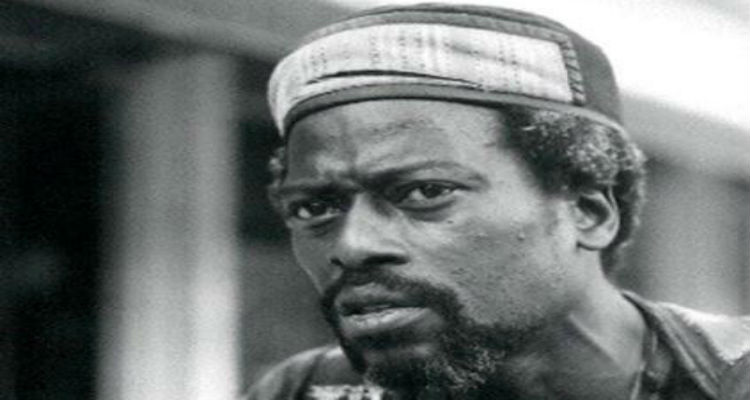

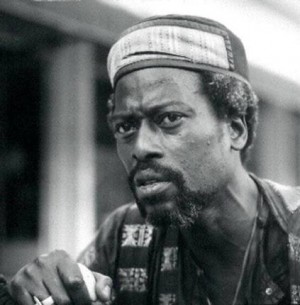

Djibril Diop Mambéty (January 1945 – July 23, 1998) was a Senegalese film director, actor, composer, and poet, loved and admired by critics and audiences all over the world. Though he made only a small number of films, they received international acclaim for their original and experimental cinematic technique and non-linear, unconventional narrative style.

Djibril Diop Mambéty (January 1945 – July 23, 1998) was a Senegalese film director, actor, composer, and poet, loved and admired by critics and audiences all over the world. Though he made only a small number of films, they received international acclaim for their original and experimental cinematic technique and non-linear, unconventional narrative style.

The son of a Muslim cleric and member of the Lebou nation, Djibril Diop Mambéty was born near Senegal’s capital city of Dakar in Colobane, a town featured prominently in some of his films. Mambéty’s interest in cinema began with theater. He studied drama in Senegal, and worked as a stage actor at the Daniel Sorano National Theater in Dakar until he was expelled for disciplinary reasons.

In 1969, at age 24, without any formal training in filmmaking, Mambéty directed and produced his first short film, Contras’ City (A City of Contrasts). Mambety’s next short film, Badou Boy, was released the following year. Badou Boy, won the Silver Tanit award at the 1970 Carthage Film Festival in Tunisia.

In 1973, Mambety released his masterpiece, the technically sophisticated and richly symbolic first feature-length film, Touki Bouki (The hyena’s journey), which received the International Critics Award at Cannes Film Festival and won the Special Jury Award at the Moscow Film Festival, bringing the Senegalese director international attention and acclaim. It was unlike anything in the history of African cinema; today, film scholars around the world agree that Touki Bouki is a classic. Its central themes are wealth, youth, and delusion: Mory and Anta are a fashionable young Senegalese couple on the run–from their families, their home, and their future–dreaming of Europe. The story revolves around the couple’s brash and illegal attempts to get enough cash for boat tickets to Paris. But it is less the narrative than its mode of presentation that carries the burden of meaning. Mambety mixes elements of several storytelling techniques to create phantasmal images of postcolonial African society’s myriad failings. His presentation invites the viewer to understand these images in dialectical terms.

Despite the film’s success, twenty years passed before Mambéty made another feature film. During this hiatus he made one short film in 1989, Parlons Grandmère (Let’s talk Grandmother), while helping his friend, the Burkinabe director Idrissa Ouedraogo, with the filming of Yaaba.

In 1992, Mambety returned to the limelight with an ambitious new film. Hyènes (Hyenas), Mambéty’s second and final feature film, was an adaptation of Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s play The Visit and was conceptualized as a continuation of Touki Bouki. The grand theme, once again, is human greed. As Mambety himself observed, the story shows how neocolonial relations in Africa are “betraying the hopes of independence for the false promises of Western materialism,” and how Africans have been corrupted by that materialism. We follow Linguère Ramatou, a wealthy woman who returns from abroad to the desolate village of Colobane, her birthplace. Many years before, she had been seduced by a young man, impregnated, and abandoned for a wealthier wife; she was then mercilessly ostracized by her neighbors. Now “as rich as the World Bank,” Linguère offers lavish gifts and huge sums of money to the villagers–in exchange for the death of her onetime lover. They accept the deal, and Mambety makes it easy for us to see why. The Colobane of Hyènes is a sad reminder of the economic disintegration, corruption, and consumer culture that has enveloped Africa since the 1960s. “We have sold our souls too cheaply,” Mambety once said. “We are done for if we have traded our souls for money. That is why childhood is my last refuge.” But what remains of Colobane is not the magical childhood Mambety pines for. In the last shot of Hyènes, a bulldozer erases the village from the face of the earth. A Senegalese viewer, one writer has claimed, “would know what rose in its place: the real-life Colobane, a notorious thieves’ market on the edge of Dakar.”

Hyènes confirmed Mambety’s stature as one of Africa’s greatest auteurs, and it seemed to herald the beginning of a new and productive phase in his career. Mambety began a trilogy of short films called Contes des Petites Gens (Tales of the Little People), whom he called “the only true, consistent, unaffected people in the world, for whom every morning brings the same question: how to preserve what is essential to themselves.”

