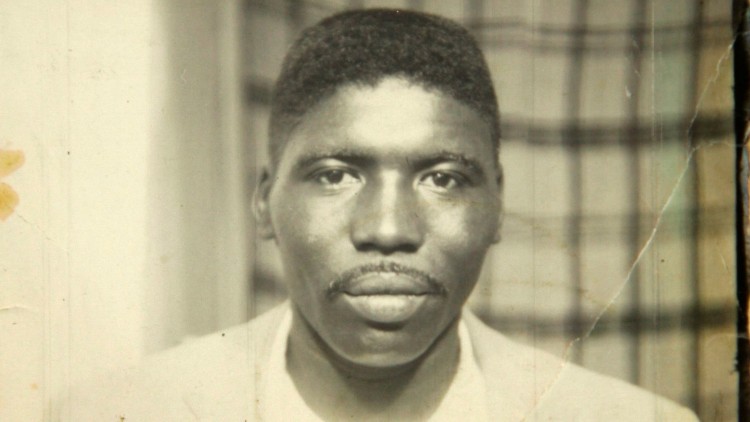

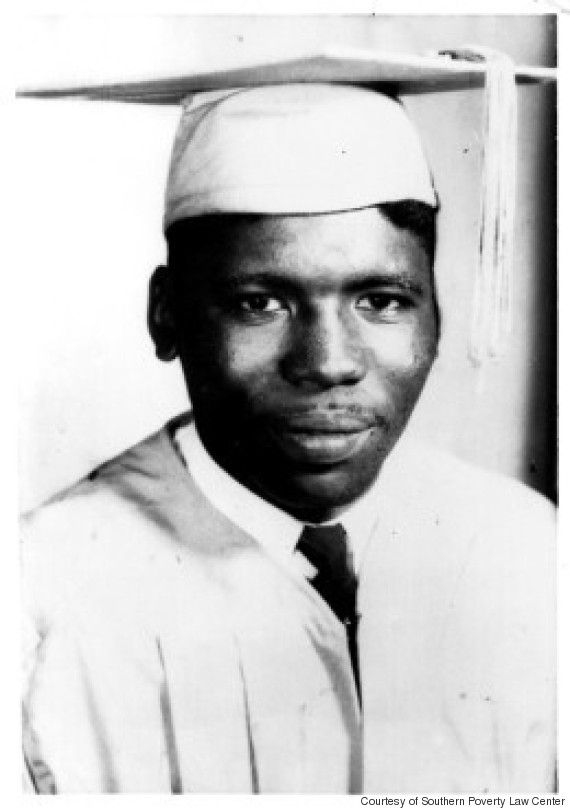

Activist Jimmie Lee Jackson is remembered for his tragic death at 26 years old at the hands of an Alabama state trooper during a small protest as part of the larger civil rights movement in Marion, Perry County. His death was eulogized by Martin Luther King Jr., and other movement leaders called for a march from Selma to Montgomery to protest Jackson’s death and advocate for voting rights. That March 7 event ended prematurely with a violent response from law enforcement that quickly became known as “Bloody Sunday,” but it prompted federal lawmakers to pass the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Jimmie Lee Jackson was born on December 16th, 1938 in Marion, Alabama, a small town located near Selma. After fighting in the Vietnam War and spending time in Indiana, he returned to his hometown. There, he made about $6 a day as a laborer and woodcutter.

Throughout late 1963 and 1964, local black activists in Selma and nearby Marion campaigned for their right to vote. By the time Martin Luther King and the SCLC arrived in Selma on 2 January 1965 to support the campaign, Jackson had already attempted to register to vote several times. King chose to bring SCLC to the region because he was aware of the brutality of local law enforcement officials, led by the sheriff of Dallas County, James G. Clark. King thought that unprovoked and overwhelming violence by whites against nonviolent blacks would capture the attention of the nation and pressure Congress and President Lyndon Johnson to pass voting rights legislation.

On February 18, 1965, he was among more than 200 people participating in a night march in Marion. Before they had walked a block, they were confronted by state troopers and the police chief, who ordered them to disperse.

