“Africa will furnish a development of civilization which the world has never yet witnessed. Its great peculiarity will be its mortal element.”

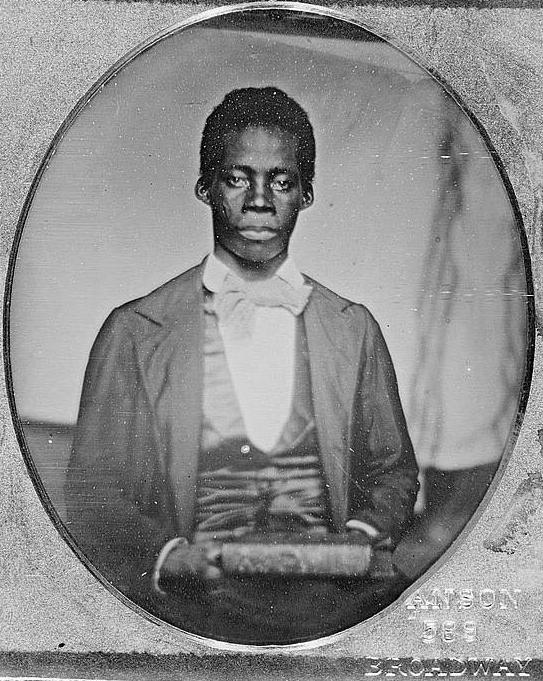

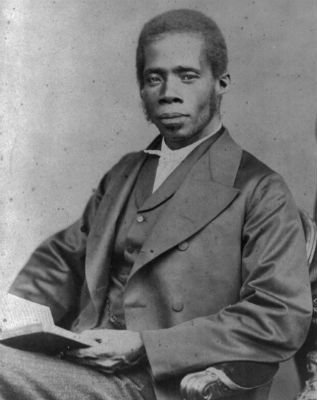

Edward Wilmot Blyden was a Liberian educator, writer, diplomat, and statesman. During the late 19th century, Blyden was the best known and highly respected African intellectual in the Western world. It was Blyden, who first coined the phrase, “Africa for the Africans,” and because of this, he is known as the “Father of Pan-African Ideals”.

Edward Blyden was born in St. Thomas, Virgin Islands, on Aug. 3, 1832, of free, literate parents of Ibo descent. Blyden was recognized in his youth for his talents and drive. He was educated and mentored by John Knox, an American Protestant minister, who encouraged him to continue his education in the United States. Blyden went to the United States in May 1850 for theological studies but was refused admission to three Northern theological seminaries because of racism. In January 1851 he emigrated to Liberia, an African American colony which had become independent as a republic in 1847.

Blyden continued his formal education at Alexander High School, in Monrovia, and was appointed the principal in 1858. From 1855 to 1856, he edited the Liberia Herald and wrote the column “A Voice From Bleeding Africa”. In 1862 he was appointed professor of classics at the newly opened Liberia College, a position he held until 1871. Although Blyden was self-taught beyond high school, he became an able and versatile linguist, classicist, theologian, historian, and sociologist. From 1864 to 1866, in addition to his professorial duties, Blyden acted as secretary of state of Liberia.

From 1871 to 1873 Blyden lived in Freetown, Sierra Leone. There he edited Negro, the first explicitly pan-African journal in West Africa. Between 1874 and 1885 Blyden was again based in Liberia, holding various high academic and governmental offices. In 1885 he was an unsuccessful candidate for the Liberian presidency.

After 1885 Blyden divided his time between Liberia, Sierra Leone and Lagos.

In Freetown, Blyden helped to edit the Sierra Leone News, which he had assisted in founding in 1884 “to serve the interest of West Africa … and the race generally.” He also had helped found and edit the Freetown West African Reporter (1874-1882), whose declared aim was to forge a bond of unity among English-speaking West Africans. From 1901 to 1906, Blyden directed the education of Muslims at an institution in Sierra Leone, when he lived in Freetown. He became passionate about Islam during this period, recommending it to African Americans as the major religion most in keeping with their historic roots in Africa. He also led two important expeditions to Fouta Djallon in the interior.

Blyden served Liberia again in the capacities of ambassador to Britain and France. As a diplomat, Blyden traveled to the United States, where he spoke to major Black churches about his work in Africa. Blyden believed that African-Americans could end their suffering of racial discrimination by returning to Africa and helping to develop it. He was criticized by African-Americans who wanted to gain full civil rights in their birth nation of the United States and did not identify with Africa.

