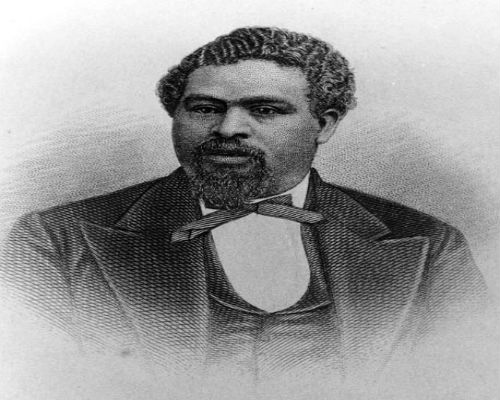

Robert Smalls was an enslaved African American who distinguished himself as a national war hero, statesman and civil-rights leader in the Reconstruction South, serving five terms in the United States House of Representatives. Smalls is perhaps best known for his role in turning over the CSS Planter, an armed Confederate military transport, to the Union Navy. Smalls took eight men, five women and three children, all enslaved with him. As a result, he had a meeting with President Lincoln convincing him of the importance of allowing African Americans to serve in the U.S. Army.

Robert Smalls was born in Beaufort, South Carolina, on April 5th, 1839, in a slave cabin behind his mother’s enslaver’s house on 511 Prince Street. It’s widely believed that Henry McKee, the enslaver, was Smalls’s father. When he was 12, McKee sent Smalls to work in Charleston, where Smalls working at a variety of jobs aboard boats, eventually trained to be a river pilot and learned to navigate the tricky waterways of Charleston harbor. Most of his wages went back to McKee. At the beginning of the Civil War, Smalls worked onboard the Planter, a civilian boat contracted by the Confederate navy as a transport. In 1862 he escaped from Charleston harbor aboard the Planter with his family and several friends too. The boat had to pass by five Confederate check-points and then surrender its contents to the northern Naval fleet out in the harbor where it was blockading the important southern port.

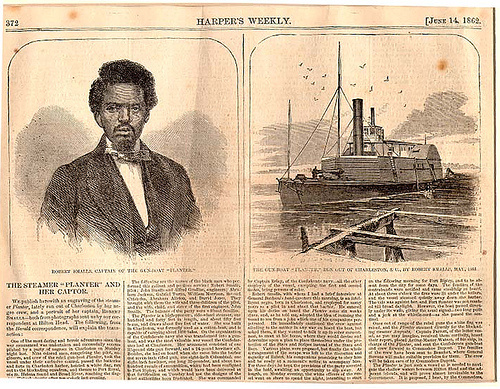

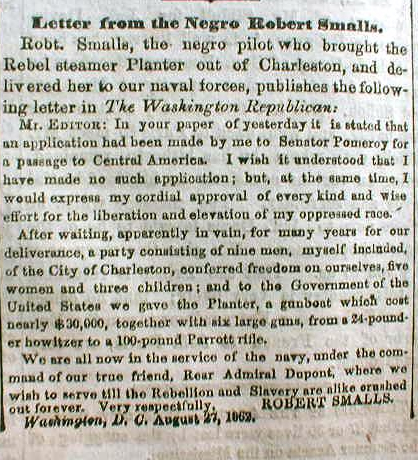

Harper’s Weekly published a prominent article entitled “The Steamer Planter and Her Captor,” June 14, 1862: pp 372-373.

“One of the most daring and heroic adventures since the war commenced was undertaken and successfully accomplished by a party of [Blacks] in Charleston on Monday night last. Nine [Black] men, comprising the pilot, engineers, and crew of the rebel gun-boat Planter, took the vessel under their exclusive control, passed the batteries and forts in Charleston harbor, hoisted a white flag, ran out to the blockading squadron, and thence to Port Royal, via St. Helena Sound and Broad River, reaching the flag-ship Wabash shortly after ten o’clock last evening.

The following are the names of the Black men who performed this gallant and perilous service: Robert Smalls, pilot; John Smalls and Alfred Gradine, engineers; Abraham Jackson, Gabriel Turno, William Morrison, Samuel Chisholm, Abraham Allston, and David Jones. They brought with them the wife and three children of the pilot, and the wife, child, and sister of the first engineer, John Smalls. The balance of the party were without families.

