[dropcap size=big]R[/dropcap]ichmond Barthé was an African-American sculptor associated with the Harlem Renaissance. Barthe was one of the first sculptors to focus on Black people as his main subjects, achieving critical acclaim, commerical success, and widespread popularity. “Aesthetically, he brought a new insight to the individuality and physical grace of all types of Black people,” Romare Bearden and Harry Henderson wrote in A History of African-American Artists.

Richmond Barthé was born on January 28, 1901, in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi. He was the first and only child of Richmond Barthé Sr. and Marie Clementine Robateau. Barthé’s father died at age 22, when he was only few months old, leaving his mother to raise him alone. She worked as a dressmaker and before Barthé began elementary school she remarried to William Franklin, with whom she eventually had five additional children.

Barthé showed a passion and skill for drawing from an early age. His mother said that “Jimmie,” as she called him, “could draw before he could walk.” Barthé once said: “When I was crawling on the floor, my mother gave me paper and pencil to play with. It kept me quiet while she did her errands. At six years old I started painting. A lady my mother sewed for gave me a set of watercolors. By that time, I could draw very well.”

When he was only twelve years old, Barthé exhibited his work at the Bay St. Louis Country Fair. However, he suffered an attack of typhoid fever at age fourteen, which meant he had to withdrew from school. Following this, he then held various jobs in a restaurant, an office, and helping his stepfather on the ice truck. However, one of his stepfather’s whyte customers, an artist herself, was concerned that carrying cold ice on his shoulder might give him rheumatism and prevent him from painting. She introduced him to a wealthy New Orleans family, the Ponds, who hired him as a household servant.

Barthe moved with the Ponds to New Orleans, where he lived for the next nine years. The Ponds held liberal views about race for their time, and treated Barthe more as a member of the family than as a servant. They included him in social events in their home, took him to the theater, and encouraged him in his art. During his years with the Ponds, Barthe learned to feel comfortable in a range of social situations—a skill that would help him later in his career, when he was often commissioned by wealthy people to sculpt their portraits. The Ponds also introduced him to Lyle Saxon, a local writer for the Times Picayune. Saxon, who was fighting against the racist system of school segregation, tried unsuccessfully to get Barthé registered in an art school in New Orleans.

In 1924 Barthé donated his first oil painting to a local Catholic church to be auctioned at a church fundraiser. Impressed by his talent, Reverend Harry F. Kane raised money for Barthé to undertake studies in fine art. At age twenty-three, with less than a high school education and no formal training in art, Barthé was admitted to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and the Art Institute of Chicago, but opted for the latter.

From 1924 to 1928, Barthe studied painting and drawing at the Art Institute, while working as a waiter to help support himself. In addition to his classes, Barthe studied privately with the African American painter Archibald Motley, who was ten years older and also a graduate of the Art Institute. It was the first time Barthe had been allowed the opportunity to work with a Black model—an experience that would strongly influence his later work.

At the Art Institute, Barthe made his first experiments with sculpture. One of his teachers encouraged him to sculpt some heads in clay, claiming that it would give Barthe a feeling for a “third dimension” in his painting. The heads turned out so well that Barthe decided to cast them, and they were shown at an exhibition of work by Black artists, sponsored by the Chicago Women’s Club. This exhibition led to his first commission: busts of the artist Henry Tanner and Haitian leader Toussaint L’Ouverture.

The Great Depression, during the 1930s were Richmond Barthé’s most prolific years. He was one of the first African American artists who was able to support himself by creating art. He moved to New York City, following his graduation, which exposed Barthé to new experiences as he arrived in the city during the peak of the Harlem Renaissance. Barthé established his studio in Harlem in 1930 after winning the Julius Rosenwald Fund fellowship at his first solo exhibition at the Women’s City Club in Chicago. However, in 1931, he moved his studio in Harlem to Greenwich Village. Barthé once exclaimed: “I live downtown because it is much more convenient for my contacts from whom it is possible for me to make a living.”

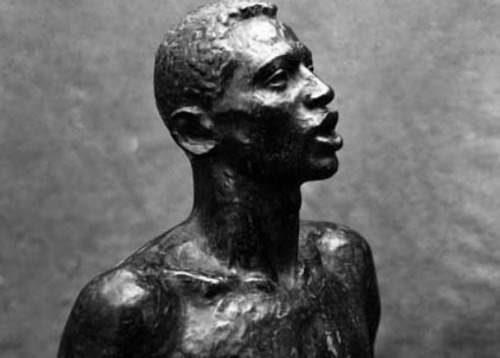

Living downtown provided him the opportunity to socialize not only among collectors but also among artists, dance performers, and actors. His remarkable visual memory permitted him to work without models, producing numerous representations of the human body in movement. During this time, Barthe went through an extremely productive period, creating more than 25 figures inspired by the Black experience, including African Girl, The Lindy Hop, and The Deviled Crab-Man.

