On July 13, 1863, anti-draft violence erupted in New York City, resulting in four days of bloodshed, arson, looting, and mayhem. The New York City Draft Riot, with an official death toll of 119, remains the bloodiest outbreak of civil disorder in American history.

The Union Conscription Act of Mar. 3, 1863, provided that all able-bodied males between the ages of 20 and 45 were liable to military service, however a drafted man who furnished an acceptable substitute or paid the government $300 was excused. Between July 13 and 16, 1863, the city’s poor working-class men, primarily ethnic Irish, bloodily protested the federally-imposed draft. Initially intended to express anger at the draft, and those whose wealth allowed them to purchase substitutes for military service, the protests turned into a race riot. Abolitionists and African-Americans were especially singled out for attack. Many African-Americans were beaten to death, and an orphanage was burned, leaving hundreds of African-American children homeless. The official death toll was listed at 119. Eleven African-American men were brutally murdered during the riot. The demographics of the city changed as a result of the riot. So many African-Americans left Manhattan permanently (many moving to Brooklyn), that by 1865 their population fell below 10,000, the number in 1820.

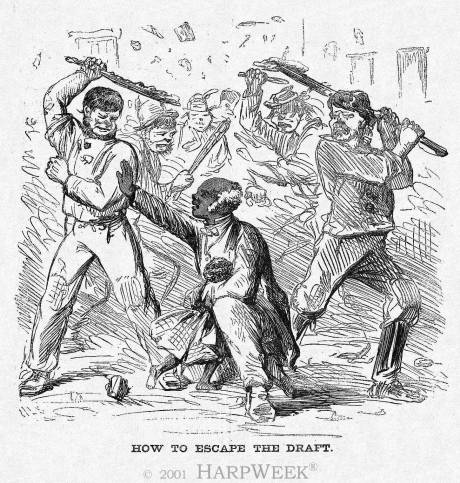

In this cartoon, a gang of Irish-American rioters prepares to assault an elderly Black man who shields a Black child in his arm.

At 6 a.m. on Monday, July 13, hundreds of the city’s European working-class men marched in protest against the draft, carrying placards and banging metal pans. At 10 a.m. a furious crowd of around 500, led by the volunteer firemen of Engine Company 33 (known as the “Black Joke”), attacked the assistant Ninth District provost marshal’s office, at Third Avenue and 47th Street, where the draft was taking place. The crowd threw large paving stones through windows, burst through the doors, and set the building ablaze. When the fire department responded, rioters broke up their vehicles. Others killed horses that were pulling streetcars and smashed the cars. To prevent other parts of the city being notified of the riot, they cut telegraph lines. They uprooted train tracks, and fashioned clubs from fence rails. The anti-draft zealots then went on an arson spree, targeting homes of draft supporters, well-known Republicans, and the wealthy on Fifth Avenue, looting as they went. Irish Catholic rioters targeted Protestant charities, such as the Magdalene Asylum and Five Points Mission. By the late afternoon, protesters had entered the city’s arsenal, which they burned (killing ten of their own) when the police arrived.

