[dropcap size=small]W[/dropcap]illiam Harvey Carney was an African American soldier during the American Civil War who received the Medal of Honor for his actions during the Battle of Fort Wagner.

Carney’s actions at Fort Wagner preceded those of any other black recipient but he was not presented with the honor until nearly 37 years later. He was the 21st African-American to be awarded the Medal, the first recipient having been Robert Blake, in 1864.

Carney was born enslaved on February 29, 1840, at Norfolk, VA. His father, also named William, escaped the Maafa (slavery), reaching freedom through the underground railroad. William Sr. then worked hard to buy the freedom of the rest of his family. The free and reunited family settled in New Bedford in the second half of the 1850s. Young William learned to read and write, and by age 15 he was interested in becoming a minister.

He gave up his pursuit of the ministry, however, to join the Army. In an 1863 edition of the Abolitionist newspaper The Liberator, Carney stated: “Previous to the formation of colored troops, I had a strong inclination to prepare myself for the ministry; but when the country called for all persons, I could best serve my God serving my country and my oppressed brothers. The sequel in short—I enlisted for the war.”

He became a member of, and trained with, the 54th Massachusetts Colored Infantry’s C Company. Most of the soldiers in the unit were conscientious and focused on the task at hand. Union General Ullman later said of the men in the all-black units, “They are far more earnest than we…They know the deep stake they have in the issue.”

The assault on Fort Wagner would be the first real test of these young black, Union soldiers–every one of them a volunteer. Though the 54th Massachusetts was federalized, it was an entirely separate regiment. Despite Lincoln’s Proclamation and widening acceptance of these “soldiers of color”, some prejudices and preconceived notions still prevailed…even in the North. So it was that the brave but un-battle-tested young men of the 54th found themselves lying in the sand, waiting for the order to lead the advance on Fort Wagner. Among those brave soldiers was 23-year old Sergeant William Carney.

As evening began to fall the order came. The brave young men jumped to their feet and charged at a run towards the enemy stronghold. The Confederate defenders were prepared for them and cannon fire and bullets flew through the air, devastating the advancing 54th. Heedless of the danger and often fighting hand to hand, the 54th continued the advance. Ahead of them Sergeant John Wall carried the colors, the red, white and blue of the United States of America. Suddenly a rifle bullet dropped Sergeant Wall and the flag began to fall to the ground. Sergeant William Carney threw his rifle aside and grasped the colors before they touched the ground. He soon found himself alone, on the fort’s wall, with bodies of dead and wounded comrades all around him. He knelt down to gather himself for action, still firmly holding the flag while bullets and shell fragments peppered the sand around him.

Carney surveyed the battlefield and noticed that other Union regiments had attacked to his right, drawing away the focal point of the Rebel resistance. To his left he saw a large force of soldiers advancing down the ramparts of the fort. At first he thought they might be were Union forces. Flashes of musketry soon doomed his hopes. The oncoming troops were Confederates.

He wound the colors around the flagpole, made his way to a low protective wall and moved along it to a ditch. When Carney had passed over the ditch on his way to the fort, it was dry. But now it was waist deep with water.

He seemed to be alone, surrounded by the wreckage of his regiment. Carney wanted to help the wounded, but enemy fire pinned him down. Crouching in the water, he figured his best chance was to plot a course back to Federal lines and make a break for it.

Carney rose to get a better look. It was a fateful move. As he later wrote: “The bullet I now carry in my body came whizzing like a mosquito, and I was shot. Not being prostrated by the shot, I continued my course, yet had not gone far before I was struck by a second shot.”

Despite carrying two slugs in his body, Carney kept moving. Shortly after being hit the second time he saw another Union soldier coming in his direction. When they were within earshot, Carney hailed him, asking who he was. The Yank replied he was with the 100th New York, and asked if Carney was wounded. Carney said he had indeed been shot, and then flinched as a third shot grazed his arm. The 100th soldier came to his aid and helped him move farther to the rear. “Now then,” said the New York soldier, “let me take the colors and carry them for you.” Carney, though, would not consent to that, no matter how battered he was. He explained that he would not be willing to give the colors to anyone who was not a member of the 54th Massachusetts.

The pair struggled on. They did not get far before yet another bullet hit Carney, grazing him in the head. The two men finally managed to stumble to their own lines. Carney was taken to the rear and turned over to medical personnel. Throughout his ordeal, he held on to the colors.

Cheers greeted him when Carney finally staggered into the ranks of the 54th. Before collapsing, he said, “Boys, the old flag never touched the ground!”

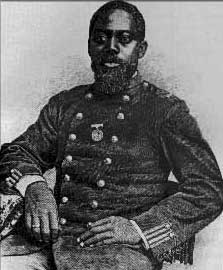

Several months later Sergeant William Carney, propped up on a cane from the injuries to his right leg, posed for a picture holding the flag he had risked so much for that day at Fort Wagner. The following year he was discharged from the army for the disabilities of his wounds. William Carney never realized his dream of becoming a minister. Moving back to New Bedford he worked for several years as a mail carrier. After that he worked as a messenger in the Massachusetts State House.

It was not unusual for acts of valor accomplished during the Civil War to go unrecognized for many years. More than half of the 1520 Medals of Honor awarded for heroism during that period were not awarded until 20 or more years after the war. On May 23, 1900 Sergeant William Harvey Carney was awarded his Nation’s highest award, the Medal of Honor. Though by that time several other black Americans had already received the award for heroism during the Civil War and the Indian Campaigns, Sergeant Carney’s action at Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863 was the first to merit the award.

William Harvey Carney died at his home in New Bedford on December 9, 1908, and is buried in the Oak Grove Cemetery there. His final resting place bears a distinctive stone, one claimed by less than 3500 Americans. Engraved on the white marble is a gold image of the Medal of Honor, a tribute to a courageous soldier and the flag he loved so dearly.

Sources:

https://www.historynet.com/william-h-carney-54th-massachusetts-soldier-and-first-black-us-medal-of-honor-recipient/

https://www.homeofheroes.com/hallofheroes/1st_floor/flag/1bfa_hist5carney.html

https://www.geni.com/people/William-H-Carney-Medal-of-Honor/6000000012677129291