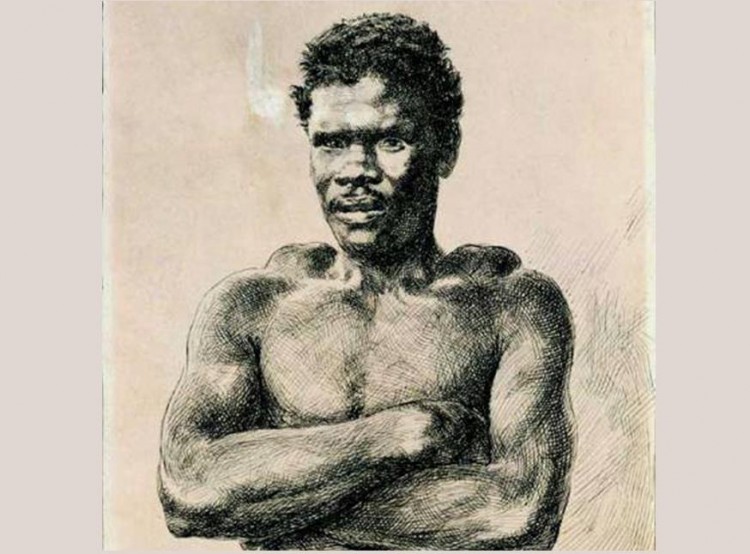

Thomas Fuller was an enslaved man who became known as the Virginia Calculator. Although illiterate he was able to perform the most difficult mathematical calculations. Late in his life, Fuller was discovered by antislavery campaigners and became a cause celebre on both sides of the Atlantic.

Fuller was born somewhere between the “Slave Coast” of West Africa (present-day Liberia) and the Kingdom of Dahomey (modern-day Benin). He was captured and sent to America in 1724 at the age of 14. Fuller was enslaved by Presley and Elizabeth Cox of Alexandria, Virginia. Both Fuller and the Coxes were illiterate. The Coxes enslaved 16 people and appeared to value Fuller the most, because of his unusual talent for solving complex math problems in his head. His talent was put to practical use, and he was employed in every phase of the management of their 232-acre plantation farm. For example, his enslavers would ask:

How many shingles for the new roof? How many poles and rails to enclose the meadow? How much corn to seed a designated field?

His answers were immediate, and always correct.

As the years passed, stories of his abilities became known throughout the Eastern seaboard.

In 1777, a Philadelphia Quaker and businessman, William Hartshorne, moved his family to Alexandria. Hartshorne and three other Quakers from Philadelphia came to meet Fuller to test his arithmetic feats. One of the visitors took notes and made calculations on paper, and the others fired questions at him. Fuller was seventy years old.

First question: How many seconds are there in a year and a half? In about two minutes came Tom Fuller’s reply — 47,304,000. Next question: How many seconds has a man lived who is seventy years, seventeen days and twelve hours old? Fuller’s answer — 2,210,500,800 — came in a minute and a half. “Objection,” called the recorder, who was busily multiplying on paper. He challenged Fuller’s answer as being too large. But Fuller explained that the man had missed the leap years.” By adding the seconds of the leap years, the recorder finally acknowledged the correctness of Fuller’s result.

The final question was proposed to Fuller: Suppose a farmer has six sows and each sow has six female pigs the first year, and they all increase in the same proportion each year. At the end of the eighth year, how many sows will the farmer have? The question was stated in such a way that Fuller misinterpreted it. However as soon as the statement was clarified, his lightning mind responded: 34, 588,806.

Filled with awe, the Philadelphians picked up their notes and took their leave. As they departed, one of the visitors remarked what a pity it was that this man had been denied an education. Fuller disagreed, stating that it was best that he had no learning, “for many learned men be great fools.”

Hartshorne’s colleagues returned to Philadelphia and immediately called on Dr. Benjamin Rush, one of the leading abolitionists of the day. Of their encounter with Fuller, they had written:

“He was gray-headed, and exhibited several other marks of the weakness of old age. He had worked hard upon a farm during the whole of life but had never been intemperate in the use of spirituous liquors. He spoke with great respect of his [enslavress], and mentioned in a particular manner his obligations to her for refusing to sell him, which she had been tempted to by offers of large sums of money from several persons. One of the gentlemen, Mr. Coates, having remarked in his presence that it was a pity he had not an education equal to his genius…”

Rush turned their report into a letter to the Abolitionist Society of Pennsylvania, from whence it was transmitted to the London Abolitionist Society. For a brief moment late in his life, Tom Fuller became a cause celebre on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean.

Present day thinking is that Fuller learned to calculate in Africa before he was kidnapped. Supporting evidence for this comes from a passage written by Thomas Clarkson in 1788 describing the purchase of African captives: “It is astonishing with what facility the African brokers reckon up the exchange of European goods for [captives]. One of these brokers has ten [captives] to sell, and for each of these he demands ten different articles. He reduces them immediately by the head to bars, coppers, ounces… and immediately strikes the balance. The European, on the other hand, takes his pen, and with great deliberation, and with all the advantage of arithmetic and letters, begin to estimate also. He is so unfortunate, as to make a mistake: but he no sooner errs, than he is detected by this man of inferior capacity, whom he can neither deceive in the name or quality of his goods, nor in the balance of his account.”

However, Fuller explained that his mathematical skill came from experimental applications around the farm such as counting the hairs in a cow’s tail or counting grains in bushels of wheat or flaxseed. He also figured out a new way of multiplying how far apart objects were, wading into complex astronomy-related computations, now carried out by computer.

In 1790 Tom Fuller died at the age of 80 years.

The Columbian Centinel, a Boston, Massachusetts newspaper noted in its obituary of Fuller: “Thus died… Tom, this self-taught arithmetician, this untutored Scholar! — Had his opportunities of improvement been equal to those of thousands of his fellow-men, neither the Royal Society of London, the Academy of Science at Paris, nor even Newton himself, need have been ashamed to acknowledge him a Brother in Science.”

Source:

https://www.csmonitor.com/1980/0212/021207.html/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Fuller_(mental_calculator)

https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/fuller-thomas-1710-1790/