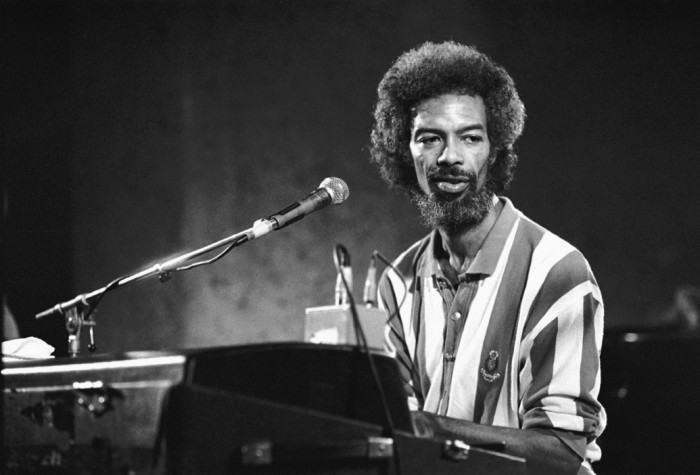

Gil Scott-Heron was the African American poet, novelist, musician, and songwriter known primarily for his work as a spoken-word performer in the 1970s and 1980s. His syncopated spoken style and critiques of politics, racism and mass media in pieces like “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” made him a notable voice of Black protest culture in the 1970s and an important early influence on hip-hop.

Scott-Heron was born in Chicago, Illinois on April 1, 1948 to parents Bobbie Scott Heron, a librarian, and Giles (Gil) Heron, a Jamaican professional soccer player. He grew up in Lincoln, Tennessee and the Bronx, New York, where he attended DeWitt Clinton High School. Heron attended Lincoln University in Pennsylvania and received an M.S. in Creative Writing from Johns Hopkins University.

In his early teens, Mr. Scott-Heron wrote detective stories, and his work as a writer won him a scholarship to the Fieldston School in the Bronx, where he was one of 5 black students in a class of 100. Following in the footsteps of Langston Hughes, he went to the historically black Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, and he wrote his first novel at 19, a murder mystery called “The Vulture.” A book of verse, “Small Talk at 125th and Lenox,” and a second novel, “The Nigger Factory,” soon followed.

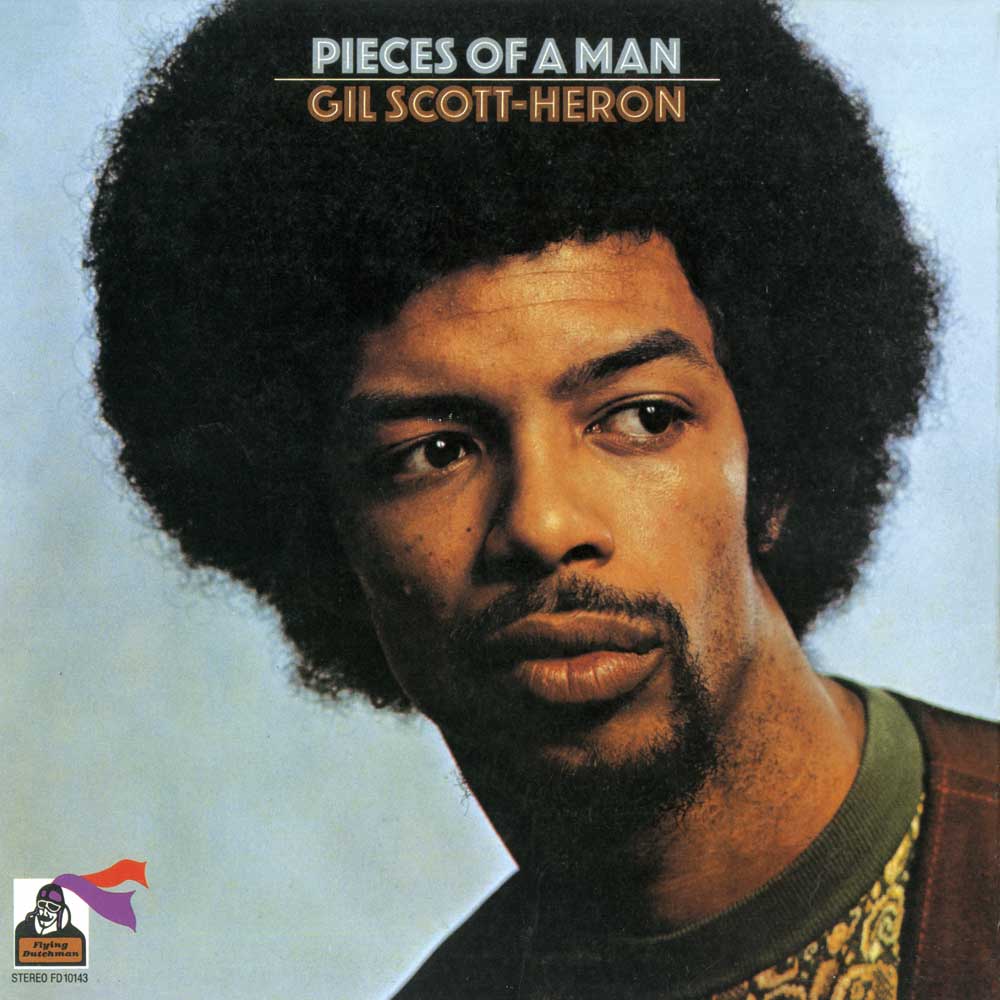

Working with a college friend, Brian Jackson, Mr. Scott-Heron turned to music in search of a wider audience. In 1970, he released his first album, New Black Poet Small Talk at 125th and Lennox, Pieces of Man (1971), Free Will (1972) and Winter in America (1974). These albums include such classic signature works as “The Revolution Will Not be Televised,” “Lady Day and John Coltrane,” “Whitey on the Moon,” “No Knock On My Brother’s Head,” and “Home Is Where the Hatred Is.” “Small Talk at 125th and Lenox,” included a live recitation of “Revolution” accompanied by conga and bongo drums. Another version of that piece, recorded with a full band including the jazz bassist Ron Carter, was released on Mr. Scott-Heron’s second album, “Pieces of a Man,” in 1971.

