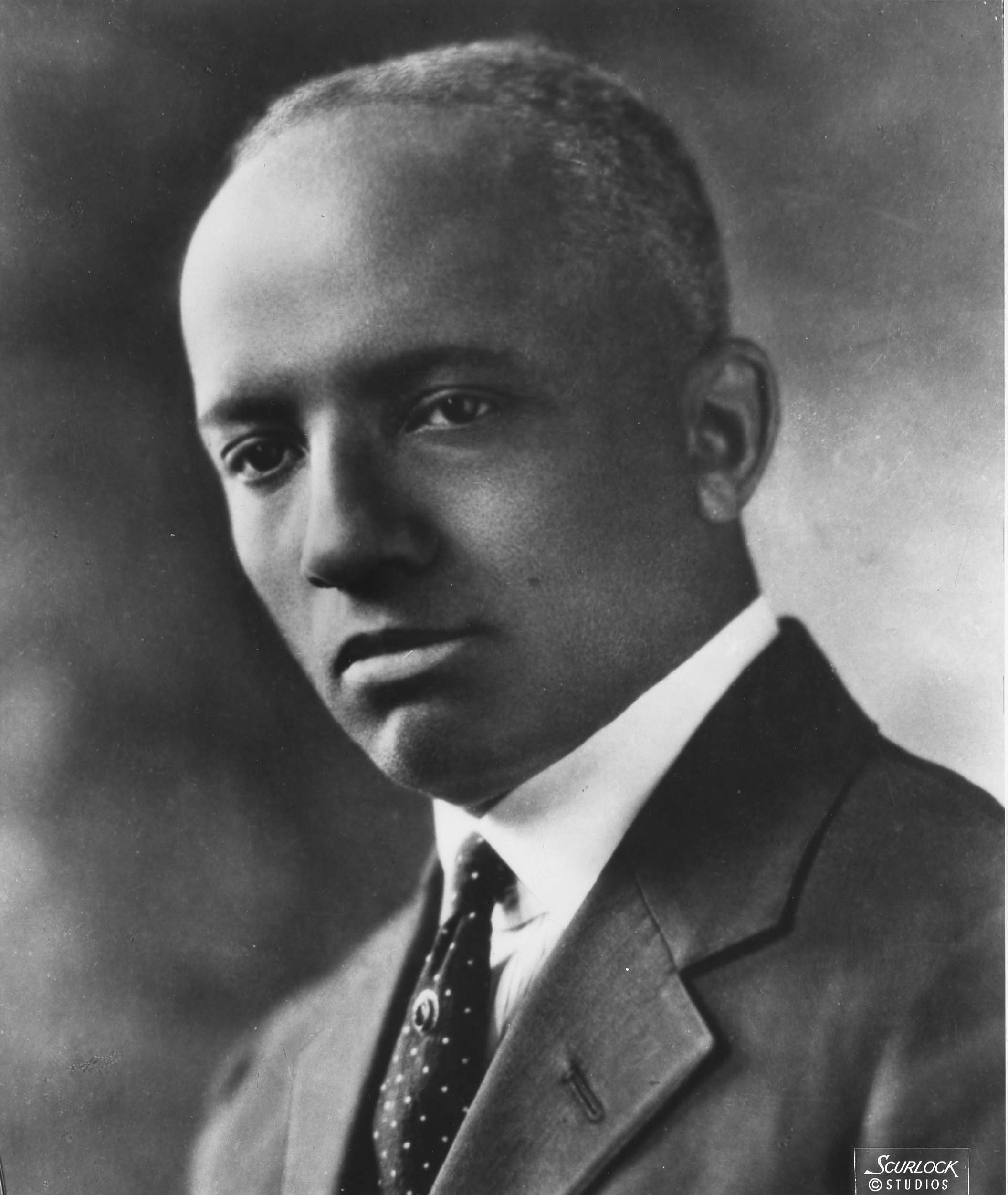

Carter G. Woodson, known as The Father of Black History, was the African American historian who first opened the long-neglected field of Black studies to scholars and also popularized the field in the schools and colleges of Black people. Woodson created Negro History Week (which later turned into Black History Month) in 1926 to focus attention on Black contributions to civilization.

