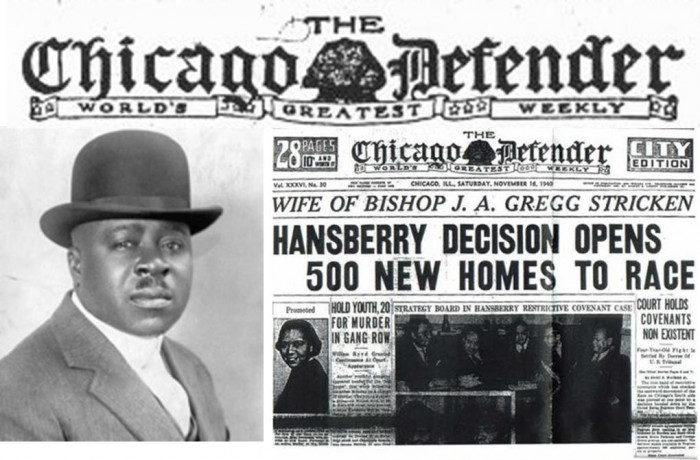

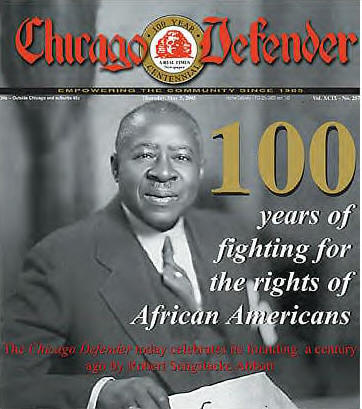

The Chicago Defender was the United States’ most influential Black weekly newspaper by the advent of World War I, with more than two thirds of its readership base located outside of Chicago. It was founded by Robert S. Abbott on May 5, 1905 and once heralded itself as “The World’s Greatest Weekly.” Its commitment to safeguarding civil liberties opened a new space for blacks to air their views and to voice their discontent. Abbott’s conviction that “American Race Prejudice must be destroyed” led the Defender to fight against racial, economic, and social discrimination, baldly reporting on lynching, rape, mob violence, and black disfranchisement. It championed fair housing and equal employment and was a chief proponent of the “spend your money where you can work” campaign.

Abbott began his journalistic enterprise with an initial investment of 25 cents, a press run of 300 copies and worked out of the dining room of his landlady, who supported him during the first years of operation. The paper was initially a four-page weekly that Abbott peddled from door to door on the South Side of Chicago. Through his work with the Defender, Abbott began a new phase in black journalism. He did not appeal primarily to educated African Americans, as earlier black newspapers had, but sought to make the paper accessible to the majority of blacks.

In 1910 Abbott hired his first full-time paid employee, J. Hockley Smiley, and with his help The Defender began to attract a national audience and to address issues of national scope. Smiley incorporated yellow journalism techniques similar to those used by William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer into the paper in order to boost sales and to dramatize various racial injustices in America. As a northern paper, The Defender had more freedom to denounce issues outright, and its editorial position was very militant, attacking racial inequities head-on. Sensationalistic headlines, graphic images, and red ink were utilized to capture the reader’s attention and convey the horrors of lynchings, rapes, assaults, and other atrocities affecting black Americans.

