“First man to die for the flag we now hold high was a Black man” (a line from Stevie Wonder’s song “Black Man”).

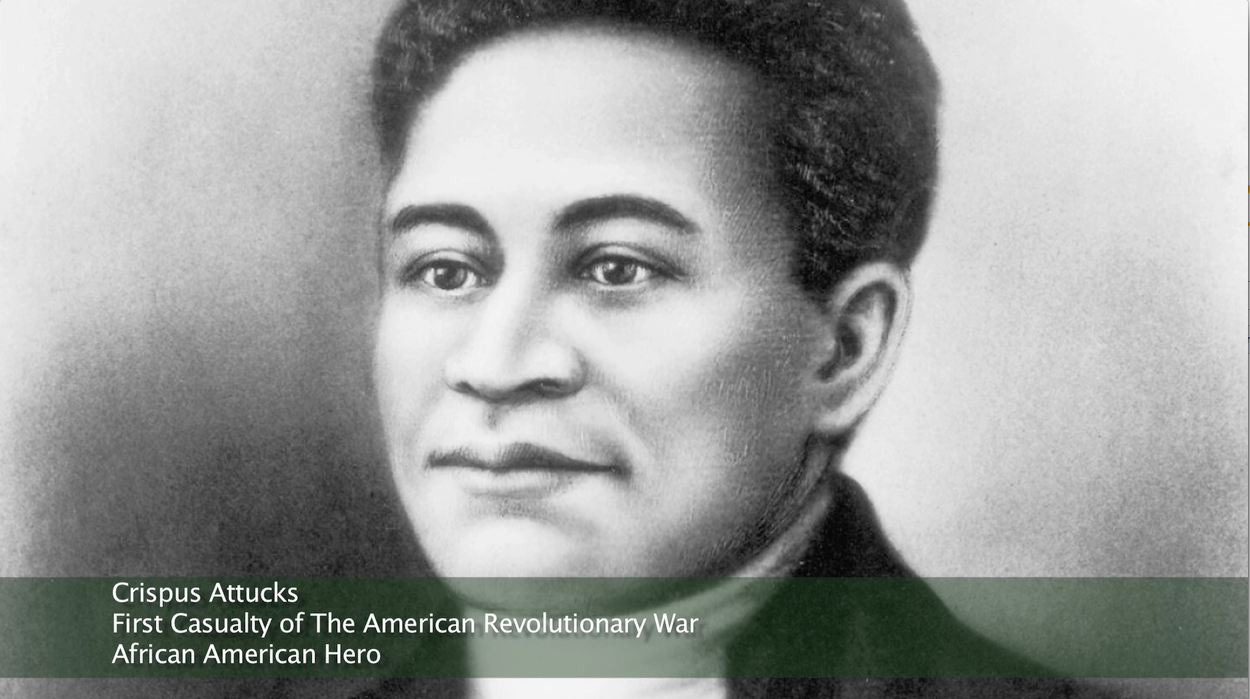

Crispus Attucks is widely considered the first casualty of the Boston Massacre, in Massachusetts, and the first American casualty in the American Revolutionary War. Aside from the event of his death, little is known for certain about his life. Despite the lack of clarity, Attucks became an icon of the anti-slavery movement in the 18th century. He was held up as the first martyr of the American Revolution, along with the others killed. In the early 19th century, as the abolitionist movement gained momentum in Boston, supporters lauded Attucks as an African American who played a heroic role in the history of the United States.

Historians disagree on whether Crispus Attucks was a free man or a fugitive, but agree that he was of Wampanoag and African descent. Two major sources of eyewitness testimony about the Boston Massacre, both published in 1770, did not refer to Attucks as “Black”; it appeared that Bostonians of European descent viewed him as being of mixed ethnicity. According to a contemporary account in the Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia), Attucks was reported as being a “[Mixed-race] man, named Crispus Attucks, who was born in Framingham, but lately belonged to New-Providence, and was here in order to go for North Carolina…”

Attucks is believed to have been born around 1723, in Framingham, Massachusetts. Born into slavery, Attucks was the son of Prince Yonger, an enslaved man shipped to America from Africa, and Nancy Attucks, a Natick Indian. Attucks was also descended from John Attucks of Massachusetts, who was hanged during King Philip’s War.

Attucks’s status at the time of the massacre has been a matter of debate for historians. However, his descendants maintain he was enslaved and had self-emancipated himself sometime in his late 20s.

