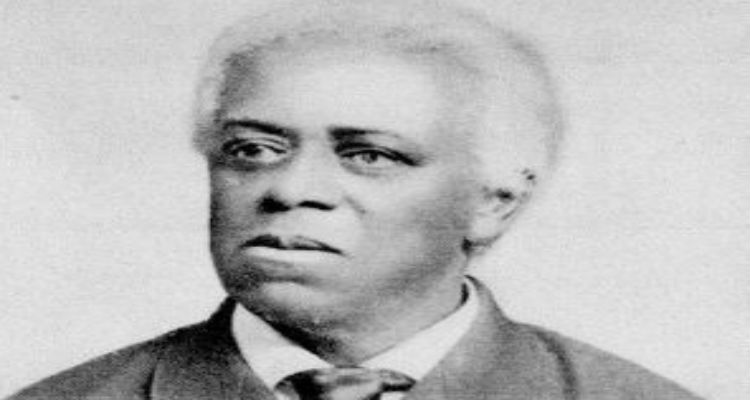

Edward Garrison Walker, the son of David Walker, came to prominence in his own right as an attorney in 1861; he was one of the first Black men to pass the Massachusetts bar. He later became a politician and in 1866, nine years after the state extended the franchise to African-American men, he and Charles Lewis Mitchell were the first two Black men elected to the Massachusetts State Legislature.

Edward Walker also known as Edwin Garrison Walker, was born free in Boston, Massachusetts to Eliza and David Walker in 1831. His exact date of birth is unknown. His mother Eliza, whose last name also is unknown, was, according to most sources, a fugitive from the Maafa (slavery). His father, David Walker, was nationally known for authoring David Walker’s Appeal, a powerful abolitionist text which was published in Boston in 1839.

Walker was educated in Boston’s public school system and while growing up trained as a leatherworker. He eventually owned his own shop and employed fifteen people. Walker, along with Lewis Hayden and Robert Morris, by now all well-known Boston abolitionists, were lauded by the New England public in 1851 for their assistance in obtaining the release of Shadrach, a fugitive.

While fighting for the release of Shadrach, Walker acquired a copy of Blackstone’s Commentaries, which piqued his interest in law. Shortly thereafter, while still a leatherworker, Walker studied law in the offices of John Q. A. Griffin and Charles A. Tweed in Georgetown, Massachusetts. After passing his law examination with ease in May, 1861, Walker became the third African American admitted to the Massachusetts Bar.

Walker soon transitioned from law into politics. Running as a Republican, in 1866 he was elected to Ward 3 of the Massachusetts General Court (the state legislature). The same day Charles L. Mitchell, also an African American, was elected to Ward 6. However, since the polls at Ward 3 closed before those at Ward 6, Walker became the second African American elected to a state legislature in the United States, following Alexander Twilight, who was elected to the Vermont Legislature in 1836, thirty years before.

While in office Walker opposed many Republican ideas and consequently the party refused to re-nominate him in 1867. Undeterred, Walker became a Democrat, leading a number of Boston African Americans to desert the GOP for the Democratic Party.

Walker forged alliances with many well known Boston politicians including Democratic General and Civil War hero Benjamin F. Butler, who was elected Governor of the state in 1883. Butler, in turn, nominated Walker as a judge. However, the Republicans in the legislature refused to ratify the nomination and instead gave the judgeship to a “loyal” African American Republican, George L. Ruffin. Walker was nominated again for three judgeships but was rejected each time by the Republican-dominated Massachusetts legislature.

Partly in response to his difficulties as a rare black Democrat, Walker and other black leaders including George T. Downing of Rhode Island, initiated in 1885 the Negro Political Independence Movement. Five years later, in 1890, Walker was elected president of the Colored National League. In 1896 he received the nomination for the U.S. Presidency by the Negro Party, a short-lived third party movement.

Edward Garrison Walker died on January 13, 1901 in Boston, Massachusetts. He was nearly 70 years old.

Source:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_G._Walker