Woodson was born on December 19, 1875 in New Canton, Virginia, the son of James Henry Woodson, a sharecropper, and Anne Eliza Riddle. His grandfather and father, who were skilled carpenters, were forced into sharecropping after the Civil War. The family eventually purchased land and eked out a meager living in the late 1870s and 1880s.

Woodson’s parents instilled in him high morality and strong character through religious teachings and a thirst for education. One of nine children, Woodson purportedly was his mother’s favorite, and was sheltered. As a small child he worked on the family farm, and as a teenager he worked as an agricultural day laborer. In the late 1880s the Woodsons moved to Fayette County, West Virginia, where his father worked in railroad construction, and where he himself found work as a coal miner. In 1895, at the age of twenty, he enrolled in Frederick Douglass High School where, possibly because he was an older student and felt the need to catch up, Woodson completed four years of course work in two years and graduated in 1897. Desiring additional education, Woodson enrolled in Berea College in Kentucky, which had been founded by abolitionists in the 1850s for the education of ex-enslaved persons. Although he briefly attended Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, Woodson graduated from Berea in 1903, just a year before Kentucky passed the “Day Law,” prohibiting interracial education. After college, Woodson taught at Frederick Douglass High School in West Virginia. Believing in the uplifting power of education, and desiring the opportunity to travel to another country to observe and experience the culture firsthand, he decided to accept a teaching post in the Philippines, teaching at all grade levels, and remained there from 1903 to 1907.

Woodson’s world view and ideas about how education could transform society, improve race relations, and benefit the lower classes, were shaped by his experiences as a college student and as a teacher. Woodson took correspondence courses through the University of Chicago because he was determined to obtain additional education. He was enrolled at the University of Chicago in 1907 as a full-time student and earned a bachelor’s degree, and a master’s degree in European history, submitting a thesis on French diplomatic policy toward Germany in the eighteenth century. Woodson then attended Harvard University on scholarships, matriculating in 1909 and studying with Edward Channing, Albert Bushnell Hart, and Frederick Jackson Turner. In 1912 Woodson earned his Ph.D. in history, completing a dissertation on the events leading to the creation of the state of West Virginia after the Civil War broke out. Unfortunately, he never published the dissertation. He taught at the Armstrong and Dunbar/M Street high schools in Washington from 1909 to 1919, and then moved on to Howard University, where he served as dean of arts and sciences, professor of history, and head of the graduate program in history in 1919-1920.

The Journal of Negro History, which Woodson edited until his death, served as the centerpiece of his research program, not only providing black scholars with a medium in which to publish their research but also serving as an outlet for the publication of articles written by white scholars, when their interpretations of such subjects as the Maafa (slavery) and black culture differed from mainstream historians. Woodson formulated an editorial policy that was inclusive. Topically, the Journal provided coverage in various aspects of the black experience: The Maafa (slavery, the slave trade), black culture, the family, religion, and antislavery and abolitionism, and included biographical articles on prominent African Americans. Chronologically, articles covered the sixteenth through the twentieth centuries. Scholars, as well as interested amateurs, published important historical articles in the Journal, and Woodson kept a balance between professional and nonspecialist contributors.

Woodson began celebration of Negro History Week to increase awareness of and interest in black history among both blacks and whites. He chose the second week of February to commemorate the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. Each year he sent promotional brochures and pamphlets to state boards of education, elementary and secondary schools, colleges, women’s clubs, black newspapers and periodicals, and white scholarly journals suggesting ways to celebrate. The association also produced bibliographies, photographs, books, pamphlets, and other promotional literature to assist the black community in the commemoration. Negro History Week celebrations often included parades of costumed characters depicting the lives of famous blacks, breakfasts, banquets, lectures, poetry readings, speeches, exhibits, and other special presentations. During Woodson’s lifetime, the celebration reached every state and several foreign countries.

