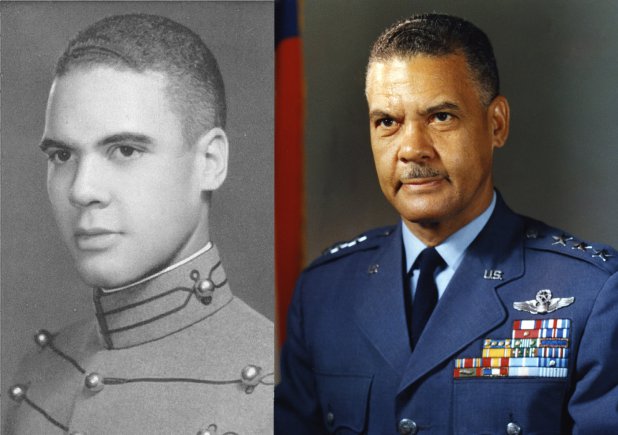

Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., born December 18, 1912 in Washington, D.C., was a pilot, officer, and administrator who became the first African American general in the U.S. Air Force. His father, Benjamin O. Davis, Sr., was the first African American to become a general in any branch of the U.S. military.

Davis studied at the University of Chicago before entering the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, in 1932. After graduating in 1936 he was commissioned in the infantry and in 1941 was among the first group of African Americans admitted to the Army Air Corps and to pilot training. Upon his graduation he was swiftly promoted to lieutenant colonel, and he organized the 99th Pursuit Squadron, the first entirely African American air unit, which flew tactical support missions in the Mediterranean theatre.

His first posting was with the all-black 24th Infantry Regiment at Fort Benning, GA. He was not allowed into the base officers’ club, a snub he would regard as one of the most insulting actions taken against him in 37 years of military life. He was later assigned to teach military tactics at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, something his father had done years before. It was the Army’s way to avoid having a Black command whyte soldiers.

In 1943 he organized and commanded the 332nd Fighter Group (the Tuskegee Airmen). By the end of the war Davis himself had flown 60 combat missions and had been promoted to colonel. The airmen commanded by Davis compiled an outstanding record in combat against the German Luftwaffe in the European theater during World War II. They shot down 111 planes and destroyed or damaged 273 on the ground at a cost of more than 70 pilots killed in action or missing. They never lost a U.S. bomber to enemy fighters on their escort missions. As the leader of numerous missions, Davis received the Silver Star for a strafing run into Austria and the Distinguished Flying Cross for a bomber-escort mission to Munich. In July 1948, President Harry Truman signed an executive order providing for integration of the armed forces. Davis helped draft an Air Force blueprint on integration that went into effect the following year.

In the summer of 1949, Davis attended the Air War College, a key assignment because promotion beyond colonel depended upon attending War College. Before Davis did so, no black officer in any service had ever attended War College—segregation had barred such attendance.

Davis excelled, despite the fact that the Air War College was located on a base in Montgomery, Alabama, an area hostile to any African Americans who aspired to rise economically or professionally. The best restaurants, hotels, and housing in the city were closed to Davis and his wife, Aggie. He and Mrs. Davis could anger the bigots among Montgomery’s whytes just by driving a late-model automobile. Davis detested this treatment but tolerated it to graduate from the Air War College. Like many of the best in his class of 1950, Davis moved from the Air War College to the Pentagon, where he served at Headquarters USAF.

Soon after arriving in Washington, Davis was made chief of the Air Defense Branch of Air Force operations, a prestigious position in which he supervised white officers and enlisted men. So successful was Davis in his Pentagon position that in 1953, while the Korean War was still raging, the Air Force assigned him to take command of the 51st Fighter-Interceptor Wing, Suwon AB, South Korea.

Davis thrived in this assignment, supervising a wing of thousands of airmen, almost all white. The Air Force learned that white airmen and officers would work loyally for a black commander, and the wing was as effective as any other Air Force unit in Asia. Having again demonstrated his skills as a commander, Davis was transferred to Japan, where he was appointed director of operations and training in Far East Air Forces. Three months later, he was promoted to brigadier general, the first black officer in the Air Force to achieve that grade.

Davis was soon reassigned to what proved to be his most significant postwar position—vice commander of 13th Air Force and commander of Air Task Force 13 (Provisional) at Taipei, Taiwan. He was to build a defensive air force from scratch, to deter Communist forces on mainland China from launching an air or sea attack on the Republic of China on Taiwan. In two years Davis built a formidable defensive air force.

In 1959 Davis became the first African American officer to reach the rank of major general (a two-star general) in the air force and was promoted to lieutenant general (a three-star general) in 1965.

Davis next moved to 12th Air Force in Germany and later became the deputy chief of staff for operations for US Air Forces in Europe. He returned to the US in 1961 as USAF director of manpower and organization. He served in the Pentagon for four years, earning a third star, and moved in April 1965 to Korea to become chief of staff of the United Nations Command and US Forces Korea.

Davis succeeded in Korea and became commander of 13th Air Force in August 1967, taking command of more than 55,000 people all over Asia, including many thousands who were flying and fighting in the Vietnam War. Davis was responsible for the air defense of the Philippines as well. He held this post for a year.

Davis then moved back to the US, where he was assigned as deputy commander in chief of US Strike Command. No other assignment for Davis had such worldwide implications as this assignment, and he traveled widely to see for himself the conditions under which his men and women might have to fight.

After two years as the deputy commander in chief, in 1970, he retired from the Air Force. He had served more than 33 years on active duty and had been all around the world. He had excelled in every position, and he left the Air Force and the military service a much better institution than he had found it. At the time of Davis’s retirement, he held the rank of lieutenant general, but on December 9, 1998, President Bill Clinton awarded him a fourth star, raising him to the rank of full general.

Davis was no longer in the Air Force, but his professional life was far from over. He became the director of public safety for Cleveland, Ohio, overseeing the city’s fire and police departments. Later, Davis became director of civil aviation security and an assistant secretary at the US Department of Transportation.

After retiring from the Department of Transportation in 1975, he followed in his father’s footsteps again by serving on the American Battle Monuments Commission. Finally, in 1991 Davis wrote his memoirs, relating his challenges and achievements over the years in his book Benjamin O. Davis, Jr.: American.

General Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. passed away on July 4, 2002 and was buried with full military honors on July 17, 2002 at Arlington National Cemetery (his wife Agatha had died earlier in the year). In addition to the honor of being buried at Arlington National Cemetery, Davis received many accolades over the years included having a number of schools named after him. His military decorations include:

Air Force Distinguished Service Medal

Army Distinguished Service Medal

Air Medal with four oak leaf clusters

Philippine Legion of Honor

Legion of Merit with two oak leaf clusters

Air Force Commendation Medal with two oak leaf clusters

Silver Star

Distinguished Flying Cross

Sources:

http://www.britannica.com/biography/Benjamin-O-Davis-Jr

http://www.aaregistry.org/historic_events/view/military-pioneer-benjamin-o-davis-jr

http://www.aviation-history.com/airmen/davis.htm

http://www.greatblackheroes.com/government/benjamin-o-davis-jr/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benjamin_O._Davis,_Jr.