“We are not there yet. Not yet Uhuru. Uhuru meaning freedom. We see it every day with our children at school. The trials and tribulation that they go through….with African Canadian young men not graduating. This is in 2014. We are not there yet. My work is for that. My work is for us to reach that Promised Land.”

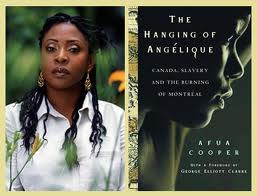

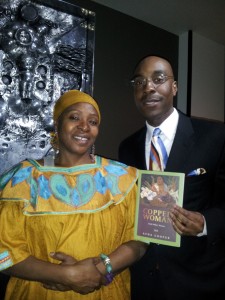

Dr. Cooper is considered one of the foremost experts in Black Canadian history and the author of The Hanging of Angélique: The Untold Story of Canadian Slavery and the Burning of Old Montréal which details the life and death of Marie-Joseph Angélique, a Portuguese-born Black enslaved woman who was hanged in Montréal in 1734 for allegedly setting fire to the city. The book was nominated in 2006 for the Governor General’s Literary Award for non-fiction.

In this exclusive interview Dr. Cooper shares profound insight on the often overlooked history of Black people in Canada as well as her own personal history.

Born November 8th, 1957 in Jamaica, Dr. Cooper grew up in the working class neighborhood of Rae Town and Franklin Town. There, as a young girl, she was drawn to the “street colleges” of the area. As she described:

“You would find men and women gathering at street corners, playing card games, playing dominoes, and talking politics. Often a lot this politics centered around Black people’s struggle. Black people struggling in Afrika, Black people struggling in Jamaica, Black people struggling in the United States.

As a young kid, my ears were always open to this and in my community were the Rasta people and they were very political and they were always talking about culture and history and ‘Black Man, you must know your history.’

I also grew up at a time, when I went to high school and even in my latter years of primary school, when the teachers were teaching aspects of Black history. My schools they taught about slavery, not in any great depth, because you know we’re 11 years old, but at the same time giving us the names of some of the slave heroes like Nanny and Tacky, so I think at that time we were very fortunate going to high school in the 70s there was a consciousness at the level of the senior educators, meaning people at the Ministry of Education who thought that Jamaican school kids need to learn about Afrikan history. In grade 8 we were doing the great kingdoms of West Afrika; I remember Ghana, Mali and Songhay, that’s what we did in grade 8 as part of our social studies curriculum.”

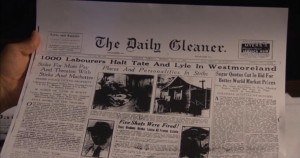

Dr. Cooper’s family was also a strong influence on her growing interest in history and culture particularly her grandmother, an engaging story teller, who would share more than the just the popular and traditional folktales such as the Anancy stories. Her grandmother would captivate the young Dr. Cooper with stories of Jamaica’s 1938 riots where sugar workers rose up against the government and several people were shot and killed by soldiers in Westmoreland and St-Thomas.

“…she would tell us those stories… How as a young woman she stood by her gate and she saw the Lorries, the trucks passing by with the soldiers and the guns… I was always fascinated by those stories of the colonial past and how Black people struggled and resisted degradation.”

Dr. Cooper’s aunt, who she believes may have been a Garveyite and who migrated to England and the United States in the 1950s, also would tell fascinating stories of the political meetings she attended as a young girl in Kingston, Jamaica about Blackness and Black freedom.

Marcus Garvey Garveyite family

“I just think I was very fortunate to have that context growing up and the stories that had a tremendous impact on my consciousness.”

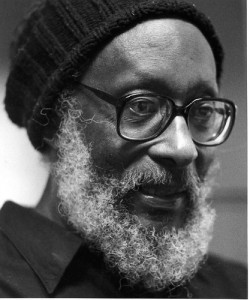

By the time Dr. Cooper entered high school in Jamaica, she was reading and being influenced by the work of the great Afrikan-Caribbean historian Walter Rodney and his book How Europe Underdeveloped Africa and Barbadian historian and poet Kamau Braithwaite.

Walter Rodney Kamau Braithwaite

Dr. Cooper would later attend teachers college and obtained a diploma in English studies and history and then taught after that for one year. However, the political violence in Jamaica in the 1980 elections resulting in over 1,000 deaths greatly disheartened her and forced Dr. Cooper to migrate to Canada at 22 years of age.

