a time, and finally abandoned him when he was ten. His father rarely saw him. Therefore, Pryor’s grandmother was his sole means of support as a child. She was strict and beat him when he misbehaved. Pryor frequented pool halls and was often in trouble. He was also the victim of physical and sexual abuse. When he was six, he was molested by a teenage pedophile named “Bubba,” who, many years later, brought his own son to Pryor for an autograph. Rather than dwelling on his anger over the incident, Pryor worried that the pedophile’s son was being subjected to abuse.

Pryor’s first introduction to a life of performing came at age 12 when Juliette Whittaker, a supervisor at a public recreational facility in Peoria, cast him in a local production of Rumplestiltskin. Whittaker was so impressed by Richard’s comic ability that she arranged talent shows to showcase him and continued to influence him throughout his career.

While serving in the Army (a brief stint 1958 to 1960 that ended when he had an altercation with a fellow G.I.), Pryor performed in many amateur shows. Upon his discharge, he got his first cabaret gig at his hometown Harold’s Club, where he played piano and sang badly.

Quickly realizing that audiences preferred his jokes to his singing, Pryor began working as a professional comic in clubs throughout the Midwest. Inspired by Bill Cosby, Pryor went to New York in 1963 and gained recognition for his club work as a stand-up, performing on the same bill as such famous personalities as Bob Dylan and Richie Havens. While in New York, Pryor also garnered some mentorship from none other than the great Woody Allen.

In 1966, Pryor penetrated the medium of television, appearing in summer shows such as Rudy Vallee’s On Broadway Tonight and the Kraft Summer Music Hall. These appearances, as well as several on the Ed Sullivan Show, and the Johnny Carson and Merv Griffin shows brought Las Vegas calling.

His first foray into Las Vegas was as the opening act for Bobby Darin at the prestigious Flamingo Hotel. But hipper and more controversial than Cosby and the other Vegas acts, Pryor found it difficult to conform to the constrained Vegas format and finally walked off stage during a show at the Aladdin in 1969. On a journey to hone his voice, Pryor moved to Berkeley, California and hung out with such counter-cultural writers and personalities as Ishmael Reed and Huey P. Newton. After a couple of years in Berkeley, Pryor hit Hollywood in touch with his very unique brand of comedy.

He turned to films, starring in The Busy Body with Sid Caesar, and the classic Wild in the Streets, and released his first album, Richard Pryor. More movies followed, including Lady Sings the Blues, which earned him strong notice as Billie Holliday’s drug-addicted piano player. In all, Pryor, who in 1980 formed his own production company, Indigo (under the banner of Columbia Pictures), appeared in almost 50 movies, including several with Gene Wilder and the autobiographical Jo Jo Dancer, Your Life is Calling. Years before Eddie Murphy became the Klumps, Pryor took on three roles in the movie Which Way Is Up, appearing as a young man and his father as well as the wayward minister Lennox Thomas.

In 1983, Pryor was paid $4 million (a unprecedented amount for a black actor and a million more than the film’s star Christopher Reeve) for his role as accomplice to the villain in Superman III. For the most part, Pryor considers his films undistinguished products from the Hollywood assembly-line, but amongst the formulaic slop there are black pearls of comedy that testify to his genius.

On television, Pryor headlined and received high accolades for two series: The Richard Pryor Show (NBC, 1977), which contained one of the most talked about show openings in the history of television, and the children’s show Pryor’s Place (1984). He also hosted the hottest show on American TV, Saturday Night Live, with fellow comic luminaries as Dan Ackroyd, Chevy Chase and John Belushi. After appearing in both dramatic and comedic roles in dozens of popular television shows, in 1991 Pryor was the subject of a well-received variety special A Party for Richard Pryor. His work also earned him such honors as NATO Entertainer of the Year Award (National Association of Theater Owners, 1982), Lifetime Achievement Honoree for the American Comedy Awards (1992), CableACE Best Entertainment/Cultural Documentary or Informational Special (1993) and the NAACP Hall of Fame Award (1996).

But starring on television was not enough for this versatile entertainer and he began writing for shows as well, among them Sanford and Son and The Flip Wilson Show and most notably two 1973 Lily Tomlin specials, one of which earned him both an Emmy and a Writers Guild Award. At the same time, Pryor earned recognition for his directing abilities. His first screenwriting attempt (with Mel Brooks), Blazing Saddles, continued his success in this arena by earning him the Writers Guild of America Award for Best Comedy Written Directly for the Screen.

Pryor also tried his hand at authorship, penning (with Todd Gold) the autobiography Pryor Convictions: And Other Life Sentences which Pantheon Books published to widespread acclaim in 1995.

In 1998, Pryor received the first Mark Twain Prize in celebration of American humor in a ceremony at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C. Over 2,000 guests, including Whoopi Goldberg, Robin Williams, Chris Rock, Morgan Freeman, Richard Belzer, Tim Allen, and Damon Wayans, attended the ceremony. The ceremony featured video clips of some of Pryor’s most famous comedic moments interspersed with comments and tributes from comedians and actors who were influenced by Pryor. Although he was unable to rise from his chair, Pryor graciously accepted the award with a whispered “Thank you.” In a written statement that was quoted in Jet, Pryor wrote: “I feel great about accepting this prize. It is nice to be regarded on par with a great white man—now that’s funny. Seriously, though, two things people throughout history have had in common are hatred and humor. I am proud that, like Mark Twain, I have been able to use humor to lessen people’s hatred!”

In the years that followed, Pryor was universally acclaimed for his contributions to American humor. Handelman noted: “Even though his best work had nothing to do with one-liners, Pryor [was] unquestionably still the most important and influential stand-up comedian of the past 25 years. Using raw street language, he [turned] black American life into breathtaking one-man theater, his rubbery face, multioctave voice, and lithe body physicalizing every situation.” As Damon Wayans told Jet, “If [a comedian] hasn’t copied from Richard Pryor, then you’re probably not funny. Like Michael Jordan has defined the game of basketball, Richard Pryor has defined stand up comedy.” Pryor finally succumbed to a heart attack on December 10, 2005, at his home in Northridge, California.

Sources:

http://richardpryor.com/biography.php

http://biography.yourdictionary.com/richard-pryor#q3vw4z8IPZOu8cUp.99