In 1441, Antam Goncalvez, a Portuguese sailor, seized ten Africans near Cape Bojador. According to Azurara, the Portuguese chronicler, Goncalvez was to sail along the western shore of Africa, not to try for new discoveries but to prove his worth by shipping a cargo of skins and the oil of ‘sea wolves’ (sea lions). Goncalvez and his crew travelled as far as the southern seaboard of what became Morocco. Once judging that he had traveled far enough to win a reputation, Goncalvez conceived the idea that he could please his royal master, Prince Henry of Portugal, by capturing some of the inhabitants of this unknown southern land. Goncalvez went ashore with nine of his crew. When they were around three league distant from the sea, they found the footmarks of men and youths, the number of whom, according to their estimate, would be from forty to fifty.’ However, the footprints were going in a opposite direction from where our men were going. Goncalvez and his men decided to turn back, but while returning over the sand-warm dunes to the sea, they saw a Moor following a camel, with two assegais in his hand, and pursued him. Though he was only one, he defended himself as best as he could, showing great courage. ‘But Affonso Goterres wounded him with a javelin…’ The Portuguese took him prisoner and then as they were going on their way, they saw a Black Mooress come along, and so they seized her too.

This initial piratical act of violence would eventually spiral into more terrifying forms – warfare and raids- for the enslavement of African people.

For over 400 years, African people were exploited by Europeans for the creation and development of a number of their invaded territories across the Americas. Over the long history of the Atlantic slave system, Africans in their millions were removed from their varied homelands and loaded onto slave ships. There were two distinct stages on the journey from Africa to the Americas: Capture in Africa; and the Atlantic crossing, which Europeans call the Middle Passage. At both stages, the captive people suffered unimaginable cruelties, as the Atlantic slave system was initiated and perpetuated in conditions of extreme violence. Nothing in their life experiences could have prepared African people for the psychological trauma, dehumanization, and degradation, they would experience. An estimated 40 percent of the captives died before leaving Africa. During the so-called ‘Middle Passage’ between 10 and 20 percent of over 15 million who departed Africa died from punishments, hunger, disease, and trauma; large numbers were also thrown overboard when slavers considered them sick.

One of the most horrific books, I have ever read on the Maafa (slavery) is If We Must Die by Eric Robert Taylor. Although Taylor’s book, was on shipboard insurrections (he found 493 cases), he began his book with a comprehensive introduction of the Maafa (Atlantic slavery) to really convey the brilliance of African resistance in the face of overwhelming odds. However, time and time again, during the reading of this book, I had to put it away. It was just too painful! It was the first book, I had to stop reading for weeks before I could go back to it. If We Must Die, offers a vivid account of the horror of the Maafa. Most of the traumatic experiences of our ancestors detailed below are taken from Taylor’s book.

Knowing the soul wounding, which could result from reading the brutal savagery our ancestors experienced, I have included three videos. The first video, “There is no movement without rhythm” will connect you to sounds and spirit of our ancestors. Please play this video and allow the music to accompany you as you read. The second video is on Water Drumming, as the sound of water is very healing for the soul. The third video, by Sobonfu Some is on “Crying: The Ritual of Healing.”

And remember the words of Maya Angelou, “It takes more than a horrifying transatlantic voyage chained in the filthy hold of a slave ship to erase someone’s culture.”

1

Whatever the method of capture, Africans usually made the journey to the coast on foot. They often endured a long trek fastened one to the other, loaded with heavy stones of 40 or 50 pounds in weight to prevent attempts at escape. A European who accompanied one such trafficking reported in 1799 that a typical coffle in the Senegal River area would march some twenty miles in seven or eight hours each day. To control the captives and discourage resistance on these long journeys, not only were they manacled, they were also whipped and deprived of sleep. Guards would sometimes even keep the entire group awake for days on end, “seating them each night around a large fire, and kicking any who managed to dozed off back to wakefulness.” Poor supply of food and water meant that the captives often suffered from severe malnutrition and dehydration. On the long journey to the coast, sometimes hundreds of miles, nearly half of the newly captured Africans died on the way. The trails to the coast were littered with skeletons. As one slave-merchant noted, slavers in the latter half of the eighteenth century expected to lose approximately 40 percent of their captives to either flight or death before reaching the slave ships.

Some captives were brought to the coast by canoe forced to lie in the the bottom of boats for days on end, with their hands bound, their faces exposed to the tropical sun and the tropical rain, their backs in the water which was never bailed out. The strongest Africans would be additionally tied at the knees. As Alexander Falconbridge (a British surgeon who took part in four voyages in slave ships between 1780 and 1787) noted in 1788, “[The Africans’] allowance of food is scanty, that it is barely sufficient to support nature. They are, besides, much exposed to the violent rains which frequently fall here, being covered only with mats that afford but a slight defence; and as there is usually water at the bottom of the canoes, from their leaking, they are scarcely ever dry.”

