[dropcap size=small]H[/dropcap]orace King was an African American architect, engineer, and bridge builder. King built the biggest American bridges in the mid 1800’s, and is considered the most respected bridge builder of the 19th century Deep South, constructing dozens of bridges in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi. His work is still present in the amazing spiraling staircases of the Alabama State Capital.

King was born enslaved on September 8, 1807 in Chesterfield District, South Carolina. His ancestry was a mix of African, European, and Catawba. Taught to read and write at an early age, he had become a proficient carpenter and mechanic by his teenage years. Records indicate King spent his first 23 years near his birthplace, with his first introduction to bridge construction in 1824. When King’s enslaver died around 1830, he was sold to John Godwin, a contractor, who owned a successful construction business. King may have been related to the family of Godwin’s wife, Ann Wright.

In 1832, Godwin received a contract to construct a 560-foot (170 m) bridge across the Chattahoochee River from Columbus, Georgia to Girard, Alabama (today Phenix City). Initially living in Columbus, he and King moved to Girard in 1833. Although King was enslaved, Godwin treated him as a valued employee and eventually gave him considerable influence over his business. The pair began many other construction projects, including house building. They built Godwin’s house first, then King’s. This was followed by many speculative houses, resulting in nearly every early house in Girard being built by the pair. The Columbus City Bridge was the first known to be built by King, who likely planned the construction of the bridge and managed the enslaved laborers who built the span.

Between the completion of the Columbus City Bridge in 1833 and the early 1840s, King and Godwin partnered on no fewer than eight major construction projects throughout the South. By 1840, King was being publicly acknowledged as being a “co-builder” along with Godwin, an uncommon honor for an enslaved man. His prominence had eclipsed that of his enslaver and by the early 1840s, he was designing and supervising construction of major bridges at Wetumpka, Alabama and Columbus, Mississippi without Godwin’s supervision. Godwin issued five year warranties on King’s bridges because of his confidence in King’s high quality work.

While working on the Eufaula bridge, King met Tuscaloosa attorney and entrepreneur Robert Jemison, Jr., who soon began using King on a number of different projects in Lowndes County, Mississippi, including the 420-foot (130 m) Columbus, Mississippi bridge. Jemison would remain King’s friend and associate for the rest of his life. King bridged the Tallapoosa River at Tallassee, Alabama in 1845. Later that same year he built three small bridges for Jemison near Steens, Mississippi, where the latter owned several mills.

The partners also constructed some forty cotton warehouses in Apalachicola, Florida in 1834. It is thought by scholars that Godwin sent King to Oberlin College in Ohio, the first college in the United States to admit African-American students, in the mid-1830s. The two then went on to build the courthouses of Muscogee County, Georgia and Russell County, Alabama from 1839–1841, and bridges in West Point, Georgia (1838), Eufaula, Alabama (1838–39), Florence, Georgia (1840). They built a replacement for their Columbus City Bridge between Columbus and Girard in 1841, as the original had been destroyed during an 1838 flood.

In 1839, King married Frances Thomas, a free African American woman. The couple had had four boys and one girl. The King children eventually joined their father at working on various construction projects. In addition to building bridges, King constructed homes and government buildings for Godwin’s construction company. In 1841, King supervised the construction of the Russell County Courthouse in Alabama.

Despite his enslavement, King was allowed a significant income from his work and, in 1846, used some of his earnings to purchase his freedom from the Godwin family and Wright. However, under Alabama law of the time, a freed enslaved Black was only allowed to remain in the state for a year after manumission. Jemison, who served in the Alabama State Senate, arranged for the state legislature to pass a special law giving King his freedom and exempting him from the manumission law.

In 1849, the Alabama State Capitol burned, and King was hired to construct the framework of the new capitol building, as well as design and build the twin spiral entry staircases. King used his knowledge of bridge-building to cantilever the stairs’ support beams so that the staircases appeared to “float,” without any central support.

Horace King used bridge-building techniques to design the spiral staircase in the Alabama State Capitol so that a central support was not required.

