“I have created nothing really beautiful, really lasting, but if I can inspire one of these youngsters to develop the talent I know they possess, then my monument will be in their work.”

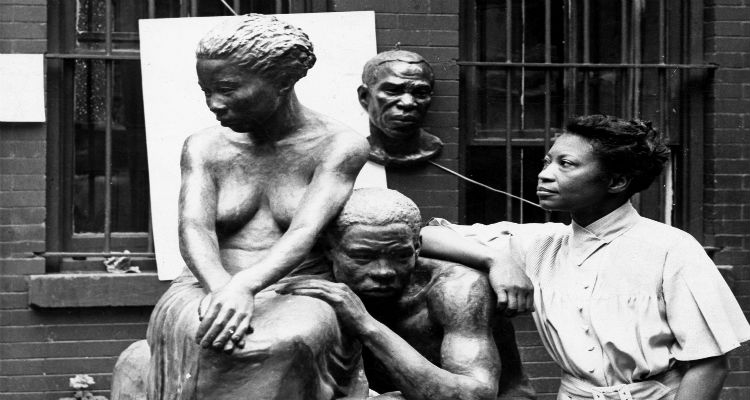

Augusta Savage was an acclaimed sculptor who was also one of the leading artists of the Harlem Renaissance, as well as an influential activist and arts educator. Savage began creating art as a child by using the natural clay found in her hometown. After attending Cooper Union in New York City, she made a name for herself as a sculptor during the Harlem Renaissance and was awarded fellowships to study abroad. Savage later helped found the Harlem Artists’ Guild and served as a director for the Harlem Community Center.

Augusta Savage was born Augusta Christine Fells on February 29, 1892, in Green Cove Springs, Florida. As one of 13 children in a poor family, Savage spent many hours playing in the mud outside her Florida home, learning to model figures out of the red earth. Although she showed exceptional talent at a young age, Savage’s father, a Methodist minister, discouraged his daughter’s growing passion and would beat her when he found her sculptures. This was because at that time, he believed her art to be a sinful practice, based upon his interpretation of the “graven images” portion of the Bible. After the family moved to West Palm Beach, she sculpted a Virgin Mary figure, and upon seeing it, her father changed his mind, regretting his past actions.

In West Palm Beach, Savage entered a group of figures into a competition at a local county fair and won a prize. This small recognition launched her art career. Soon, she was teaching sculpture classes at the local high school and selling small pieces to affluent members of the community. Also in 1907, at age 15, she married John T. Moore and gave birth to a daughter, Irene, the following year. Unfortunately, Moore died soon after the birth of his daughter.

Widowed at an early age, Savage moved back in with her parents, who raised Irene with her. She continued to model clay and applied for a booth at the Palm Beach county fair. The initially apprehensive fair officials ended up awarding her a US$25 prize, and the sales of her art totaled US$175; a significant sum at that time and place. In 1915, she left her family and moved to Jacksonville with the intention of making a living as a sculptor. She soon married again, this time to James Savage, a local carpenter. On learning that the South would not support her as a Black artist, and simultaneously became increasingly unhappy in her second marriage, she moved back to New York City in 1921 after divorcing her husband, leaving her daughter in the care of her parents.

Savage arrived in New York with only five dollars in her pocket. However, she quickly found a job and an apartment and registered for classes at Cooper Union. Excelling in her art classes at Cooper, she was accelerated through foundation classes, as her talent and ability were impressive. The staff and faculty at Cooper awarded her funds for tuition and room & board.

In 1923, Savage applied for a summer art program sponsored by the French government; although being more than qualified, she was turned down by the international judging committee, solely because of racial prejudice. Deeply upset, she questioned the committee, beginning the first of many public fights for equal rights in her life. The incident got press coverage on both sides of the Atlantic, and eventually the sole supportive committee member, sculptor Hermon Atkins MacNeil—who at one time had shared a studio with Henry Ossawa Tanner—invited her to study with him.