2.

At the coast, the captives were force to undergo a humiliating physical inspection. They were carefully examined from head to toe, without regard to sex, to see that they did not have any blemishes or defects. They were poked and prodded, had their limbs and teeth checked, and were inspected for any signs of disease. Some were rejected if defects were identified, as Invalides. An eighteenth-century Dutch slaving handbook recommended that traders check the hearing and speaking ability of captives by making them scream. Among the slavers was a clear preference for fifteen to twenty-five-year-old males, who represented about two thirds of the captives. Therefore in order to avoid purchasing older Africans, slavers were advised to check the captives’ teeth, examine their hair, and test the firmness of women’s breasts. The captives could endure as much as four hours of inspection. Armed guards were usually in attendance at these inspections and the captives had no choice but to endure the humiliation.

Once deemed acceptable, many then had to endure the further indignity of being branded. Some were branded multiple times before leaving Africa and often yet again upon arrival in the Americas. The branding process was especially painful. After the irons were heated red hot on a bed of burning charcoal, several traffickers would hold the captive in place while another would rub the spot intended for branding with tallow and then place a piece of greased or oiled paper over it. The branding iron would then be pressed into the piece of paper. These marks were variously made on the shoulder, breast, thigh, stomach, or even on the buttocks in the case of small children, and took four to five days to heal.

Once purchased some were sold in small numbers to ships along the coastline and other were usually imprisoned at forts and factories staffed by Europeans, until the arrival of ships that would take them to the Americas.

3.

Those imprisoned, were put in the dark pen of a fort or a makeshift pen constructed on the beach waiting to be sold. The fort at Cape Coast was “cut out of the rocky ground, arched and divided into several rooms underground in such a way that it easily imprisoned a thousand Africans.” Describing the barracoons, Joseph Miller writes, “Large numbers of [captives] accumulated within these pens, living for days and weeks surrounded by walls too high for a person to scale, squatting helplessly, naked, on the dirt and entirely exposed to the skies except for a few adjoining cells where they could be locked at night. They lived in a ‘wormy morass’…and slept in their own excrement, without even a bonfire for warmth.”

Some pens sometimes held 150 to 200 captives, along with pigs and goats, leaving only about two square meters for each captive. Africans were sometimes forced to suffer these conditions for months on end.

Another observer noted, “[The captives] were confined in prisons or dungeons, resembling dens, where they lie naked on the sand, crowded together and loaded with irons. In consequence of this cruel mode of confinement, they are frequently covered with cutaneous eruptions. Ten or twelve of them feed together out of a trough, precisely like so many hogs.”

To make matters worse, diseases periodically ravaged the dirty and crowded pens, and the captives became progressively weakened by their extended confinement. Death rate were extremely high. When they died, their bodies would be thrown onto the beach to rot to be picked over by wild animals.

In the Dutch fort, some captives were put to work during their detention.

In addition, at these fortresses, women were subjected to the sexual violence of European men stationed there to oversee the gruesome business of enslavement. Imprisoned women were also required to clean and cook for them.

4.

When slave ships anchored off shore, imprisoned men, women and children on shore would be stripped naked and ferried in small groups to the floating hell. The condition on slave ships were foul. Ottabah Cugoano described the arrival of a slave ship as the “most horrible scene; there was nothing to be heard but the rattling of chains, smacking of whips, and the groans and cries of our fellow men.” Many refused to get in the boats and flung themselves on the sand in an effort to stay on land. Special appointed “captains of the sand” would beat, dragged and/or otherwise forced them into the canoes.

Finally onboard, the men, who were perceived to be more of a threat than the women, were chained right leg to left leg and sometimes by the hands and even the neck as well, and all were loaded securely below.

In addition to the slave holds, some slavers built half-decks along the sides of the ships, extending no farther than the sides of the scuttles, where captives, lying in two rows, one above the other, were crowded together and were fastened by leg irons. Captives were brought upon deck at mid-morning and those who had died during the night were thrown into the ocean.

Once a loaded slave ship left the African coast the terrifying seven-to-eight-week journey to the Americas began.

5.

Contributing to the situation was the fear that they were being captured to be eaten. This fear was not unfounded.

“Fear of Africans bred a savage cruelty in the slaver. One slaver, to strike terror in the captives, killed a captive and divided the heart, liver and entrails into 300 pieces and made each captive eat one; threatening those who refused with the same torture. Such incidents were not rare.”