Around 1855, King formed a partnership with two other men to construct a bridge, known as Moore’s Bridge, over the Chattahoochee between Newnan and Carrollton, Georgia, near Whitesburg. Instead of collecting a fee for his work, King took stock instead, gaining a one-third interest in the bridge. King moved his wife and children to the bridge about 1858, although he continued to commute between it and their other home in Alabama. Frances King and their children collected the bridge tolls and farmed at Moore’s Bridge. The earnings from Moore’s Bridge allowed King a steady income, though he continued to design and construct major bridge projects through the remainder of the 1850s, including a major bridge in Milledgeville, Georgia and a second Chattahoochee crossing in Columbus, Georgia.

As the American Civil War approached in 1860, King, like many African Americans in the South, opposed secession of the Southern states and was a confirmed Unionist. After the outbreak of hostilities, King attempted to continue his business as an architect and builder, constructing a factory and a mill in Coweta County, Georgia and a bridge in Columbus, Georgia. While working on the Columbus bridge, King was conscripted by Confederate authorities to build obstructions in the Apalachicola River, 200 miles (320 km) south of Columbus to prevent a naval attack on that city. After completing the obstructions on the Apalachicola, King was tasked to construct defenses on the Alabama River before returning to Columbus in 1863.

By this time, Columbus had become a major shipbuilding city for the Confederacy, and King and his men were assigned to assist construction of naval vessels at the Columbus Iron Works and Navy Yard. In 1863-64, King constructed a rolling mill for the Iron Works, providing cladding for Confederate ironclad warships. King’s crews also provided lumber and timbers for the Navy Yard, and was at least peripherally involved with the construction of the CSS Muscogee.

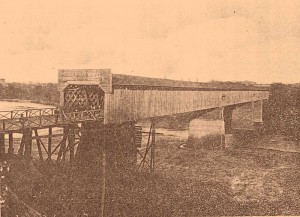

Many of King’s bridges were destroyed by Union troops. This included Moore’s Bridge, which King owned. Moore’s Bridge was destroyed by Union cavalry in July 1864. When Union soldiers assaulted Columbus in April 1865, they burnt all of King’s bridges in that city, including the one he had finished less than two years earlier.

In October 1864, his wife died leaving King a widower with five surviving children to care for. He remarried, immediately after the Civil War ended to Sarah Jane Jones McManus. Also after the war King began to prosper as he worked on the reconstruction of bridges, textile mills, cotton warehouses and public buildings destroyed during the conflict. Within six months after the war’s end, King and a partner had constructed a 32,000-square-foot (3,000 m2) cotton warehouse in Columbus and King had—for the third time—rebuilt the original Columbus City Bridge.

King’s third rebuilding of the Columbus City Bridge in 1865, six months after his previous bridge at this location was burned by Union troops. View of entrance on the Alabama side.

Over the next three years, King would construct three more bridges across the Chattahoochee in Columbus, a major bridge in West Point, Georgia, two large factories, and the Lee County, Alabama courthouse.

King was elected as a Republican to the Alabama House of Representatives, serving from 1870 to 1874. When he left the Alabama Legislature in 1872, he moved with his family to LaGrange, Georgia. While in LaGrange, King continued building bridges, but also expanded to include other construction projects, specifically businesses and schools. By the mid-1870s, King had begun to pass on his bridge construction activities to his five children, who formed the King Brothers Bridge Company. King’s health began failing in the 1880s, and he died on May 28, 1885 in LaGrange.

King received laudatory obituaries in each of Georgia’s major newspapers, a rarity for African-Americans in the 1880s South. He was posthumously inducted into the Alabama Engineers Hall of Fame at the University of Alabama. The award was accepted on his behalf by his great grandson, Horace H. King, Jr. He was remembered both for his engineering skill and for his character.

Two books have been written about Horace King: Horace King: Bridges to Freedom by Faye Gibbons and Bridging Deep South Rivers: The Life and Legend of Horace King by John S. Lupold.

Source:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horace_King_(architect)