Dr. Cooper’s older sister lived in Toronto and had encouraged her to come to Canada due to the country’s need for teachers with the cultural competence to deal with the growing new wave of migrant students from the Caribbean in the city. However, her qualifications were not recognized so she was unable to find work. She decided to pursue higher education and enrolled in the University of Toronto where she took a B.A. in history and African studies eventually earning a PhD first in African history.

She also studied Caribbean history and Canadian history as complimentary areas focusing particularly on the study of women and gender and writing her thesis on West Afrika, Islam and women.

As she was preparing to travel to Sierra Leone in Afrika to do her field work, the civil war broke out in that country in 1993 causing her to cancel her plans and question her next moves.

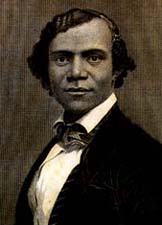

“‘What am I going to do?’ It was quite easy actually, my new decision, because I had done a Master’s degree in the history of education. I had done work on Black education in Ontario in the 19th century. So when I had to find a new thesis topic for my PhD, I basically revisited that research area which is Ontario, Black people, 19th century, Underground Railroad communities and looked at Henry Bibb who was a runaway fugitive slave from Kentucky; he came over to Ontario and started the 1st Black newspaper: The Voice of the Fugitive.”

Henry Bibb and the Voice of the Fugitives

This pivotal decision led Dr. Cooper in the direction of her current passion as one of the foremost experts of Afrikan-Canadian history.

Dr. Cooper’s PhD work in looking at the Black communities of 19th century Ontario developed into another field of study: The Maafa (slavery) of Black people in Canada before the Underground Railroad era.

“I had that background in slavery studies from studying the Trans-Atlantic slave trade as part of Afrikan history work and also as part of my Caribbean history work. I had this background in Trans-Atlantic slavery that touched three continents and several regions.”

Dr. Cooper’s great work in chronicling Afrikan Canadian history is reflected in her groundbreaking research on the history of Black people especially in Nova Scotia. In our interview, she would later elaborate on the fascinating connection between the Maroons of Jamaica and that eastern Canadian province.

“We have two men, two Afrikans in Annapolis Royal Nova Scotia in 1604. Two records of two men. One was an unnamed Afrikan man who died at Port Royal which is in Nova Scotia ….Then there was Mathieu Da Costa –the very intriguing Mathieu Da Costa who was also in the employ of sieur de Monts…Da Costa was listed as a translator, a linguist, an interpreter for the French and the local Indigenous communities, which in this case would be the Mic Mac people and perhaps the Abenaki and or the Malossi, but certainly the Mic Mac… (H)e spoke French, we also know he spoke Dutch, he spoke Portuguese, and local indigenous languages. That is tremendous. Mathieu Da Costa was a free man. He was not an enslaved man as far as we know. The first record we have, documents for an Afrikan, in this country, not just Nova Scotia, but this entire country is that of a free man who was at the service of the French colonial enterprise. It is a paradoxical story. I don’t know his thinking, but here he was furthering French colonization in the so-called New World, in this case, in Canada.

This story has multiple dimensions and one of the dimensions is that the Black presence, this Afrikan presence puts us first before the British, in terms of non-Native people.”

Mathieu Da Costa

Dr. Cooper believes this information radically changes the traditional account of the so-called founding fathers of Canada story replayed even today in Canadian history texts.

“Afrikans were here before the English (as in non-native people, non-Native communities). And yet that is so blatantly written out of history. But the fact of the matter is that Black people have a long an enduring presence in this country and we need to ponder that. We really need to ponder that and think of that because one of the functions of racist discourse is to write Black people out of Canadian history and position us as newcomers; That we started to come after the second World War and maybe even later… 1962, 1967 whenever… that our presence is a recent one and not a 400 year presence.”

The presence of Black people in Canadian history can also be seen in the presence of Jamaican Maroons in Nova Scotia in 1796.

“In 1796 about 600 Jamaican Maroons from Trelawny were exiled to Nova Scotia by the Jamaican colonial and the British imperial government. This was after the second Maroon war in which both sides –the Maroons and the British- came to a treaty. However, the British betrayed the treaty and the Maroons found themselves rounded up and put on ships. Nova Scotia was randomly chosen. There were talks of sending the Maroons to Belize and Bahamas and other places, but there were some transportation trips or transport ships that were leaving…for Nova Scotia from Jamaica and they said ‘Ah ha, we can send the Maroons to Nova Scotia because we really need to get rid of them.’

So the Maroon lands were stolen as soon as they left the island. They weren’t going to bring them back from Jamaica.