Therefore, Africans often believed that they were being carried away to be offered as human sacrifices to gods of the European man’s religion or to be murdered to provide blood to dye cloth red. Others were convinced that their body fat would be processed into products such as oil, or lard or that their brains were to be made into cheese. The black shoe leather of the Europeans was sometimes mistaken for African skin, while gunpowder was similarly considered by some to be the burnt and ground bones of previous captives.

On the Prince of Orange in 1737, one hundred captives decided to jump overboard in an apparent mass suicide attempt, believing that the Europeans were planning to pluck out their eyes and then make a meal of them. Thirty three of the men refused to be saved and “sunk directly down.”

6

To control the captives’ food consumption, the process of eating was sometimes directed by signals from a monitor, who indicated when the captives should dip their fingers or wooden spoons into the food and when they should swallow. It was the responsibility of the monitor to report those who refused to eat, and any captive found to be attempting to starve themselves were severely whipped. According to a ship’s surgeon, “Upon the [African] refusing to take sustenance I have seen coals of fire, glowing hot, put on a shovel, and placed so near their lops as to scorch and burn them. And this has been accompanied with threats of forcing them to swallow the coals, if they any longer persisted in refusing to eat.” At other times, the speculum orum, a mouth opener was used to force-feed the captives.

7.

“The loathsomeness and filth of that horrible place will never be effaced from my memory; nay, as long as memory hold her seat in this distracted brain, will I remember that. My heart even at this day, sickens at the thought of it.” As one survivor remembered.

The suffocating condition on slave ships meant that captives as well as traffickers were afflicted by fevers, dysentery and smallpox. The biggest killer of all was dysentery or the notorious “bloody flux,” which may have accounted for a third of all deaths. This disease was an infection of the intestines resulting in frequent bowel moments, vomiting, severe abdominal pain, headaches and high fevers. The disease got its name from the fact that those who suffered from it would often lose blood as a result of ulcerated intestines.

8

Fights among Africans in the ship holds also took place, as strangers who now found themselves chained to one another struggled for personal space. One entry in the log of the slave ship Sandown reveals that the ship’s doctor had to amputate the infected finger of an African bitten by another captive. Similarly the log of the Danish ship Fredensborg noted that two captives were whipped for fighting. On the Lady Mary, fights among the captives were responsible for several deaths.

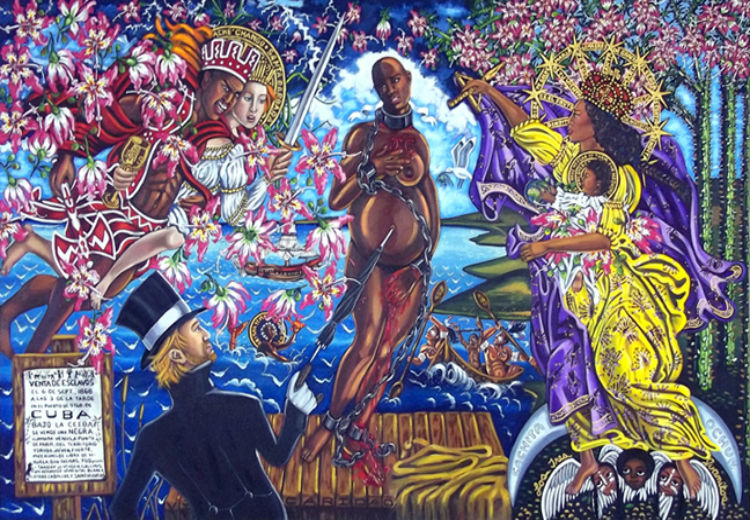

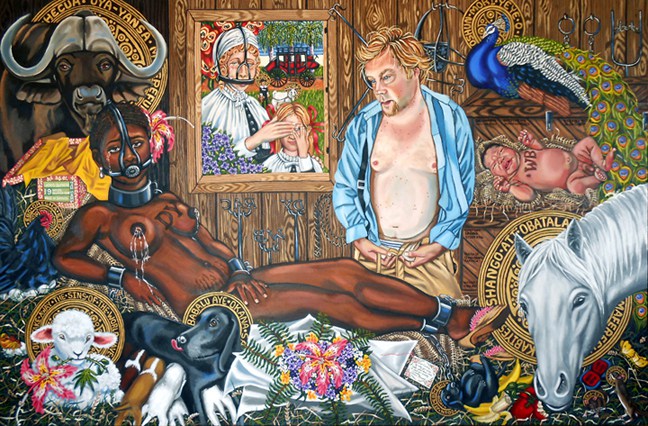

*Artwork: Caroline (after Édouard Manet’s Olympia, 1863), by Lili Bernard. Oil on Canvas, 63”x96”, 96”x63” © 2012.