Among the major objectives of Woodson’s research and the programs he sponsored through the Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History (the name was changed in the 1970s to reflect the changing times) was to counteract the racism promoted in works published by white scholars. With several young black assistants–Rayford W. Logan, Charles H. Wesley, Lorenzo J. Greene, and A. A. Taylor–Woodson pioneered in writing the social history of black Americans, using new sources and methods, such as census data, enslaved persons testimony, and oral history. These scholars moved away from interpreting blacks solely as victims of white oppression and racism toward a view of them as major actors in American history. Recognizing Woodson’s major achievements, the NAACP presented him its highest honor, the Spingarn Medal, in June 1926. At the award ceremony, John Haynes Holmes, the minister and interracial activist, cited Woodson’s tireless labors to promote the truth about Negro history.

During the 1920s Woodson funded the research and outreach programs of the association with substantial grants from white foundations such as the Carnegie Foundation, the General Education Board, and the Laura Spellman Rockefeller Foundation. Wealthy whites, such as Julius Rosenwald, also made contributions. White philanthropists cut Woodson’s funding in the early 1930s, however, after he refused to affiliate the association with a black college. During and after the depression, Woodson depended on the black community for his sole source of support.

In 1915, Woodson published his first book, The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861 and co-founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH). In 1916, he singlehandedly launched The Journal of Negro History, now The Journal of African American History. In 1918, Woodson published A Century of Negro Migration and became the principal of Armstrong Manual Training School, Washington, D.C. From 1919 until 1920, he was the Dean of Howard University’s School of Liberal Arts and from 1920 until 1922 he served as a dean at West Virginia Collegiate Institute. In 1921, he published The History of the Negro Church and founded the Associated Publishers, Inc. After founding the ASNLH, he also became active in black organizations like the NAACP, the National Urban League, the Friends of Negro Freedom, and the Committee of 200.

Woodson also formed the African-American-owned Associated Publishers Press in 1921 and would go on to write more than a dozen books over the years, including A Century of Negro Migration (1918), The History of the Negro Church (1921), The Negro in Our History (1922) and Mis-Education of the Negro (1933). Mis-Education—with its focus on the Western indoctrination system and African-American self-empowerment—is a particularly noted work and has become regularly course adopted by college institutions.

Among the first scholars to investigate the Maafa from the enslaved person’s point of view, Woodson studied it comparatively as institutions in the United States and Latin America. His work prefigured the concerns of later scholars of the Maafa by several decades, as he examined enslaved persons resistance to bondage, the internal slave trade and the breakup of slave families, miscegenation, and blacks’ achievements despite the adversity of the Maafa.

Woodson focused mainly on the Maafa in the antebellum period, examining the relationships between owners and enslaved and the impact of the Maafa upon the organization of land, labor, agriculture, industry, education, religion, politics, and culture. Woodson also noted the African cultural influences on African-American culture. In The Negro Wage Earner (1930) and The Negro Professional Man and the Community (1934) Woodson described class and occupational stratification within the black community. Using a sample of 25,000 doctors, dentists, nurses, lawyers, writers, and journalists, he examined income, education, family background, marital status, religious affiliation, club and professional memberships, and the literary tastes of black professionals. He hoped that his work on Africa would “invite attention to the vastness of Africa and the complex problems of conflicting cultures.”

Woodson also pioneered in the study of black religious history. A Baptist who attended church regularly; he was drawn to an examination of black religion because the church functioned as an educational, political, and social institution in the black community and served as the foundation for the rise of an independent black culture. Black churches, he noted, established kindergartens, women’s clubs, training schools, and burial and fraternal societies, from which independent black businesses developed. As meeting places for kin and neighbors, black churches strengthened the political and economic base of the black community and promoted racial solidarity. Woodson believed that the “impetus for the uplift of the race must come from its ministry,” and he predicted that black ministers would have a central role in the modern civil rights movement.

Woodson never married or had children, and he died at his Washington home on April 3rd, 1950; he had directed the association until his death. For thirty-five years he had dedicated his life to the exploration and study of the African-American past. Woodson made an immeasurable and enduring contribution to the advancement of black history through his own scholarship and the programs he launched through the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History.

Sources:

http://www.anb.org/articles/14/14-00718.html

http://www.britannica.com/biography/Carter-G-Woodson

http://www.blackpast.org/aah/woodson-carter-g-1875-1950#sthash.x3g48tF6.dpuf

http://www.biography.com/people/carter-g-woodson-9536515#writing-mis-education-of-the-negro