The Planter is a high-pressure, side-wheel steamer, one hundred and forty feet in length, and about fifty feet beam, and draws about five feet of water. She was built in Charleston, was formerly used as a cotton-boat, and is capable of carrying about 1400 bales. On the organization of the Confederate navy she was transformed into a gun-boat, and was the most valuable war vessel the Confederates had at Charleston. Her armament consisted of one 32-pound rifle gun forward, and a 24-pound howitzer aft. Besides, she had on board when she came into the harbor one seven-inch rifled gun, one eight-inch Columbiad, one eight-inch howitzer, one long 32-pounder, and about two hundred rounds of ammunition, which had been consigned to Fort Ripley, and which would have been delivered at that fortification on Tuesday had not the designs of the rebel authorities been frustrated. She was commanded by Captain Relyea, of the Confederate navy—all the other employes of the vessel, excepting the first and second mates, being persons of color.

Robert Smalls, with whom I had a brief interview at General Benham’s head-quarters this morning, is an intelligent [Black man], born in Charleston, and employed for many years as a pilot in and about that harbor. He entered upon his duties on board the Planter some six weeks since, and, as he told me, adopted the idea of running the vessel to sea from a joke which one of his companions perpetrated. He immediately cautioned the crew against alluding to the matter in any way on board the boat, but asked them, if they wanted to talk it up in sober earnestness, to meet at his house, where they would devise and determine upon a plan to place themselves under the protection of the Stars and Stripes instead of the Stars and Bars. Various plans were proposed, but finally the whole arrangement of the escape was left to the discretion and sagacity of Robert, his companions promising to obey him and be ready at a moment’s notice to accompany him. For three days he kept the provisions of the party secreted in the hold, awaiting an opportunity to slip away. At length, on Monday evening, the white officers of the vessel went on shore to spend the night, intending to start on the following morning for Fort Ripley, and to be absent from the city for some days. The families of the contrabands were notified and came stealthily on board. At about three o’clock the fires were lit under the boilers, and the vessel steamed quietly away down the harbor. The tide was against her, and Fort Sumter was not reached till broad daylight. However, the boat passed directly under its walls, giving the usual signal—two long pulls and a jerk at the whistle-cord—as she passed the sentinel.

Once out of range of the rebel guns the white flag was raised, and the Planter steamed directly for the blockading steamer Augusta. Captain Parrott, of the latter vessel, as you may imagine, received them cordially, heard their report, placed Acting-Master Watson, of his ship, in charge of the Planter, and sent the Confederate gun-boat and crew forward to Commodore Dupont. The families of the crew have been sent to Beaufort, where General Stevens will make suitable provision for them. The crew will be taken care of by Commodore Dupont.

The Planter is just such a vessel is needed to navigate the shallow waters between Hilton Head and the adjacent islands, and will prove almost invaluable to the Government. It is proposed, I hear, by the Commodore, to recommend an appropriation of $20,000 as a reward to the plucky Africans who have distinguished themselves by this gallant service—$5000 to be given to the pilot, and the remainder to be divided among his companions.”

Smalls met with Abraham Lincoln who was quite impressed with him and gave him a commission into the Union Navy as a captain of a vessel – the Planter! Smalls became one of the first African American pilots in the United States Navy. As captain, he led the Planter into 17 battles. In April 1863, he piloted the experimental ironclad USS Keokuk, which received so many direct hits from Confederate batteries that it sank in Charleston Harbor. He was also wounded on April 7, 1863. Smalls was also influential in Lincoln’s approval of the first Black troops; the 1st South Carolina Infantry of U.S. Colored Troops.

After the Civil War, Smalls founded the Beaufort County Republican Club and once famously said that it was “the party of Lincoln which unshackled the necks of four million human beings.” Smalls served in the South Carolina House and Senate from 1865 to 1874, was a delegate to the South Carolina Constitutional Convention in 1868, and served in Congress off and on from 1875 to 1887. Part of the gap in his congressional service was due to false accusations in 1877 that he took a $5,000 bribe. Smalls was framed by so-called Redeemers, Democrats who wanted to see the South go back to the days of slavery and the plantation. Smalls was convicted in November 1877 but pardoned in 1879.

Despite these smears, Smalls was a power broker in local and national politics for more than 40 years. Known as the “King of Beaufort County,” he secured the first funds for the purchase of what is today Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island, raised money for Beaufort’s first public school and was a booster of economic development in a brief period when the county was a center of industry rather than agriculture.

Smalls was also a property owner and businessman. One of his properties was the house of his enslavers, the McKee family in Beaufort, now the McKee-Smalls House, which is on the National Register of Historic Places. Smalls was sitting on the porch of that home , on Prince Street, on Feb. 23, 1915, when his extraordinary life came to an end at age 76. Today, there is a naval ship named for him, as well as a school and a highway in Beaufort.

Source:

From slavery to Congressman – Robert Smalls

http://www.robertsmalls.net/

http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702303772904577335760567074258

http://www.islandpacket.com/2015/02/21/3600424/robert-smalls-who-rose-from-slavery.html