In 1750 William Brown, an enslaver in Framingham, advertised for the return of a runaway named Crispus in the Boston Gazette in which he offered to pay £10 for the return of a young runaway.

“Ran away from his Master William Brown from Framingham, on the 30th of Sept. last,” the advertisement read. “A Molatto Fellow, about 27 Years of age, named Crispas, 6 Feet two Inches high, short curl’d Hair, his Knees nearer together than common: had on a light colour’d Bearskin Coat.”

What is known about Attucks is that he became a sailor and spent over two decades at sea often working on whalers, which involved long voyages. Many historians also believe that he went by the alias Michael Johnson in order to avoid being caught. He may only have been temporarily in Boston in early 1770, having recently returned from a voyage to the Bahamas. He was due to leave shortly afterwards on a ship for North Carolina.

In 1768, British troops were dispatched to Boston and were repulsed by both African and European patriots. Tensions had been escalating between the two sides, as British control over the colonies tightened. Attucks was one of those directly affected by the worsening situation. As a seaman he constantly lived with the threat he could be forced into the British navy, while back on land, British soldiers regularly took part-time work away from colonists. The struggle between the two sides reached a peak in 1770.

On March 5th, a crowd – composed mainly of “saucy boys, [Blacks] and mulattoes, Irish… and outlandish Jack Tars” – gathered and traded insults with the British soldiers. In the center of this crowd stood an imposing man. His name was Crispus Attucks, and he was a Massachusetts native who had escaped the Maafa (slavery) and sailed the seas. Tall, brawny, with a look that “was enough to terrify any person,” Attucks was well known around the docks in lower Boston.

When he spoke, men listened. Where he commanded, men acted. When the people faltered, it was Attucks, who rallied the crow and urged them to stand their ground. The people responding to his leadership stood firm; so did the British soldiers. The two sides exchanged insults and a fight flared.

Attucks who seemed to have been everywhere that night, led a group of citizens who drove the soldiers back to the gates of the barracks. The soldiers rallied and drove the Boston crowd back. In the midst of all this two things happened that ignited the crowd: someone rang a fire bell, filling the streets with frightened and excited people; and a barber’s apprentice ran through the crowd holding his head and screaming, “Murder! Murder!”

The crowd split into three with the largest group following Crispus Attucks up King Street and gathered before the sentry in the square. The barber’s apprentice came up and said, “This is the soldier who knocked me down.”

Someone said, “Kill him! Knock his head off!”

“Don’t be afraid,” Attucks and his group cried. “They dare not fire.”

A stick sailed over their head and hit the soldier who fell back, lifted his musket and fired. The bullet hit Attucks, who pitched forward in the gutter. Two others were killed instantly and two others later died from wounds.

As Attucks fell so did the British empire, and from his last breath rose the foundation of American independence. Attucks became a martyr, with his death also adding energy to the talk against the Maafa (slavery).

Attucks’s body was transported to Faneuil Hall, where he and the others killed in the attack lay in state. City leaders even waived the laws around Black burials and permitted Attucks to be buried with the others at the Park Street cemetery.

In the years since his death, Attucks’s legacy has continued to endure, first with the American colonists eager to break from British rule, and later among 19th century abolitionists and 20th century civil rights activists:

1858, Boston-area abolitionists, including William Cooper Nell, established “Crispus Attucks Day” to commemorate him.

1886, the places where Crispus Attucks and Samuel Gray fell were marked by circles on the pavement. Within each circle, a hub with spokes leads out to form a wheel.

1888, a monument honoring Attucks and the other victims of the Boston Massacre was erected on Boston Common. It is over 25 feet high and about 10 feet wide. The “bas-relief” (raised portion on the face of the main part of the monument) portrays the Boston Massacre, with Attucks lying in the foreground. Under the scene is the date, March 5, 1770. Above the bas-relief stands a female figure, Free America, holding the broken chain of oppression in her right hand. Beneath her right foot, she crushes the royal crown of England. At the left of the figure, is an eagle. Thirteen stars are cut into one of the faces of the monument. Beneath these stars in raised letters are the names of the five men who were killed that day: Crispus Attucks, Samuel Gray, James Caldwell, Samuel Maverick, and Patrick Carr. Some men died a day later.

*Photo Credit: Crispus Attucks via http://mgjansen.com/crispus-attucks-high-school/

Source:

“From Slavery to Freedom by John Hope Franklin

“Before The Mayflower” by Lerone Bennett, Jr.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crispus_Attucks