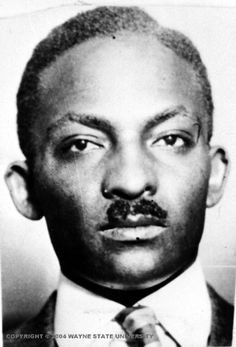

Ossian Sweet was an African American physician in Detroit, Michigan, noted for his armed self-defense in 1925 of his newly purchased home in a whyte neighborhood against a mob trying to force him out. He, his family and friends, who had helped defend his home, were acquitted by an all-whyte jury of murder charges in what came to be known as the Sweet Trials.

Sweet was born the second son to Henry Sweet and Dora Devaughn in Bartow, Florida, eight days before the death of his oldest brother Oscar. The Sweets had a total of ten children and lived in a small farmhouse, on the little money they could earn through their farm. As Sweet later told in 1925 at his murder trial, when he was a five-year-old boy, he witnessed the lynching of a Black male teenager Fred Rochelle. Rochelle, captured by Black males and turned over to the sheriff, admitted to attacking and murdering a whyte female, 26-year-old Rena Smith Taggart, with a butcher knife. According to Sweet’s account, he was out alone at night and a mile or more from his home, where he watched from the bushes as Rochelle was burned at the stake. Sweet recounted it with frightening specificity: the smell of the kerosene, Rochelle’s screams as he was engulfed in flames, the crowd’s picking off pieces of charred flesh to take home as souvenirs.

In September 1909, Sweet left Florida at age thirteen. His parents sent him to Wilberforce University in Xenia, Ohio; it was the first African-American college to be owned and operated by African-American. Sweet attended Wilberforce for eight years; the first four were spent in prep-school studying Latin, history, mathematics, English, music, drawing, philosophy, social and introductory science and foreign language (probably French) to prepare for college. He earned a bachelor of science at the age of twenty-five. He had worked shoveling snow, stoking furnaces, washing dirty dishes, waiting tables, and carting luggage up hotel stairs to pay the US$118 for his tuition and books. After Wilberforce, he attended Howard University in Washington, D.C., where he earned his medical accreditation.

Sweet arrived in Detroit in the late summer of 1921. He encountered difficulty finding work at a hospital due to racism, but working as a waiter at Detroit restaurants helped him see the need for medical care among residents in Black Bottom. He gave US$100 to a pharmacy, Palace Drugs, in exchange for office space. His first client, Elizabeth Riley, feared she had contracted tetanus because her jaw grew stiff. Sweet was able to diagnose that it was not an infection, but rather simply a dislocated jaw. He reset the bone, and Riley told friends in the neighborhood about his practice and his list of patients grew.

Sweet married Gladys Mitchell in 1922. She was born in Pittsburgh and had been raised in Detroit, a few miles north of Garland. She came from a prominent middle-class Black family. Recognizing a need for further medical training, Sweet left his practice in 1923 to study in Vienna and Paris. Although he did not complete a degree there, Sweet attended lectures by noted physicians and scientists, including Madame Curie.

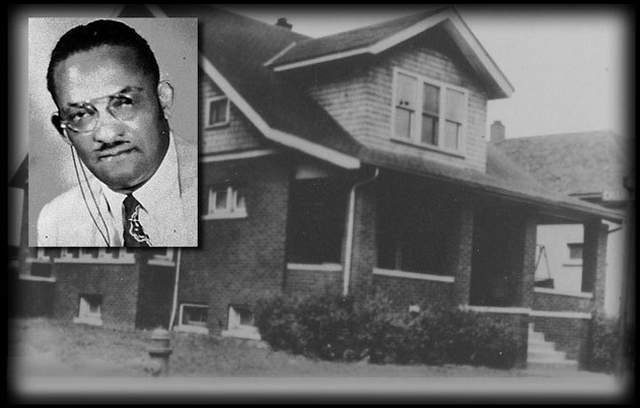

By June 21, 1924, the Sweets returned to Detroit. Sweet became affiliated with Dunbar Hospital, Detroit’s first black hospital. Having saved enough money, he moved his family in 1925 from his wife’s parents home in an all-whyte neighborhood, to 2905 Garland Street, another all-whyte neighborhood at Garland and Charlevoix. On June 7, 1925, the Sweets bought the house for US$18,500, about US$6,000 more than the house’s fair market value.