In 1891 and 1894 he spent several months in Lagos and worked there in 1896-1897 as a government agent for native affairs. While in Lagos he wrote regularly for the Lagos Weekly Record, one of the earliest propagators of Nigerian and West African nationalism.

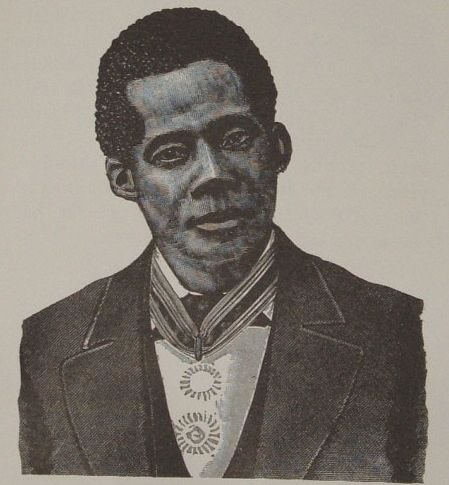

Although Blyden held many important positions, it is more as a man of ideas than as a man of action that he is historically significant. He saw himself as a champion and defender of his race and in this role produced more than two dozen pamphlets and books, the most important of which are A Voice from Bleeding Africa (1856); Liberia’s Offering (1862); The Negro in Ancient History (1869); The West African University (1872); From West Africa to Palestine (1873); Christianity, Islam and the Negro Race (1887), his major work; The Jewish Question (1898); West Africa before Europe (1905); and Africa Life and Customs (1908). Unlike his peers in the West, Blyden articulated a vision of African development that profoundly disagreed with conventional views.

Blyden, who was a nominal Christian, argued that a legion of Christianized and Western-educated [Blacks] would not lead Africa to the promised land of modernity and continental development. He argued that Christianity has had a demoralizing effect on Blacks whereas Islam, on the other hand, has had a unifying and elevating impact. He also believed that education was being used as one of the critical instruments to support and continue the colonization and exploitation of Africa. According to him, “All educated [Blacks] suffer from a kind of slavery in many ways far more subversive of the real welfare of the race than the ancient physical fetters. The slavery of the mind is far more destructive than that of the body.”

As an educator and college president, Blyden waged a battle for what he called the “Decolonization of the African mind.” In his 1881 Inaugural Address as the newly installed president of Liberia College, he talked about his vision of independent African colleges producing a new generation of African youth. He declared, “It is our hope and expectation that there will rise up men, aided by institution and culture, …imbued with public spirit, who will know how to live and work and prosper…how to use all favoring outward conditions, how to triumph by intelligence, by tact, by industry, by perseverance, over the indifference of their own people, and how to overcome the scorn and opposition of the enemies of the race…” Blyden argued that education “…should aim…not simply [for the provision of] information, but [for] the formation of the mind. The formation of the mind being secured, the information will take care of itself. Mere information of itself is not power – but the ability to know how to use that information – and this ability belongs to the mind that is disciplined, trained, [and] formed. It may be a pleasant pastime to store the mind with facts…but if the mind is not trained to apply them, they will lie there like so much useless lumber.”

Through the proper educational curriculum and sensitivity to the value of native African culture, Blyden believed that a generation of African leaders and scholars could be groomed to defeat colonialism and embrace modernity that could be blended with native cultural resources. He maintained that the core of Africa’s educational curriculum should be based upon traditional concepts of education. At its core, this curriculum must acknowledge that “the African view of the universe is based upon the truth that man, nature, the universe, and God are in harmony. There is no alienation. The basic model[s] of human action [are] cooperation, peace, and building great projects. Th[ese are] diametrically opposed by the European worldview which sees man as alienated from God, at war with nature, and surrounded by an indifferent universe.”

Blyden was a pioneer in the struggle to liberate and decolonize the African mind and to establish an independent African educational institution. At the turn of the century, he stood alone with his articulate defense of traditional African cultural institutions and their compatibility with modernity. In 1893 Blyden issued this challenge to the African world:

It is sad to think that there are some Africans, especially among those who have enjoyed the advantages of foreign training, who are blind enough to the radical facts of humanity as to say, ‘Let us do away with our African personality and be lost, if possible, in another race’. Preach this doctrine as much as you like, no one will do it, for no one can do it, for when you have done away with your personality, you have done away with yourselves. Your place has been assigned you in the universe as Africans, and there is no room for you as anything else.