The first of the three films was Le Franc (1994), a comedy about a poor musician who wins the lottery, exposes the havoc wrought upon the people of Senegal by France’s devaluation of the West African Franc (CFA). Mambety was editing the second film in the trilogy, La petite vendeuse de Soleil (The Little Girl Who Sold The Sun), when he died, which premiered posthumously in 1999. His early death to lung cancer, at age 53, occurred in a Paris hospital.

Filmography

Contras’city (1968)

Badou Boy (1970)

Touki Bouki/The Journey of the Hyena (1973), International Critic’s Prize at Cannes and Special Jury Prize Moscow Film Festival[6]

Parlons Grand-mère (Let’s talk Grandmother) (1989)

Hyènes (1992)

Le Franc (1994)

La Petite Vendeuse de Soleil (1999)

Contras’city

Djibril Diop Mambéty’s earliest film, a short entitled Contras’city (1968), highlighted the contrasts of cosmopolitanism and unrestrained ostentation in Dakar’s baroque architecture against the modest, everyday lives of the Senegalese. Mambéty’s recurrent theme of hybridity—the blending of elements from precolonial Africa and the colonial West in a neocolonial African context—is already evident in Contras’city, which is considered Africa’s first comedy film.

Badou Boy

In 1970 Mambéty released his next short, Badou Boy, another sarcastic look at Senegal’s capital that followed the adventures of what the director described as a “somewhat immoral street urchin who is very much like myself”.[7] The contest pits the non-conformist individual against an absurdly caricatured policeman who pursues the protagonist through comedically improbable scenarios. Badou Boy celebrates an urban subculture while parodying the state.

Touki Bouki

Considered by many to be his most daring and important film, Mambéty’s feature-length debut, Touki Bouki (The Hyena’s Journey) more fully developed his earlier themes of hybridity and individual marginality and isolation. Based on his own story and script, Djibril Diop Mambéty made Touki Bouki with a budget of $30,000—obtained in part from the Senegalese government. Though influenced by French New Wave, Touki Bouki displays a style all its own. Its camerawork and soundtrack have a frenetic rhythm uncharacteristic of most African films—known for their often deliberately slow-paced, linearly evolving narratives. Through jump cuts, colliding montage, dissonant sonic accompaniment, and the juxtaposition of premodern, pastoral and modern sounds and visual elements, Touki Bouki conveys and grapples with the hybridization of Senegal. A pair of lovers, Mory and Anta, fantasize about fleeing Dakar for a mythic and romanticized France. The film follows them as they try to scavenge and hustle the funds for their escape. They both make it to the steamliner that would transport them to Paris, but before it disembarks, Mory is drawn back to Dakar and cannot succumb to the seduction of the West. Touki Bouki won the Special Jury Award at the Moscow film Festival and the International Critics Award at Cannes.

Touki Bouki ranked #52 in Empire magazines “The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema” in 2010.

Hyènes

An African adaptation of Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s famous Swiss play, The Visit, Hyènes (Hyenas) tells the story of Linguere Ramatou, an aging, wealthy woman who revisits her home village—and Mambéty’s—of Colobane. Linguere offers a disturbing proposition to the people of Colobane and lavishes luxuries upon them to persuade them. This embittered woman, “as rich as the World Bank,” will bestow upon Colobane a fortune in exchange for the murder of Dramaan Drameh, a local shopkeeper who abandoned her after a love affair and her illegitimate pregnancy when she was 16. The intimate story of love and revenge between Linguere and Dramaan parallels a critique of neocolonialism and African consumerism. Mambéty once said, “We have sold our souls too cheaply. We are done for if we have traded our souls for money”[3] Although its characters are distinct, Mambéty considered Hyènes to be a continuation of Touki Bouki and a further exploration of its themes of power and insanity. Wasis Diop, younger brother of Djibril Diop Mambéty, is responsible for the film’s soundtrack.

The film is distributed by California Newsreel Productions.

Le Franc

This first film in Mambéty’s uncompleted trilogy, Contes des Petites Gens (Tales of Little People), Le Franc (1994) uses the French government’s devaluation of the CFA Franc to comment on the absurd schemes people concoct to survive a system that rewards greed rather than merit. The film features a poor musician, Marigo, who finds solace in playing his congoma, which has been confiscated because of his debt. Marigo plays the lottery, and despite winning, encounters obstacles to claiming the reward. The film is both slapstick and symbolic of the lottery-style luck that benefits some and hampers others in the global economy.

Le Franc is part of the project, Three Tales from Senegal which also includes “Picc Mi” (Little Bird) and “Fary l’anesse” (Fary the Donkey).

The film is distributed by California Newsreel Productions.

La Petite Vendeuse de Soleil

As the second installment in Mambéty’s trilogy exalting the lives and promise found among ordinary Senegalese, the 45-minute film, La Petite Vendeuse de Soleil (The Little Girl Who Sold the Sun) depicts a young beggar girl, Sili, who on crutches, confidently makes her way through a city of obstacles, evading a group of bullies, and selling newspapers to make money for herself and her blind grandmother. Mambéty dedicates his last film to “the courage of street children”. His luminous main character, Sili, manages to make this a sympathetic and optimistic look at the struggle and potential of Africa’s most oppressed—young, female, poor, disabled. The movie is accompanied by a score by Mambéty’s brother, Wasis Diop. This film was selected as one of the ten best films of 2000 by the Village Voice. Reviewer for The New York Times, A.O. Scott described the film as a “masterpiece of understated humanity.”

Source:

http://newsreel.org/articles/mambety.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Djibril_Diop_Mamb%C3%A9ty