Sweet knew friends and acquaintances who had suffered attacks after buying houses in whyte neighborhoods. The social volatility of the time resulted in the formation of the Waterworks Park Improvement Association; it was based on opposition to Blacks moving into formerly all-whyte neighborhoods. Working-class whytes who lived in the neighborhood and made less money than Sweet resented his success.

Although Sweet originally planned to move his family into the new home in July, he postponed the move for two months in the hopes that racial tensions might ease. They didn’t.

On July 12, 1925, the Detroit Free Press carried a paid announcement:

To maintain the high standard of the residential district between Jefferson and Mack Avenues, a meeting has been called by the Waterworks Improvement Association for Thursday night in the Howe School Auditorium. Men and women of the district, which includes Cadillac, Hurburt, Garland, St. Clair, and Harding Avenues, are asked to attend in self-defense.

Despite being aware of the danger, Sweet decided to move his family into his Garland Avenue home on September 8. Ossian Sweet explained his decision to his brother: “I have to die like a man or live a coward.” Before moving in, Sweet prepared himself for the mob he expected to face. He bought nine guns and enough ammunition for all of them. He notified Detroit police of his planned move and asked for protection. He left his infant daughter at his wife’s mother’s home. Finally, he arranged to have his younger brothers, Henry and Otis, as well as some of their friends, join him and his wife Gladys for their first perilous night on Garland Avenue.

Police inspector Norton Schuknecht and a detail of officers had been placed outside the Sweet’s house to keep the peace, and protect him and his wife from any angry neighbors. When a hostile crowd formed for the second consecutive night in front of his home, Sweet felt that “somewhere out there, standing among the women and children, lounging on the porches, lurking in the alleys were the men who would incite the crowd to violence”. As the crowd grew restless some, possibly children or teenagers, threw stones at the house, eventually breaking an upstairs window. Several of Sweet’s friends were waiting upstairs, armed with guns that Sweet had purchased prior to moving in. Shots were fired from upstairs, hitting two men. One of them, Eric Houghberg was wounded in the leg. The other man, Leon Breiner, was killed.

Six policeman (who had been present at the house at the time of the shooting) entered the Sweet home, flung up all the shades, turned on all the lights, and arrested the eleven occupants. At police headquarters, the Sweets and their house guests were told for the first time that a man had been killed and a boy wounded. Each of the arrested persons was interviewed separately. They gave wildly different accounts of events. Some claimed to have been sleeping at the time of the shooting; one claimed to have been taking a bath. Ossian Sweet admitted having distributed a gun to each male occupant, while some of those interviewed denied any knowledge of guns. At about 3:30 A.M., an assistant prosecutor informed them that he planned to recommend first degree murder warrants against all eleven.

On September 16, at a preliminary hearing, Judge John Faust denied bail for all defendants.

When word of the trial reached James Weldon Johnson, general secretary of the NAACP, Johnson correctly predicted that this case could affect the civil rights struggle for African Americans. The NAACP sent Walter White, its assistant secretary, to Michigan on a fact-finding mission. After completing his assignment, White returned to New York where he met with Arthur Garfield Hays, a noted civil rights attorney, and Clarence Darrow, the most famous defense attorney of the time, and urged them to take the Sweet case. The Sweet trial was one of three main trials the NAACP supported in this year.