Also, in 1923, she married for a third time, to Robert Poston, an activist and colleague of Marcus Garvey. Although the match was a happy one, Poston died suddenly on a boat returning from Africa five months after their wedding. Widowed once more, Savage found herself struggling to support both her aging parents and daughter, who had moved into her small West 137th Street apartment in Florida. Her father had been paralyzed by a stroke, and the family’s home destroyed by a hurricane. She was forced to worked in Manhattan steam laundries to support herself and her family, while she continued to work on her art at night. During this time she obtained her first commission, for a bust of W.E.B. Du Bois for the Harlem Library. Her outstanding sculpture brought more commissions, including one for a bust of Marcus Garvey. Her bust of William Pickens Sr., a key figure in the NAACP, earned praise for depicting an African-American in a more humane, neutral way as opposed to stereotypes of the time, as did many of her works.

In 1925, Savage won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Rome; the scholarship covered only tuition, however, and she was not able to raise money for travel and living expenses. Thus she was unable to attend. Knowledge of Savage’s talent and struggles became widespread in the African-American community; fund-raising parties were held in Harlem and Greenwich Village, and African-American women’s groups and teachers from Florida A&M all sent her money for studies abroad.

In 1929, with assistance from the Julius Rosenwald Fund, Savage enrolled and attended the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, a leading Paris art school. Other artists in her Harlem community came together to raise additional funds to support her travel to Europe. In Paris, she studied with the sculptor Charles Despiau. She exhibited and won awards in two Salons and one Exposition. She toured France, Belgium, and Germany, researching sculpture in cathedrals and museums. The two years that Savage spent in Rome proved to be the most productive of her career. Her work was praised by European critics and she participated in numerous important exhibitions.

When Savage returned from Europe in late 1931, the Great Depression had gripped America and had almost stopped art sales. However, in 1934 she became the first African-American artist to be elected to the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors. She established the Savage Studio of Art and Crafts in Harlem, offering classes for both children and adults throughout the 1930s. Savage became known as a teacher who was both inspirational and demanding and had as her students many of Harlem’s rising artists including Jacob Lawrence, Norman Lewis, and Gwendolyn Knight. In 1939, she opened her own gallery, The Salon of Contemporary Negro Art, in order to more directly assist emerging African American artists.

While struggling to get the gallery off the ground, she also completed her final public commission. Four artists had been asked to make pieces for the 1939 New York World’s Fair, and Savage was the only woman in the group. Her piece, Lift Every Voice and Sing, depicted a harp on which the strings were replaced with singing children. Although the piece drew large crowds at the Fair, like many of Savage’s other works, it was never cast in bronze and the original plaster sculpture was eventually destroyed.

In 1945, Savage retired from the art world. She taught art to children and wrote children’s stories. Her school evolved into the Harlem Community Art Center; 1500 people of all ages and abilities participated in her workshops, learning from her multi-cultural staff, and showing work around New York City.

However, in the late 1940s, exhausted and worn down from her teaching and community activism, and deeply depressed by the financial struggle, Savage left Harlem for a small farm in upstate New York, where she stayed until 1960. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2001 as the Augusta Savage House and Studio. She choose to spend her time working on small sculptures and holding art classes for local children. She never exhibited her work again but continued to teach until her death from cancer on March 26, 1962.

Much of Savage’s work was in clay or plaster, as she could not often afford bronze. One of her most famous busts is titled Gamin, which is on permanent display at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.; a life-sized version is in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

The Augusta Fells Savage Institute of Visual Arts, a Baltimore, Maryland public high school, is named in her honor.

In 2007 the City of Green Cove Springs, Florida nominated her to be inducted into the Florida Artist Hall of Fame; she was inducted the spring of 2008. Today, at the actual location of her birth there is a Community Center named in her honor.

Source:

https://blackhistorynow.com/augusta-savage

https://zocalopoets.com/2014/02/10/lift-every-voice-and-sing-augusta-savage-the-harp

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Augusta_Savage