Clive Davis signed Scott-Heron to Arista in 1974 and began releasing his records at a frantic piece, averaging more than one a year between 1970 and 1982. In 1979 he performed alongside Bruce Springsteen, Jackson Browne and many others at the MUSE benefits at Madison Square Garden, and in 1985 he sang the protest anthem “Sun City” with Bob Dylan, Steve Van Zandt, RUN DMC, Lou Reed and Miles Davis.

Scott-Heron made a practical impact on American public life in 1980, after Stevie Wonder released Hotter Than July, on which the track Happy Birthday demanded the commemoration of the birthday of civil rights leader Martin Luther King with a national holiday. Scott-Heron went on tour with Wonder, and in Washington they campaigned to support the black congressional caucus’s proposal. Wonder and Scott-Heron fronted a petition signed by 6 million people, and in November 1983 Reagan signed the bill creating a federal holiday in January, the first falling in 1986. Scott-Heron told the US radio station NPR in 2008 that the holiday served as a “time for people to reflect on how far we have come, and how far we still have to go, in terms of being just people. Hopefully it will be a time for people to reflect on the folks that have done things to get us to where we are and where we’re going.”

He also eulogised the work of Fannie Lou Hamer, a black civil rights leader and voting activist, in his song 95 South (All of the Places We’ve Been), on the album Bridges (1977). However, though his work was often overtly political, he told the New Yorker magazine in 2010 that he sought to express more than simple sloganeering: “Your life has to consist of more than ‘black people should unite’. You hope they do, but not 24 hours a day. If you aren’t having no fun, die, because you’re running a worthless program far as I’m concerned.”

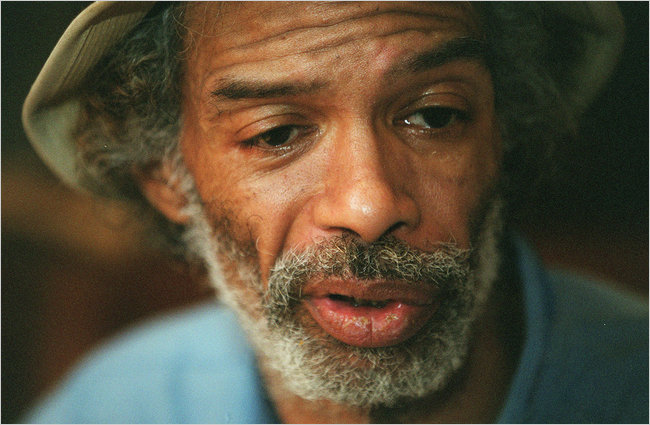

The Bottle (1974) resurfaced as an underground classic in the years following the British acid-house “summer of love” of 1988. Its incendiary rhythmic flow and compassionate lyrical exploration of the links between material poverty and the corresponding human response – a drive towards narcotic or alcoholic abandon – suited the spirit of those times perfectly and recruited a new generation of fans. Scott-Heron himself fell victim to the alcohol and substance abuse he had so long decried, and in 1985 he was dropped by Arista.

To the surprise of many, he returned to recording in 1994 with the album Spirits, on the TVT label. By then, hip-hop and rap had become the voice of young black America, and attention was again focused on his early role in the genre. In the Spirits track Message to the Messengers, Scott-Heron sent out a warning to young, nihilistic gangsta rappers and implored reflection and restraint: “Protect your community, and spread that respect around,” he urged, and rejected their use of “four-letter words” and “four-syllable words” as evidence of shallow intellects.

Meanwhile, he found fame of a more surreal, unexpected variety when he provided the voiceover for adverts for the British fizzy orange drink Tango, declaiming in stentorian tones: “You know when you’ve been Tangoed.”

He returned to the studio in 2007, and three years later released I’m New Here, produced by Richard Russell, on the British independent label XL Recordings, to wide critical acclaim. On it, he turned his lyrical contemplation inwards, commenting in confessional and haunting terms on his own loneliness, his upbringing, and repentant admissions of his own frailty: “If you gotta pay for things you done wrong, then I gotta big bill coming!”

Tracks such as Where Did the Night Go and New York Is Killing Me set his touchingly weathered baritone over minimalistic beats and production, completing the redemptive reinstatement of one of America’s most rebellious and influential voices.

In 1978 Scott-Heron married the actor Brenda Sykes, with whom he had a daughter, Gia. He also had another daughter, Che, and a son, Rumal.

Gil Scott-Heron died in a Manhattan hospital on May 27, 2011. He was 63.

Sources:

http://www.theguardian.com/music/2011/may/28/gil-scott-heron-obituary

http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/gil-scott-heron-forefather-of-hip-hop-dead-at-62-20110528#ixzz44X5NMmrK

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gil_Scott-Heron