While Barthe’s work was not generally political in nature, he occasionally created sculptures that reflected racial conflict in the United States. One example was a piece called Head of a Tortured Negro. Another, Mother and Son, shows a Black mother mourning over her dead son, who has rope marks on his neck, showing that he had been lynched.

In October 1933, a major body of Barthé’s work inaugurated the Caz Delbo Galleries at the Rockefeller Center in New York. That same year his works were also exhibited at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933. In the summer of 1934, Barthé went on a tour to Paris with Reverend Edward F. Murphy, a friend of Reverend Kane from New Orleans, who exchanged his first class ticket for two third class tickets to share with Barthé. This trip exposed Barthé to classical art, but also to performers such as Feral Benga and African American entertainer Josephine Baker, of whom he made portraits in 1935 and 1951, respectively. The trip also led to more exhibitions and commissions.

In March of 1939, Barthe’s largest exhibition, consisting of 18 bronzes, opened in New York City. This exhibition was also well received and helped him to win a Guggenheim fellowship in 1940, and again in 1941.

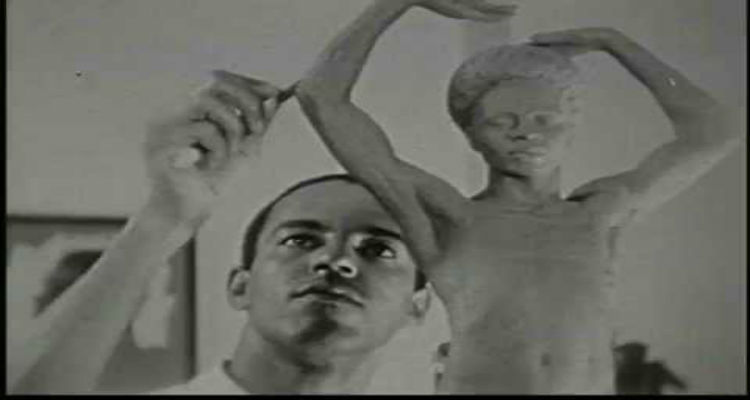

After World War II began in 1941, Barthe was in demand for U.S. war propaganda. The Office of War Information made a film of Barthe at work, which was shown in the United States and overseas. In 1942, he was awarded a prize at the “Artists for Victory” exhibition. While Barthe cooperated with these efforts, he understood exactly why he was suddenly receiving so much publicity. “This was the answer to Hitler and the Japanese who said that ’America talks democracy, but look at the American [Black],’” he was quoted as saying in A History of African-American Artists. “I think I have gotten more publicity than most whyte artists, most of it because I was a [Black].”

