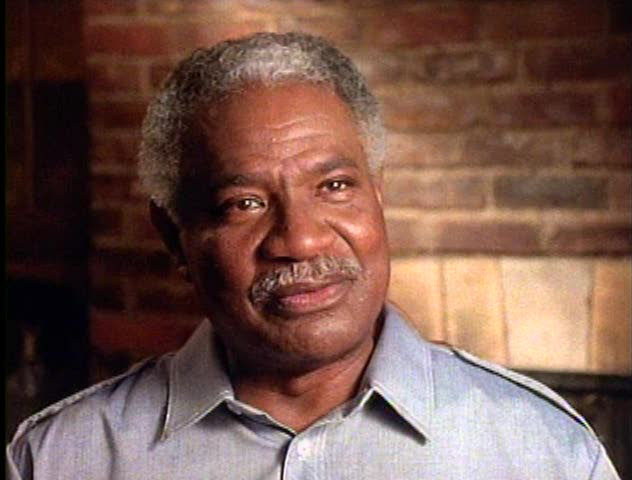

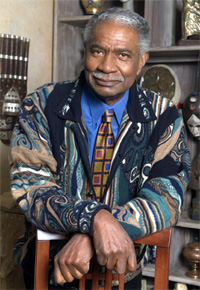

Ossie Davis was one of the most recognized and influential African American performers and activists of the late twentieth century. The acclaimed actor, director, producer, screenwriter, playwright and civil rights activist, along with his wife of fifty-six years, Ruby Dee, Davis received numerous awards, including the National Medal of Arts in 1995 and a Kennedy Center Honor in 2004. The couple, who appeared in numerous productions together, was widely credited with furthering opportunities on stage and screen for subsequent generations of black artists.

Born Raiford Chatman Davis on December 18, 1917, in the Clinch County town of Cogdell, where his father was a railroad engineer. The nickname “Ossie” came from his mother’s pronunciation of his initials, R.C. Davis attended Howard University in Washington, D.C., but dropped out after three years to pursue a writing career and to study drama with the Rose McClendon Players in Harlem. During the next few years he found work doing various menial jobs. In 1942, soon after the United States entered World War II (1941-45), Davis enlisted in the army at Fort Benning. He served in Liberia at the Twenty-fifth Station Hospital and was honorably discharged in 1945. While in the army he wrote and acted in shows for the troops.

When the war was over, Davis made his Broadway debut in 1946 in Jeb. During the play’s relatively short run, he was attracted to a fellow cast member, Ruby Dee, from Cleveland, Ohio. The couple married on December 9, 1948, and had three children, one of whom is the actor Guy Davis. During the 1950s Davis began his film and television career with sporadic roles. His first on-screen appearance was in the movie No Way Out (1950), in which Sidney Poitier also made his screen debut.

During the 1960s, as American television began to feature more African American actors, Davis found himself getting more roles, including parts in the television movies Seven Times Monday (1962) and The Outsider (1967), as well as regular guest appearances on The Defenders, a series that aired from 1961 to 1965. While his television career was beginning to boom, Davis’s film career flourished as well. He worked with such notable directors as Otto Preminger in The Cardinal (1963) and Sidney Lumet in The Hill (1965) and appeared in a number of other films, including Shock Treatment (1964) and A Man Called Adam (1966).

Davis’s theater career also began to solidify in the 1960s as a playwright and director. He wrote the Broadway musical Purlie Victorious, a satire on Black and whyte stereotypes in the South, in 1961, which proved to be a success, and later turned the musical into the screenplay for the film Gone Are the Days (1963), in which he played a lead role. Among the other plays Davis wrote were Alice in Wonder, a drama in one act (1952). Set in the 1950s during McCarthyism, an African American television actor is asked to testify before a congressional committee. A year later Alice was expanded into a three-act version entitled The Big Deal.

Curtain Call, Mr. Aldridge Sir (1963) is a dramatic reading in one act highlighting the life and career of Ira Aldridge, the eminent black Shakespearean actor of the early 19th century. The University of California/Santa Barbara produced it with Davis and Dee in the cast in the summer 1968). Escape to Freedom (1976) is a full-length historical play for children about Frederick Douglass, the famous abolitionist and orator. It opened at Town Hall in New York City (March 1976).

Davis also wrote Langston: A Play in 1982, a full-length biographical drama about playwright-poet-short storywriter Langston Hughes. His play, Bingo (1985) is a full-length musical based on William Brashler’s book, Bingo Long’s Traveling All Stars and Motor Kings (made into a film in 1976), about the rise and fall of a black baseball team of the 1930s. One of Davis’s first plays, Montgomery Footprints (1956), was a one-act drama about the Rosa Parks incident that spearheaded the bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, led by Dr. Martin Luther King.

In addition to his creative endeavors during the 1960s, Davis, along with Dee, was active in the civil rights movement. The two were masters of ceremonies for the 1963 March on Washington, where Davis announced the death of W. E. B. Du Bois, who died in Ghana on August 27, 1963, the night before the march began. Following the march, the couple continued to work closely with Martin Luther King Jr. Davis raised money for the Freedom Riders when they were arrested in the South for violating segregation laws, and he sued in federal court to ensure voting rights for African Americans. He also delivered the eulogy at the funeral of Malcolm X and spoke at a 1968 memorial service in New York City for King.

During the 1970s Davis added directing, writing, and producing to his list of professional accomplishments. In 1970 he directed an adaptation of the Chester Himes novel Cotton Comes to Harlem, the story of two unorthodox African American policemen, and followed this debut with Countdown at Kusini (1976), in which he also starred with Dee. Davis received writing credits for both films. His production company, Third World Cinema, was founded in the 1970s to assist budding African American and Puerto Rican filmmakers, and in 1976 Davis published his first play for children, Escape to Freedom: A Play about Young Frederick Douglass, which he later followed with Langston, a Play (1982) and Just Like Martin (1992).

Davis continued to make numerous television appearances, including roles in the miniseries Roots: The Next Generation (1979) and the 1990s situation comedy Evening Shade, starring Burt Reynolds. He has had consistent film work during the 1990s and frequently collaborated with writer and director Spike Lee, appearing in five of Lee’s films including Do The Right Thing in 1990. In 1998, on the occasion of their fiftieth wedding anniversary, Davis and Dee published their autobiography, In This Life Together.

Both Davis and Dee also won many awards. In 1995 they were awarded the National Medal of Arts by U.S. president Bill Clinton. They were inducted into the NAACP Image Award Hall of Fame in 1996, and in 2000 the Screen Actors Guild bestowed their highest award, the Life Achievement Award, on the couple. In 2004 Davis and Dee were both honored by the Kennedy Center in recognition of their “lifetime contributions to American culture through the performing arts.”

Davis died on February 4, 2005, in Miami Beach, Florida, where he was working on a film. In 2007 the audio version of With Ossie and Ruby, recorded by Davis and Dee and released after his death, won a Grammy Award for best spoken word album.

Sources:

http://www.blackpast.org/aah/davis-ossie-1917-2005#sthash.biPrnK8s.dpuf

http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/arts-culture/ossie-davis-1917-2005