“As the black spot passed over the sun, so shall the Blacks pass over the earth.” – Nat Turner

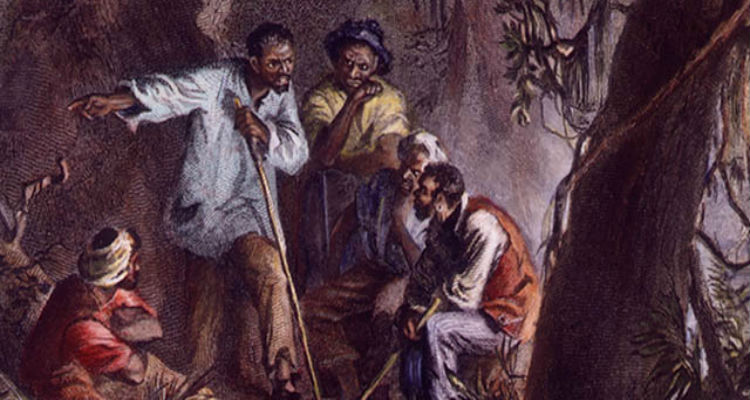

[dropcap size=small]O[/dropcap]n Sunday, 21 August 1831, six enslaved African American men – Henry, Hank or Hercules, Nelson, Sam, Will and Jack – met up in the woods, “for what is called in the Northern States a picnic and in the Southern a barbecue.” They brought a pig and some brandy, which gave the appearance of just a friendly get-together. However, four of men had been already initiated into a conspiracy. The group had been together from twelve to three o’clock, ‘when a seventh man joined them,—a short, stout, powerfully built person, of dark complexion and strongly-marked African features, but with a face full of expression and resolution. This was Nat Turner.’

When he came to the barbecue and found six men rather than four, his first question to the intruders was, How they came thither? To this Will answered that his life was worth no more than the others, and “his liberty was as dear to him.” Jack was known to be entirely under Hark’s influence. Eleven hours they remained there, discussing what was to become one of the largest Maafa (slavery) uprisings ever to take place in the United States. Two things were decided upon: to begin their work that night, and to begin it with a massacre so swift and irresistible as to create in a few days more terror than many battles, and so spare the need of future bloodshed. “It was agreed that we should commence at home, on that night, and, until we had armed and equipped ourselves and gained sufficient force, neither age nor sex was to be spared: which was invariably adhered to.”

Their plan was to move systematically from plantation to plantation in Southampton and kill all whyte people connected to the Maafa, including men, women, and children. At 2:00 a.m. on August 22, Turner and his six men killed the entire family of John Travis, Turner’s new enslaver. During the next twenty-four hours, Turner and his fellow warriors moved throughout the county to eleven different plantations, killing fifty-five people and inspiring fifty or sixty enslaved men to join their ranks.

Writing about the event thirty years later, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, an ardent abolitionist and soon-to-be colonel of the Union’s first Black regiment, wrote:

“Swift and stealthy as Indians, the Black men passed from house to house,–not pausing, not hesitating… In one thing they were humaner than Indians or than [whyte] men fighting against Indians,–there was no gratuitous outrage beyond the death-blow itself, no insult, no mutilation; but in every house they entered, that blow fell on man, woman, and child,–nothing that had a [pale] skin was spared. From every house they took arms and ammunition, and from a few, money; on every plantation they found recruits… The troop increased from house to house,–first to fifteen, then to forty, then to sixty. Some were armed with muskets, some with axes, some with scythes; some came on their [enslavers’] horses. As the numbers increased, they could be divided, and the awful work was carried on more rapidly still. The plan then was for an advanced guard of horsemen to approach each house at a gallop, and surround it till the others came up.”

The revolutionaires then moved on to the town of Jerusalem with the intention of destroying the town and killing all the inhabitants. But before they could reach their destination, they were stopped by a heavily armed whyte militia. The Governor had called about three thousand militiamen to put down the uprising. Seeing that they were greatly outnumbered, they disbanded, and many fled into the woods and swamps.

The whyte militia hunted down and soon captured or killed the men who had participated in the “rising”, except for Nat Turner.

The war for freedom was by no means a spontaneous or unmediated event.

As a child, Turner displayed a keen intelligence and was encouraged by his enslaver, Benjamin Turner, to read and study the Bible. Turner felt from his early years that he was “intended for some great purpose,” certain that one day he would be a prophet. (His father, it is believed, successfully escaped from his enslavers and the Maafa when he was very young; his name is unknown.) Turner studied the Old Testament, committing long passages to memory and heeding the words of the prophets. Working in the fields, he heard a voice call to him and became convinced that he had been chosen to carry out a divine mission. As he later recalled, “Having soon discovered to be great, I must appear so.” He cloaked himself in mystery, avoided fraternizing, abstained from alcohol, and devoted long periods to fasting. In cabins, fields and hush harbors (secluded parts of plantations where bondpeople would gather to worship out of sight of their enslavers), he began to exhort his fellow Atlantians (enslaved Blacks), promising them that something big would happen one day.

Then came the visions: black and whyte spirits engaged in battle; the Christian savior with arms outstretched; drops of blood on corn; leaves with hieroglyphic characters and numbers. Finally he understood the meaning of the signs: “The savior was about to lay down the yoke he had borne for the sins of men, and the great day of judgment was at hand.” It was just a matter of time.

In 1826 or 1827, Turner selected 20 trusted men. In May 1828, he experienced a vision of a serpent. In February 1831, he witnessed an eclipse of the sun. Then on August 13, 1831, the final signal was revealed to him: a second “black spot” on the sun. He told his followers, “As the black spot passed over the sun, so shall the blacks pass over the earth.” Some accounts also state that atmospheric interference (which could have been debris from the recent eruption of Mount Saint Helens) made the sun appear a rich bluish-green and Turner interpreted this as the final sign.

For two months after his rising, Turner hid in the woods of Southampton County. When he was finally captured, he was tried and convicted. Turner professed no regrets for his actions. He was hanged on November 11 and his body skinned.

Fifty-four other men were executed by the state. In addition, to terrorize the local African American population, some of the militia decapitated about fifteen of the captured warriors and put their heads on stakes. Then, as fear spread through the whyte population, whyte mobs turned on blacks who had played no role in the uprising.

An estimated two to three hundred African Americans, most of whom were not connected to the rebellion, were murdered by whyte mobs.

In the aftermath of the rebellion, the state legislature of Virginia considered abolishing slavery, but instead voted to tighten the laws restricting blacks’ freedom in hopes of preventing any further uprising.

In nearby North Carolina, several enslaved blacks were accused — falsely — of being involved in Turner’s vision for freedom and executed. Rumors spread that the bondpeople in North Carolina were plotting their own uprising, and whyte mobs murdered a number of enslaved men, while others were arrested, tried, and a few executed. North Carolina, like Virginia, passed new legislation further restricting the rights of both enslaved people and free blacks. The legislature made it illegal for enslaved people to preach, to be “insolent” to whyte people, to carry a gun, to hunt in the woods, to cohabitate with a free black or whyte person, to own any type of livestock. These new codes also forbade whyte people from teaching an enslaved person to read.

Sources:

http://www.pbs.org/godinamerica/people/nat-turner.html

http://thisdayinalternatehistory.blogspot.ca/2010/08/august-21-1831-nat-turner-begins-his.html

http://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2013/08/on-this-day-in-1831-a-bloody-uprising-in-the-virginia-countryside/278905/