(The Maroons) were unbending even in Nova Scotia because the Nova Scotian government thought that they could bring the Maroons here and have them work for white people. The Maroons said, ‘No, no, no we’re not going to do that. We didn’t want to leave Jamaica. We are free people! We are not slaves! We are not going to be working for anybody.’ So the colonial Jamaican government had to support the Maroons. They had to buy their clothing, food… One of the things the Maroons did do though was to work on enforcing the citadel. That’s the fortress in Halifax. The Maroons were a fighting people. When they landed there was the fear that the French –it was in the midst of the Napoleonic Wars- the fear that the French was going to invade Nova Scotia and Canada. So they fortified the citadel. The Maroons worked on the citadel. In fact there is a gate, right now if you go the citadel in Nova Scotia; you pass through the Maroon gate. There is a gate named in honor of the Maroon for the work that they did. The Maroons were also organized in military companies as they were in Jamaica; they still kept up that tradition. They kept up also the tradition of polygamy. They kept up the Afrikan tradition of burying their dead with trade goods and so on. The refused to convert to Christianity. All in all, they were unbowed and resisted assimilation. Finally after 4 years, they got their way and they were sent to Sierra Leone, West Afrika. Not all of them, most of them left, but some of them remained here.”

Maroons of Jamaica

This important piece of history is important in understanding the spirit of the Black people in Nova Scotia today. Dr. Cooper explained:

“One of the things you know if you come to Nova Scotia and talk to people in the Black community is that everyone feels imbued with the spirit of the Maroons. People will talk about the fighting spirit of the Maroons… the spirit of resistance. People invoke that memory all the time. They are like, ‘We are like the Maroons. We don’t bow. We’re going to resist oppression.’ To this day, it is a very positive, empowering memory of the Maroons that’s here. It’s a palatable part of the culture of resistance in Nova Scotia.”

Connecting Black people from Canada to this history and connecting the Afrikan Canadian experience to the greater Afrikan Diaspora is an integral part of Afua Cooper’s work and reflects in her advice to budding historians and even poets to be committed to their work and art.

“Commitment is a hard thing because sometimes you don’t want to do the work. Sometimes it’s tiring. It bogs you down and you have the oppression coming from the wider society. Another thing equally important is to be part of a circle. You can’t do it alone. You have to be part of a community of people. Whether it’s your family, you have to find like minds. Find something that you are passionate about; that you are really interested in. If you are not interested in something it’s not going to work. Don’t be lazy. Laziness is like writing a poem and you know it needs to be revised and you know it can be better but you just kind of throw it down because it might sound good right there, but go back to it and work at it and polish it and craft it. Infuse righteousness in your work. That’s a major thing for me. I’m a Muslim. It’s what grounds me. It’s my moral compass. I mean, you can be an atheist and be a moral person. As I have said to people- I have friends who are atheist and they are some of the most moral people on the planet- morality doesn’t mean religion. I always have to check myself. I have to check my motives. Those things are important. We have to infuse our work with morality. Otherwise it just wouldn’t be anything.”

Although much too young to ponder over her legacy, Afua Cooper’s work has already left an indelible mark on the Canadian historical landscape as well as connected the Afrikan Diaspora to the Black people in Canada.

“Ever since I was 10 years old I wanted to do my work for Black people. I love Black people. I do this for the collective. I do it for myself, obviously I need to make a living and put food on the table; but what drives me is what drove Harriett Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Malcolm X and Viola Desmond and Rocky Jones and Dr. King… It’s to reach that Promised Land. As Dr. King said it’s to reach that Promised Land. We are not there yet. Not yet Uhuru. Uhuru meaning freedom. We see it every day with our kids at school. The trials and tribulation that they go through…. What the people are talking about with African Canadian young men not graduating. This is in 2014. We are not there yet. My work is for that. My work is for us to reach that Promised Land.”

Coming soon, look for more of Kentake Page’s exclusive interview with Dr. Afua Cooper as she discusses the impact of Marie Joseph Angelique on her life and Canadian history, the dynamics of the Maafa in Canada, Africville and how we can and must connect young people to history!

Dr. Afua Cooper is the James Robinson Johnston Chair in Black Canadian Studies at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia Canada. She also founded the Black Canadian Studies Association (BCSA), which she currently chairs.

To contact her, email: afua.cooper@dal.ca

Additional sources:

http://www.whoswhoinblackcanada.com/2011/04/19/dr-afua-cooper/

http://www.afuacooper.com/home_page.html