Lili Bernard stated that the painting “is a memoriam to my great-grandmother Caroline who was a very poor dark-skinned Black maidservant for my great-grandfather William Bernard. William was a rich [Whyte] stage coach designer in Kingston, Jamaica, and was married with children. Caroline bore three babies from William: my grandmother Harriet and her brothers William and Nathan Bernard. We assume they were born out of rape. Visit her website.

9.

The true horrors of the Middle Passage would be incomplete without acknowledging the abuse of the female captives by slavers and traffickers. It is possible that a major reason the men’s and women’s quarter were separate on slave ships was so that the traffickers could have easier access to the women without dealing with angry African men. The slaver, John Newton, who composed Amazing Grace, wrote: “When the women and girls are taken on board a ship, naked, trembling, terrified, perhaps almost exhausted with cold, fatigue and hunger, they are often exposed to the wanton rudeness of [whyte] savages.”

It is possible that the rape of African women and girls occurred on just about every slave ship that crossed the Atlantic with African women. The comments of a French slaver anchored at Whydah in 1792 are telling. Fearing rebellion on board after witnessing revolt nearby, the slaver lamented: “To avoid a similar incident, we put the largest part of our [Africans] in irons, and even among the [women] those who appeared to us the most resolute and the most dangerous…although because of their beauty they were very dear to the chief [slavers] and [traffickers] who had each given their names to chosen ones, there was nothing left to do but put them in chains.”

Another French slaver wrote in his memoirs that each officer of his ship selected an African woman to serve him “at the table and in his bed.” Ottobah Cugoano acknowledged the prevalence of sexual abuse in a much different tone, angrily recalling that “it was common for the dirty filthy [traffickers] to take the African women and lie upon their bodies.”

As one historian writes: “For the attractive woman there was the added ignominy of being fought over by lustful [whyte] men. Quarrels erupted, insults and blows were exchanged to win the right to be the first to rape a good-looking Black woman, or the right to make her one’s exclusive sexual possession for the duration of the voyage.”

A certain Slaver Liot “mistreated a pretty [Black woman], broke two of her teeth and put her in such a state of languish that she could only be sold for a very low price at Saint Domigue where she died two weeks later. Not content the said Philippe Liot pushed his brutality to the point of violating a little girl of eight to ten years, whose mouth he closed to prevent her from screaming. This he did on three nights and put her in a deathly state.” On Dutch ship although sexual contact with African women was forbidden, the female quarters were often referred to as the hoeregat, or “whore hole,” clearly referring to the sexual exploitation that obviously occurred there.

10.

Africans captives and traffickers alike were killed by catastrophic accidents. The wooden ships would frequently be struck by lightning and burn, get blown off course for months, run aground on shallow coastal rocks, or encounter hurricanes in the mid-Atlantic and sink. The Danish Cron-Prindzen was lost in a storm in 1705, for example, causing the deaths of some 820 captives. In January 1738, the Dutch Leusden was similarly caught in a storm off the Suriname coast and got caught on the rocks. While the traffickers and a few of the captives escaped 700 Africans below deck drowned. In 1737, some 200-300 Africans drowned when the ship Mary sprang a leak. The Liverpool vessel Pallas was slaving on the African coast in 1761, when she mysteriously blew up, taking some 600 captives with her. 380 captives were reported killed when the London ship Den Keyser blew up on the African coast in 1783. On its ways to Havana in 1787, the Sisters capsized in the West Indies, drowning nearly 500 captives. Furthermore, slavers often faced the threat of attack by interlopers, privateers, or pirates, and warships were always a problem as European nations waged seemingly endless wars. When the French Hercule found itself in combat with a Dutch warship in 1701 during the War of Spanish succession, the captives on board paid a high price. Outfought, the French ship exploded and burned, killing thirty-eight Africans.

“May those who died rest in peace. May those who return find their roots. May humanity never again perpetrate such injustice against humanity. We the living vow to uphold this.” ~P.J. Patterson (2006)

Nb: In this article we use the word Slaver for Captain and Traffickers for sailors/crew.

For more of the Lili Bernard’s artwork visit http://lilibernard.com/site/artwork/

Source:

If We Must Die by Eric Robert Taylor

Trans Atlantic Slavery: Against Human Dignity edited by Anthony Tibbles

The Black Jacobins by C.L.R. James

Britain’s Slave Empire by James Walvin