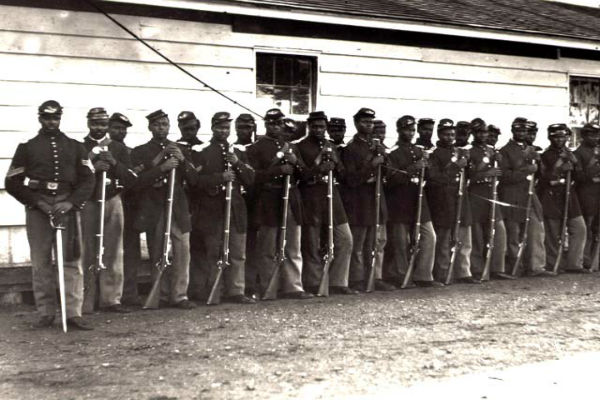

The United States Colored Troops (USCT) were regiments in the United States Army composed of African-American (colored) soldiers; they were first recruited during the American Civil War (1861-65), and by the end of that war in April, 1865, the 175 USCT regiments constituted about one-tenth the manpower of the Union Army.

The Massachusetts 54th Regiment is the best-known of the USCT regiments during the Civil War, and the subject of the 1989 feature film, Glory. Frederick Douglass’s two sons, Charles and Lewis were among the earliest African American volunteers accepted into the Union Army, and both served in the Massachusetts 54th Regiment. Lewis rose to the rank of sergeant major.

The regiment was authorized in March 1863 by the Governor of Massachusetts, John A. Andrew. Secretary of War, after the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, decided that whyte officers would be in charge of all African American units, therefore, the 54th was commanded by Colonel Robert Gould Shaw.

The 54th trained at Camp Meigs in Readville near Boston. Although Jefferson Davis’ proclamation of December 23, 1862, effectively put African-American enlisted men under a death sentence if captured, more recruits were coming forward than were needed. The medical exam for the 54th was described as “rigid and thorough” by the Massachusetts Surgeon-General and resulted in what he described as the most “robust, strong and healthy set of men” ever mustered into service in the United States.

The 54th left Boston with fanfare on May 28, 1863, and arrived to more celebrations in Beaufort, South Carolina, where they joined with the 2nd South Carolina Volunteers, a unit of South Carolina freedmen led by James Montgomery. After the 2nd Volunteers’ successful Raid at Combahee Ferry, Montgomery led both units in a raid on the town of Darien, Georgia. The population had fled, and Montgomery ordered the soldiers to loot and burn the empty town. Shaw objected to this activity and complained over Montgomery’s head that burning and looting were not suitable activities for his model regiment.

The 54th’s first battlefield action took place in a skirmish with Confederate troops on James Island, South Carolina, on July 16. Stopping a Confederate assault, the 54th lost 42 men in the process.

The 54th is remembered for it’s assault on Fort Wagner, South Carolina on July 18, 1863. 272 of the 600 men who charged Fort Wagner were “killed, wounded or captured.” At this battle Colonel Shaw was killed, along with 29 of his men; 24 more later died of wounds, 15 were captured, 52 were missing in action and never accounted for, and 149 were wounded. The total regimental casualties of 272 would be the highest total for the 54th in a single engagement during the war.

Although the 54th lost almost half its men and finally had to retreat, the regiment was widely acclaimed for its valor during the battle, which dramatized Black men’s fitness for the war. The event helped encourage the further enlistment and mobilization of African-American troops, a key development that President Abraham Lincoln once noted as helping to secure the final victory.

After this battle, Lewis Douglass wrote his fiancee that “this regiment has established its reputation…not a man flinched, though it was a trying time. Men fell all around me. A shell explode and clear a space of twenty feet, our men would close up again…”

Decades later, Sergeant William Harvey Carney was awarded the Medal of Honor for grabbing the U.S. flag as the flag bearer fell, carrying the flag to the enemy ramparts and back, and singing “Boys, the old flag never touched the ground!” While other African Americans had since been granted the award by the time it was presented to Carney, Carney’s is the earliest action for which the Medal of Honor was awarded to an African American.

After Shaw’s death at Fort Wagner, the 54th came under the command of Colonel Edward Hallowell. They fought a rear-guard action covering the Union retreat at the Battle of Olustee. During the retreat, the unit was suddenly ordered to counter-march back to Ten-Mile station. The locomotive of a train carrying wounded Union soldiers had broken down and the wounded were in danger of capture. When the 54th arrived, the men attached ropes to the engine and cars and manually pulled the train approximately three miles to Camp Finnegan, where horses were secured to help pull the train. After that, the train was pulled by both men and horses to Jacksonville for a total distance of ten miles. It took forty-two hours to pull the train that distance.

As part of an all-Black brigade under Col. Alfred S. Hartwell, they unsuccessfully attacked entrenched Confederate militia at the November 1864 Battle of Honey Hill. In mid-April 1865, they fought at the Battle of Boykin’s Mill, a small affair in South Carolina that proved to be one of the last engagements of the war.

Pay Controversy

The enlisted men of the 54th were recruited on the promise of pay and allowances equal to their whyte counterparts. This was supposed to amount to subsistence and $14 a month. Instead, they were informed upon arriving in South Carolina, the Department of the South would pay them only $7 per month ($10 with $3 withheld for clothing, while whyte soldiers did not pay for clothing at all.) Colonel Shaw and many others immediately began protesting the measure. Although the state of Massachusetts offered to make up the difference in pay, on principle, a regiment-wide boycott of the pay tables on paydays became the norm.

Refusing their reduced pay became a point of honor for the men of the 54th. In fact, at the Battle of Olustee, when ordered forward to protect the retreat of the Union forces, the men moved forward shouting, “Massachusetts and Seven Dollars a Month!”

The Congressional bill, enacted on June 16, 1864, authorized equal and full pay to those enlisted troops who had been free men as of April 19, 1861. Of course not all the troops qualified. Colonel Hallowell, a Quaker, rationalized that because he did not believe in slavery he could therefore have all the troops swear that they were free men on April 19, 1861. Before being given their back pay the entire regiment was administered what became known as “the Quaker oath.” Colonel Hallowell skillfully crafted the oath to say: “You do solemnly swear that you owed no man unrequited labor on or before the 19th day of April 1861. So help you God.”

On September 28, 1864, the U.S. Congress took action to pay the men of the 54th. Most of the men had served 18 months.

Legacy

A monument, constructed 1884–1898 by Augustus Saint-Gaudens on the Boston Common, is part of the Boston Black Heritage Trail.

New concerns for African Americans in the Civil War led to the creation of the African American Civil War Memorial and Freedom Foundation Museum in Washington D.C., in 1998 and 1999.

The story of the 54th was depicted in the 1989 Academy Award-winning film Glory, starring Matthew Broderick as Shaw, Denzel Washington as Private Tripp, Morgan Freeman, Cary Elwes, Jihmi Kennedy and Andre Braugher. The film showed the heroism of the Massachusetts 54th Regiment and re-established the now-popular image of the combat role African Americans played in the Civil War. This led to the 54th being called the “Glory” regiment.

Source:

Creating Black Americans by Nell Irvin Painter

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/54th_Massachusetts_Infantry_Regiment