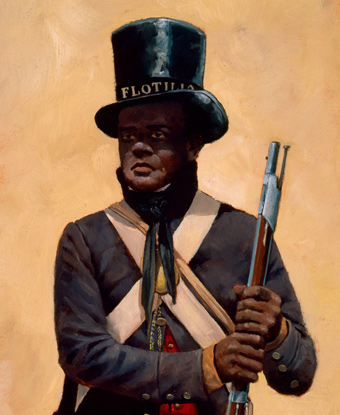

Charles Ball was an enslaved African-American from Maryland, best known for his account as a fugitive, The Life and Adventures of Charles Ball (1837). Ball also served the United States in the War of 1812 and fought at the Battle of Bladensburg on August 24, 1814.

Charles Ball was an enslaved African-American from Maryland, best known for his account as a fugitive, The Life and Adventures of Charles Ball (1837). Ball also served the United States in the War of 1812 and fought at the Battle of Bladensburg on August 24, 1814.

Charles Ball was born in about 1780. His grandfather was brought from Africa and his mother was enslaved on a tobacco planter. When the enslaver died when Ball was four years old, his family were sold separately, with his mother going to Georgia: “My mother had several children, and they were sold upon [enslaver’s] death to separate purchasers. She was sold, my father told me, to a Georgia trader. I, of all her children, was the only one left in Maryland. When sold I was naked, never having had on clothes in my life, but my new [enslaver] gave me a child’s frock, belonging to one of his own children. After he had purchased me, he dressed me in this garment, took me before him on his horse, and started home; but my poor mother, when she saw me leaving her for the last time, ran after me, took me down from the horse, clasped me in her arms, and wept loudly and bitterly over me.”

Ball stayed with his father until he was about 12 years old, when his enslaver, Jack Cox, died. Ball later recalled in his autobiography, “I was sorry for the death of my enslaver, who had always been kind to me; and I soon discovered that I had good cause to regret his departure from this world. He had several children at the time of his death, who were all young; the oldest being about my own age. The father of my late enslaver, who was still living, became administrator of his estate and took possession of his property, and amongst the rest, of myself. This old gentleman treated me with the greatest severity, and compelled me to work very hard on his plantation for several years.”

When he was approximately 20 years old, around 1800, Ball’s enslaver hired him out to the Navy. When Ball arrived at the Washington Navy Yard, he was stationed as a cook aboard the USS Congress. After nearly two years in the service of the Navy, Ball encountered a free Black sailor from Philadelphia. Together, they devised a scheme to smuggle Ball to freedom in the North, but no sooner did they complete their plan than Ball’s former enslaver returned to reclaim him and sell him again, eventually away from his family to a cotton plantation owner in South Carolina.

“I had at times serious thoughts of suicide so great was my anguish. If I could have got a rope I should have hanged myself at Lancaster. The thought of my wife and children I had been torn from in Maryland, and the dreadful undefined future which was before me, came near driving me mad.” Ball made several attempts to escape but was captured and became enslaved by another man in Georgia.

After seven years in South Carolina, Ball escaped back up to Maryland to be closer to his family. “It was now clear that some slave-dealer had come in my absence and seized my wife and children, and sold them to such men as I had served in the South. They had now passed into hopeless bondage and were gone forever beyond my reach. I myself was advertised as a fugitive, and was liable to be arrested at each moment, and dragged back to Georgia. I rushed out of my own house in despair and returned to Pennsylvania with a broken heart.”

Declaring himself a free man, Ball worked at small farms until war broke out in the Chesapeake. Although Ball could have secured his freedom by joining with the British and being evacuated from the United States, instead he chose to stay and enlist under Commodore Joshua Barney as a free man, attempting to convince other fugitives to stay in the United States and fight rather than defect to the British. Ball served as a seaman and a cook in the Chesapeake flotilla, serving at the Battle of Bladensburg and later he helped man the defenses at Baltimore. In his memoir, Ball reflected on the Battle of Bladensburg: “I stood at my gun until the Commodore was shot down… if the militia regiments, that lay upon our right and left, could have been brought to charge the British, in close fight, as they crossed the bridge, we should have killed or taken the whole of them in a short time; but the militia ran like sheep chased by dogs.”

After the war, Ball remained in Baltimore, living as a free man and eventually purchasing land for a home. This peace would be short, however: in 1830, he was seized as a fugitive and sold to a plantation in Georgia. Although he eventually escaped and returned to the north, living outside Philadelphia, he never was able to reunite with his family.

With the help of Isaac Fisher, a whyte lawyer, Ball wrote his autobiography. It included the following passage: “For the last few years, I have resided about fifty miles from Philadelphia, where I expect to pass the evening of my life, in working hard for my subsistence, without the least hope of ever again seeing, my wife and children: – fearful, at this day, to let my place of residence be known, lest even yet it may be supposed, that as an article of property, I am of sufficient value to be worth pursuing in my old age.” Afraid of being recaptured, Ball moved again and its is not known when and where he died.

Source:

http://spartacus-educational.com/USASball.htm

http://www.nps.gov/people/charles-ball.htm