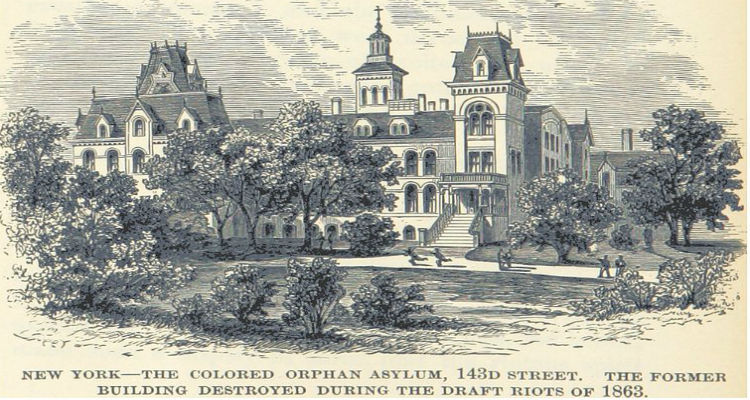

Many of the rioters were Irish laborers who feared having to compete with emancipated African-Americans for jobs, hence they started attacking African-Americans, shouting racial slurs, and torching homes of poor African Americans on the west side of 30th Street. In one of the most infamous incidents, a mob burned the Colored Orphan Asylum on west 44th Street, although its 237 children escaped to safety. The policy of racial extermination escalated during the night: a man was lynched and set afire; while waterfront tenements, taverns, and other others buildings populated by African-American laborers were systematically burned.

At Newspaper Row, across from City Hall, Henry Raymond, owner and editor of The New York Times, averted the rioters with Gatling guns, one of which he manned. The mob, instead, attacked the headquarters of abolitionist Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune until forced to flee by the Brooklyn Police.

On Tuesday, July 14, the rioters again focused on destroying and looting property of the wealthy, including stores such as Brooks Brothers. The protesters assaulted police and soldiers, who represented federal authority, and erected barricades along First and Third Avenues. The mob continued venting its ferocious fury on African-Americans, beating them and burning their homes and businesses. Yet, some of the anti-draft protesters, especially the German Americans, broke ranks with rioters and even assisted the police.

Democratic politicians essentially reacted with a policy of appeasement. Governor Seymour sent representatives to negotiate with the rioters, while addressing a group of protesters as “My friends,” and pledging to work for repeal of the draft. Republicans, on the other hand, called for swift and forceful action. “Crush the Mob!” ran The New York Times headline, as Mayor George Opdyke telegraphed Secretary of War Edwin Stanton for federal troops. Since Robert E. Lee, the invading Confederate commander, had crossed back into Virginia following his defeat at Gettysburg, Stanton was able to dispatch five regiments to New York City.

The federal troops arrived on Wednesday, July 15, as the demonstrators continued attacking African-Americanss, the wealthy, Protestant missions, and Republicans (who were identified with the previous three groups). Fierce fighting between soldiers and their allies and the rioters lasted until Thursday evening, July 16. By Friday, 6000 soldiers were dispersed throughout the city, and the situation began returning to normal. Similar anti-draft riots occurred in other Northern cities during the summer of 1863, but none as massive and destructive as the one in New York City.

Following the riot, President Lincoln appointed General John Dix, a War Democrat, to ensure that the military draft was implemented and that the city remained at peace. The prosecuting district attorney, Abraham Oakey Hall, and the presiding judge, John Hoffman, both Tammany Hall Democrats, earned praise from all sides for conducting rigorous yet fair trials. 67 of the indicted rioters were convicted, although few received long sentences.

Meanwhile, Lincoln reduced New York’s draft quota by more than half. The city’s Board of Supervisor’s, William Tweed’s Tammany Hall, and other organizations began hiring military substitutes for the city’s workingmen who could not otherwise afford them. The draft riot caused many Blacks to flee the metropolis, resulting in a 20% decline in New York City’s African-American population during the Civil War.

Source:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_York_City_draft_riots

http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/harp/0801.html

1 comment

I walk passed many of the spots mentioned in the article and of course it’s all wiped away due to progress but I look for the footprints of the buildings, etc. One of the most striking things about these accounts is the details of what happened to the women. Always the men talking and writing and reporting but NEVER about the hell that women endured in this. Too much goes unsaid. Excellent article but so much is missing. Would love to trace a few of the families driven out, those who stayed and those who did the driving out. I met up with one lady sitting on the steps of the old Customs House on Broadway and the ghosts must have connected us because she told me her family members were living in the Points then and hid Black kids under their skirts and scurried them off to safety towards boats to New Jersey or Brooklyn. She now lives in California. We don’t see the city the way it should be seen.

I truly love your site.