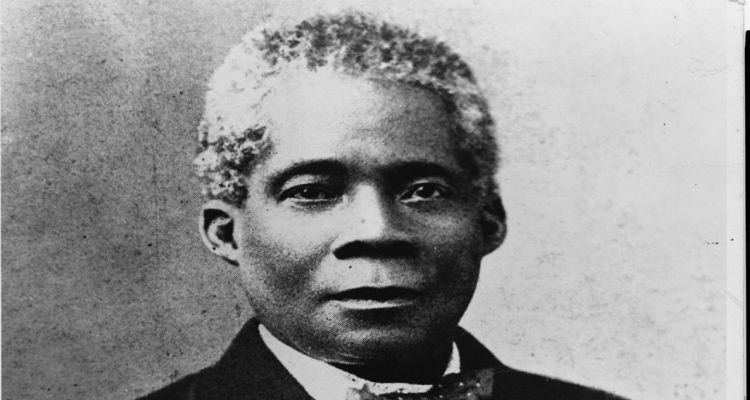

Blyden died on February 7, 1912.

Personal Life

Blyden married Sarah Yates, an Americo-Liberian from the prominent Yates family. She was the daughter of Hilary Yates and niece of Beverly Page Yates, who served as vice-president of Liberia from 1856 to 1860 under President Stephen Allen Benson. She and Blyden had three children together.

Later while living in Freetown, Sierra Leone, Blyden had a long-term relationship with Anna Erskine, an African-American woman from Louisiana. She was a granddaughter of James Spriggs-Payne, who was twice elected as the President of Liberia. Erskine and Blyden had five children together, and his direct descendants living in Sierra Leone are from this union. They have been considered part of the Krio population. Some Blyden descendants continue to live in Freetown, among them Sylvia Blyden, publisher of the Awareness Times.

Legacy

Edward Wilmot Blyden has left an indelible mark on the pages of history. Blyden was not only one of the most original thinkers of his time; he was undisputedly the foremost African intellectual of the 19th century. His brilliant career, in both Liberia and Sierra Leone spanned the fields of religion, education, journalism, politics, and philosophy. He is best remembered as an African patriot whose writings contributed to the rise of Pan-Africanism and West African nationalism.

Blyden’s idea’s and speeches urging a return to Africa and the re-creation of an African Nation were to seed African consciousness movements all over the world. There is an unbroken line of black leaders that inherited his ideas, directly or indirectly. W.E.B. DuBois and Marcus Garvey exploded them into the twentieth century, continuing to champion the theme of a return to Africa. Their political ideas, in turn, became a source for the leaders of African independence movements of the fifties and sixties- Nkrumah, Nyerere, Sekou Toure and Blyden’s own grandson, Edward W. Blyden III whose Sierra Leone Independence Movement (SLIM) played a key role in winning Sierra Leone’s independence from Great Britain. In South Africa, President Thabo Mbeki generously sprinkles his speeches with mention of, and quotes from Blyden, and in Ethiopia his written work is closely studied by Rastafarians.

“There is a talent entrusted to you. It is your duty to call into action the highest forms of your being. It does not matter what your calling may be – whether it be what men call menial or what the world calls honorable – whether it be to speak in the halls of Congress or to sweep out those halls – whether it be to wait upon others or to be waited on— it is the manner of using your faculties that will determine the result- that will determine your true influence in this world and your status in the world to come. Everyone should do his part to advance humanity. Each should exert himself to be a helper in progress. Whatever your condition, you do occupy some room in the world; what are you doing to make a return for the room you occupy? There are so many of our people who fail to realize their responsibility, who fail to hear the inspiring call of the past and the prophetic call of the future.”

Source:

http://africaunbound.org/index.php/aumagazine/issue-1/item/edward-blyden-on-the-struggle-for-african-liberation-2.html

http://biography.yourdictionary.com/edward-wilmot-blyden

http://www.columbia.edu/~hcb8/EWB_Museum/Legacy.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Wilmot_Blyden

1 comment

A great man that had influence on African history. May your soul rest in peace, Blyden.