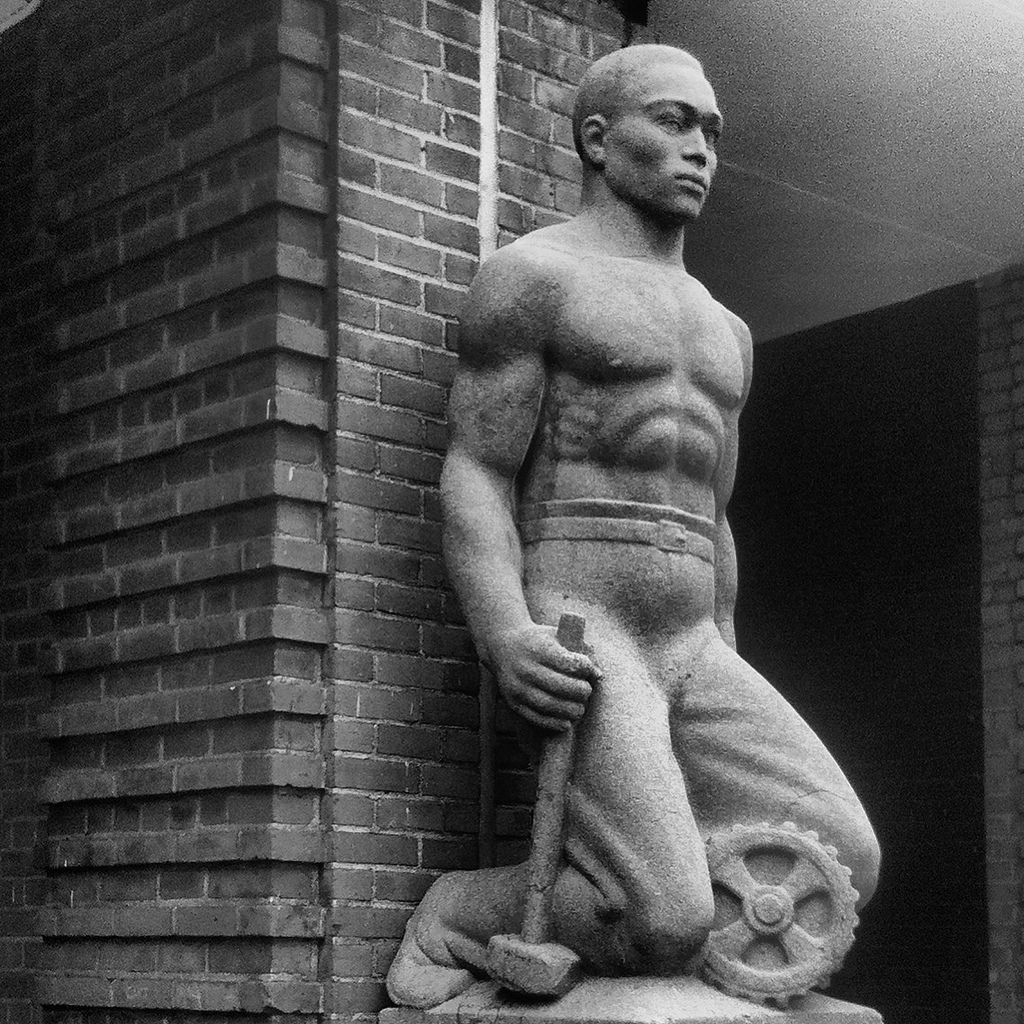

Throughout the 1940s, Barthe’s success continued. In 1943, one of his pieces, The Boxer, was purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 1945, he received a commission for a bust of Booker T. Washington for New York University’s Hall of Fame, leading to a pair of firsts: Washington was the first black person to have his bust in the Hall of Fame, and Barthe was the first black artist to be asked to create a bust. In 1945 Barthé became a member of the National Sculpture Society. In 1947, he travelled to Haiti, where he created monumental sculptures of leaders Toussaint L’Ouverture and General Dessalines. He also designed new Haitian coins, for which he was paid nearly $100,000.

Barthé moved to Jamaica in 1947, where he remained until the mid-1960s, when during the civil rights era in the United States, his work was once again in vogue. The mayor of his hometown invited him back and presented him with the key to the city. A reception was given for him at Tulane University in New Orleans, a city where Barthe once could not find an art school that would accept him. The publicity from these events, as well as an increase of tourists to Jamaica, brought a huge number of visitors to Barthe’s home. Feeling overwhelmed by crowds, he then moved to Europe, and spent the next five years in Switzerland, Spain, and Italy.

In 1977, Barthe returned to the United States, settling in Pasadena, California, near a sister in San Francisco, where he began working on his memoirs. By this time, he was elderly and impoverished. Having lived for so many years outside the United States and never having held a salaried job, Barthe was ineligible for Social Security benefits. It was a cruel twist of fate for the artist whose sculpture of an eagle stood in front of Washington’s Social Security Building. Meanwhile, Barthe’s work continued to be exhibited occasionally. In 1981, the Museum of African American Art in Santa Monica, California, showed his work as part of the special exhibition “Afro-American Art.” However, Barthe was no longer capable of earning enough money to support himself.

While living in Pasadena, Barthe met an unlikely advocate, the actor James Garner, who was then working on the television series The Rockford Files. The two became close friends. Realizing how desperate Barthe’s situation was, Garner paid his rent and medical bills. Garner copyrighted Barthé’s artwork, hired a biographer to organize and document his work, and established the Richmond Barthe Trust. To show his appreciation, Barthe modeled a bust of Garner, which is believed to be his last sculpture.

After a few years of illness, Barthe died on March 6, 1989, at the age of 88.

Richmond Barthe’s sculptures have been collected by the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Smithsonian Institution, as well as many other museums and universities. His most famous public works include an eagle that stands in front of the Social Security Building in Washington, DC, and a 40-foot statue of Haitian revolutionary Jean Jacques Dessalines, which he created for the city of Port-au-Prince. Barthe also designed several Haitian coins that are still in use.

Source:

http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Richmond_Barthe.aspx

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richmond_Barth%C3%A9

2 comments

The mostly untold history!

Thank you. Enjoyed reading about Richmond Barthe.. A Distinguished American Sculptor. The work shown is remarkable…