The marchers halted at the chief’s order, and suddenly all the streetlights on the square went out. A black minister at the head of the march knelt to pray and was struck on the head by a trooper. Other troopers began swinging their clubs, and the marchers panicked, running for cover.

Jackson and his mother huddled for safety in a café. When Jackson’s grandfather entered the café bloodied and beaten, the young man tried to take him to a hospital. But they were quickly shoved back by a crowd of club-swinging troopers and terrified marchers.

The troopers began knocking out the café lights with their clubs and beating people. Jackson saw a trooper strike his mother, and he lunged for the man. He was clubbed across the face and slammed him into a cigarette machine. Another trooper pulled his pistol and shot Jackson in the stomach. It was two hours before Jackson arrived at the hospital in Selma. He died eight days later.

Though hundreds had been beaten and jailed in Alabama for marching and carrying signs demanding the right to vote, Jimmie Lee Jackson was the first to be murdered.

A thousand people followed Jimmie Lee’s casket through a teaming rain to a local cemetery.

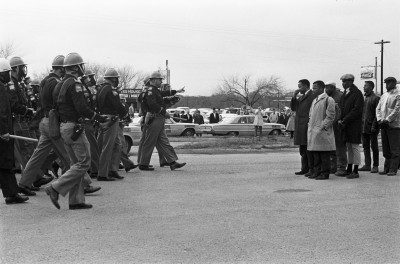

Four days later, several hundred marchers left Brown Chapel in Selma, formed a long column, two abreast to fit the narrow sidewalk, and began walking up the steep incline of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, which spans the Alabama River. Their goal was to walk the 54 miles to the state capitol in Montgomery to protest Jackson’s death and petition the governor and legislature to open the state’s voting rolls to all citizens.

They never made it across. Alabama State Troopers, again in riot gear, fired canisters of tear gas and charged into the marchers with clubs flailing. Though no one died, many suffered severe wounds. This time, however, the cameras were rolling. That night millions of Americans saw and heard what transpired on what came to be called “Bloody Sunday.”

That event spurred thousands of people to travel to Selma to join the protest. President Lyndon B. Johnson directed the U.S. Department of Justice to intervene, and later that month, with National Guard troops stationed along the route, civil rights supporters completed their march from Selma to Montgomery.

In August of that year, President Johnson signed into law the Voting Rights Act of 1965. With the power of the federal government now engaged, African-Americans began registering in Alabama and other states that had long prevented them from voting. Today, they constitute a formidable force at the polls and in local government in Perry County and other places where racists once used lawful and unlawful force to maintain their stranglehold on power.

The death of Jimmie Lee Jackson set in motion a train of events that stirred a lethargic nation and compelled once-reluctant politicians to use the power of federal law to ensure that every adult citizen could register and vote. Denied that birthright in life, Jimmie Lee Jackson by his death shamed politicians to take up a cause that many had long ignored, giving millions of his brothers and sisters, once voiceless, the right to determine who will hold office and the power to hold them to account for their deeds and misdeeds.

In March 2005, former trooper James Bonard Fowler admitted publicly for the first time to shooting Jackson, but maintained that he did so in self-defense, as he and Jackson wrestled for control of Fowler’s service revolver. On May 9, 2007, more than four decades after the killing of Jackson, a grand jury issued an indictment regarding his death. On May 10, the 73-year-old Fowler surrendered to authorities. He claimed that, as an Alabama state trooper charged with keeping the peace, he was forced to shoot Jackson in self-defense. Without regret or remorse, Fowler said he was only following orders. In November 2010, Fowler pleaded guilty to second-degree manslaughter and was sentenced to six months in jail, although he had been charged with murder originally.

Sources:

http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-2011#sthash.rw77VTre.dpuf

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/peter-j-ognibene/jimmie-lee-jackson-the-de_b_456870.html

http://www.biography.com/people/jimmie-lee-jackson-21402111#early-life

https://www.splcenter.org/what-we-do/civil-rights-memorial/civil-rights-martyrs/jimmie-lee-jackson