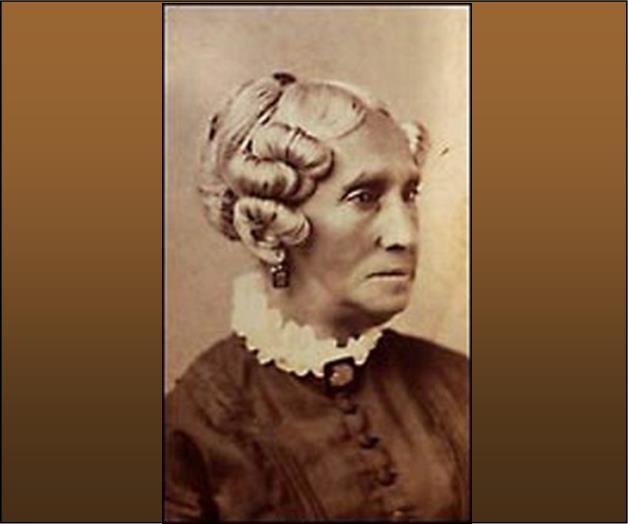

Maria W. Stewart, essayist, teacher, and political activist, is thought to be the first woman in America and the first African-American woman to make public lectures. Stewart is known for four powerful speeches, delivered in Boston in the early 1830s—a time when no woman, Black or whyte, dared to address an audience from a public platform.

Born Maria Miller in Hartford, Connecticut in 1803, Stewart’s parents’ first names and occupations are not known. Stewart was orphaned by age five and became an indentured servant, serving a clergyman until she was fifteen. She also attended Connecticut Sabbath schools and taught herself to read and write.

In 1826 Miller married James W. Stewart. Her husband, a shipping agent, had served in the War of 1812 and had spent some time in England as a prisoner of war. With her marriage, she became part of Boston’s small free black middle class and soon became involved in some of its institutions including the Massachusetts General Colored Association, which worked for immediate abolition of slavery. When James W. Stewart died in 1829, the white executors of her husband’s will took her inheritance through legal actions, leaving her penniless.

Soon after Boston abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison established his newspaper, The Liberator, in January 1831, he specifically called for black women to write in its pages. Stewart was the first woman to respond, and, by the summer of 1831, he published her first essay, Religion and the Pure Principles of Morality, as a pamphlet. Building on that notoriety, Stewart launched her public speaking career at a time when women were banned from speaking in public, especially to audiences that included men.

In her first address, in April 1832, Stewart spoke before a women-only audience at the African American Female Intelligence Society, an institution founded by the free black community of Boston. Speaking to that audience, she used the Bible to defend her right to speak and lectured on religion, justice, and equality.

On September 21, 1832, Stewart delivered a second lecture, this time to an audience that also included men. She spoke at Franklin Hall, the site of the New England Anti-Slavery Society meetings. She called for civil rights for northern blacks and questioned emigration to Africa, which was then promoted by the American Colonization Society.

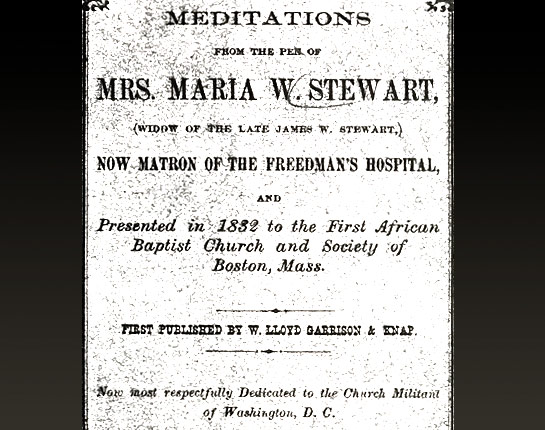

Garrison published both speeches in the pages of The Liberator. He published the text of her speeches there, putting them into the Ladies Department. He also published a second pamphlet of her writings as Meditations from the Pen of Mrs. Maria W. Stewart.

On February 27, 1833, Maria Stewart delivered her third public lecture, “African Rights and Liberty,” at the African Masonic Hall. Her fourth and final Boston lecture was a “Farewell Address” on September 21, 1833, when she addressed the negative reaction that her public speaking had provoked, expressing both her dismay at having little effect, and her sense of divine call to speak publicly. Then she moved to New York.

In 1835, Garrison published a pamphlet with her four speeches plus some essays and poems, titling it Productions of Mrs. Maria W. Stewart. These likely inspired other women to begin public speaking, and such actions became more common for Maria Stewart’s ground-breaking.

In New York, Stewart remained an activist, attending the 1837 Women’s Anti-slavery Convention. A strong advocate for literacy and for educational opportunities for African Americans and women, she supported herself teaching in public schools in Manhattan and Brooklyn, becoming an assistant to the principle of the Williamsburg School. She was also active there in a black women’s literary group. She also supported Frederick Douglass’ newspaper, The North Star, but did not write for it.

Maria Stewart moved to Baltimore in 1852 or 1853, apparently after losing her teaching position in New York. There, she taught privately. In 1861, she moved to Washington, DC, where she taught school again during the Civil War. One of her new friends was Elizabeth Keckley, seamstress to First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln and soon to publish a book of memoirs.

While continuing her teaching, she was also appointed to head housekeeping at the Freedman’s Hospital and Asylum in the 1870s. A predecessor in this position was Sojourner Truth. The hospital had become a haven for former slaves who came to Washington. Stewart also founded a neighborhood Sunday school.

In 1878, Maria Stewart discovered that a new law made her eligible for a widow’s pension, for her husband’s service in the Navy in the War of 1812. She used the eight dollars a month, including some retroactive payments, to republish Meditations from the Pen of Mrs. Maria W. Stewart, adding material about her life during the Civil War and also adding some letters from Garrison and others.

The book, which appeared in 1879, was introduced by supporting letters from Garrison and others. It also included new material: the autobiographical essay “Sufferings During the War,” and a preface in which she once more called for an end to tyranny and oppression.

Shortly after the book’s publication in December of 1879, Stewart died at the Freedman’s Hospital at the age of 76. Her obituary in The People’s Advocate, a Washington-area black newspaper, acknowledged that Stewart had struggled for years with little recognition: “Few, very few know of the remarkable career of this woman whose life has just drawn to a close. For half a century she was engaged in the work of elevating her race by lectures, teaching, and various missionary and benevolent labors.” Stewart was buried in Graceland Cemetery in Washington on December 17, 1879—50 years to the day after her husband’s death.

Sources:

http://www.blackpast.org/aah/stewart-maria-miller-1803-1879#sthash.rNGKbHz0.dpuf

http://womenshistory.about.com/od/slaveryto1863/a/Maria-W-Stewart.htm

http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Maria_W._Stewart.aspx