The State would call seventy witnesses in the Sweet trial. Most would testify that the crowd outside the Sweet home was small and orderly prior to the shooting. Many said it was “curiosity” that had brought them to the corner of Garland and Charlevoix. Some, such as neighbor Ray Dove, admitted on cross-examination that they didn’t “believe in the mixing of blacks and whites” and objected to the Sweets living in their new home. One witness (Edward Weltlauffer) admitted to hearing “cracking of glass” one minute before the firing. A police sergeant testified that he “talked to Dr. Sweet the morning before the shooting” and informed him that five men had been sent to his house to “protect the property.” Patrolmen Frank Gill testified that he saw two black men firing from the back porch of the Sweet home in different directions. Florence Ware said she saw “ten or so” shots come from the upper bedroom.

Beginning with their first witness, Alonzo Smith, a Black passenger in a car that had been attacked by the mob as it passed through the Garland Avenue district, Darrow and Hays tried to paint a very different picture of the scene around the Sweet home on September 9. Smith described people in the crowd he estimated at one thousand yelling, “Here’s a nigger now. Kill him. He’s going to the Sweets.” Other defense witnesses testified that they saw persons in a large crowd throwing stones at the Sweet home.

Sweet provided a riveting account of the events around 8:30 on September 9:

“We were playing cards; it was about eight o’clock when something hit the roof of the house. Somebody went to the window and then I heard the remark, “The people, the people.” I ran out to the kitchen where my wife was. There were several lights burning. I turned them out and opened the door. I heard someone yell, “Go and raise hell in front, I’m going back. I was frightened, and after getting a gun, ran upstairs. Stones kept hitting our house intermittently. I threw myself on the bed and lay there a short while. Perhaps fifteen minutes, when a stone came through the window. Part of the glass hit me. Pandemonium–I guess that’s the best way of describing it–broke loose. Everyone was running from room to room. There was a general uproar. Somebody yelled, “There’s someone coming!” They said, “That’s your brother.” A car had pulled up to the curb. My brother and Mr. Davis got out. The mob yelled, “Here’s niggers! Get them, get them!” As they rushed in, the mob surged forward fifteen or twenty feet. It looked like a human sea. Stones kept coming faster. I ran downstairs. Another window was smashed. Then one shot. Then eight or ten from upstairs; then it was all over….”

Sweets was asked why his courtroom testimony differed from that given to police on the night of his arrest. “I am under oath now,” Sweet answered. “I was very excited then and afraid that what I said might be misinterpreted.”

The jury found it difficult to reach a verdict in the case. The judge dismissed the jury and declared a mistrial. According to reports, seven of the jurors had favored conviction (for manslaughter) for Ossian and Henry Sweet, five favored acquittal. For the other defendants, the vote was ten to two in favor of acquittal.

After a second trial, Sweet was acquitted. However, both Gladys and her daughter, Iva, were found to have contracted tuberculosis. Gladys believed she contracted it while in jail. Two months after her second birthday, Iva died. During the two years following the loss of their daughter, Gladys’ illness drove them apart. He returned to the apartment near Dunbar Memorial, and she went to Tucson, Arizona, in order to benefit from the drier climate.

By mid-1928, Sweet finally regained possession of the bungalow, which had not been lived in since the shooting. A few months after Gladys returned home, she died of TB, at the age of twenty-seven. After her death, Sweet bought the Garafalo’s Drugstore. In 1929, he left his practice to run a hospital in the heart of the ghetto. He would eventually run a few of these small hospitals, but none ever flourished. As he began to approach the age of fifty, Sweet started to buy land in East Bartow, as his father had. In 1930, he decided to run for the presidency of the NAACP branch in Detroit, but lost by a wide margin. In the summer of 1939, Ossian realized that his brother had also contracted tuberculosis; six months later, the brother died.

By this point, Ossian’s finances had failed him. It took him until 1950 to pay off the land contract, and he assumed full ownership of the bungalow. He faced too much debt after that. Sweet sold the house in April 1958, to another black family. He transformed what had been his office above Garafalo’s Drugstore into an apartment. Around this time, Sweet’s physical and mental health began to decline; he had put on weight and had slowed in his motions. On March 20, 1960, he went into his bedroom and killed himself with a shot to the head.

Source:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ossian_Sweet