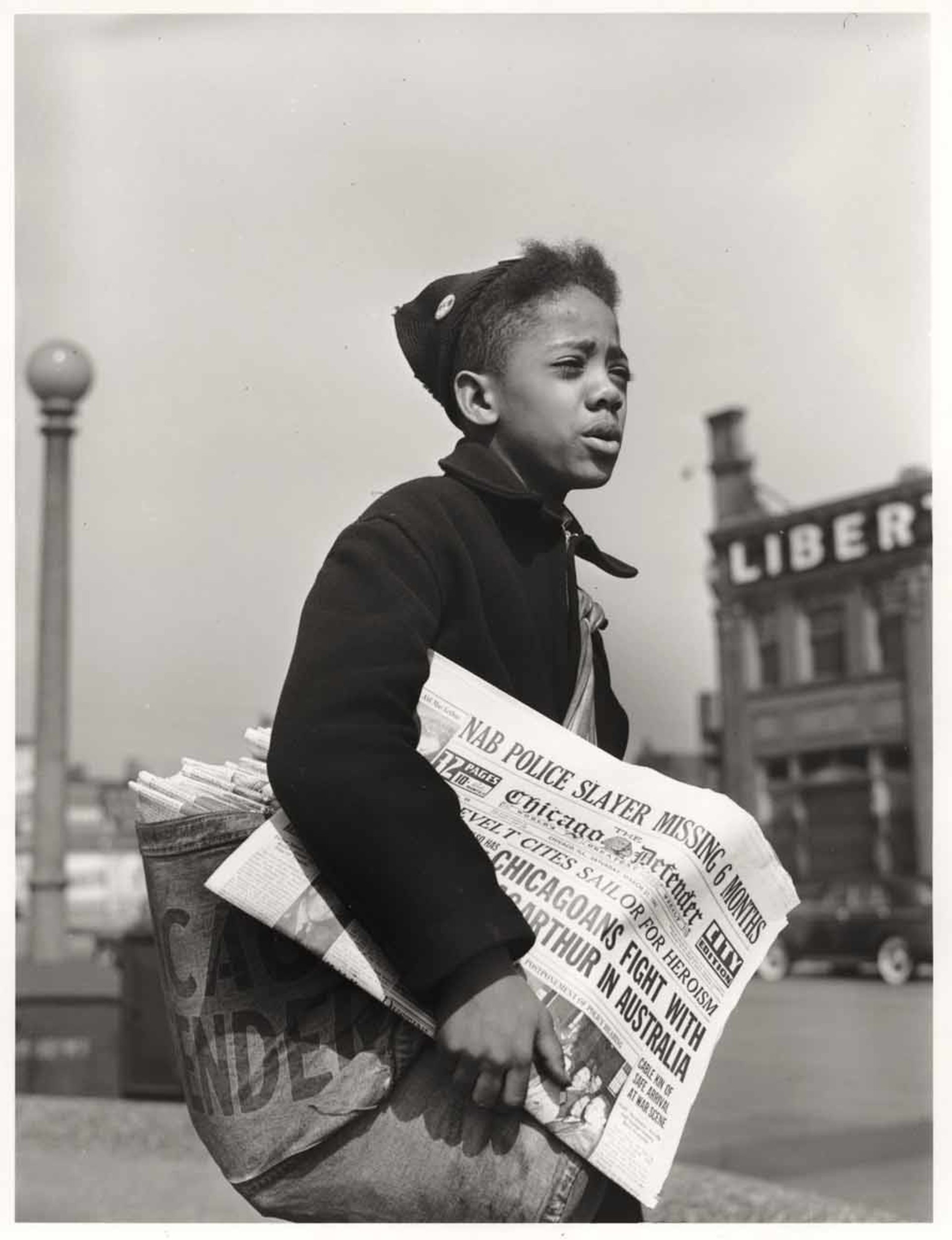

The Chicago Defender gained national prominence during the Great Migration during World War I, when large numbers of African Americans left the South to move North. The Defender did not use the words “Negro” or “black” in its pages. Instead, African Americans were referred to as “the Race” and black men and women as “Race men and Race women.” The Chicago Defender’s local circulation soon surpassed that of the three rival papers that existed in the Chicago area at that time: The Broad Ax, The Illinois Idea, and The Conservator. The newspaper was read extensively in the South. Black Pullman porters and entertainers were used to distribute the paper across the Mason/Dixon line. The paper was smuggled into the south because whyte distributors refused to circulate The Defender and many groups such as the Klu Klux Klan tried to confiscate it or threatened its readers. The Defender was passed from person to person, and read aloud in barbershops and churches. It is estimated that at its height each paper sold was read by four to five African Americans, putting its readership at over 500,000 people each week. The Chicago Defender was the first black newspaper to have a circulation over 100,000, the first to have a health column, and the first to have a full page of comic strips.

The paper covered brutal incidents of racism in the South and encouraged African Americans to leave the rigid segregation, poor pay, and violence of the South. In 1915, in response to the rising incidence of lynching, the Defender advised, “If you must die, take at least one with you.” It promised better-paying jobs and more freedom in northern cities. Many black southerners wrote to the Defender asking for job-placement help. The Defender also tried to address the problems of migrants by helping form clubs that arranged reduced rates on the railroad. It counseled newly arrived African Americans, helped them find jobs, and sent them to the appropriate relief and aid agencies. To alleviate the acute housing shortage, the Defender supported the construction of housing for African Americans and opposed restrictive covenants. Although Abbott decried World War I as “bloody, tragic, and deplorable,” he believed there were some benefits from it for African Americans, noting that “Factories, mills, and workshops that have been closed to us through necessity are being opened to us. We are to be given a chance.”

Like most newspapers, the Defender was hurt by the Great Depression. By 1935 circulation had dropped to 73,000. It continued to cover black civil rights issues, but also included cartoons, personals, and social, cultural, and fashion articles. In 1939, the year before he died, Abbott passed control of the paper to his nephew John Sengstacke. Under Sengstacke’s leadership, the Defender continued to be an advocate for social and economic justice. During World War II, its editors wrote, “In pledging our allegiance to the flag and what it symbolizes we are not unmindful of the broken promises of the past. We ask that America give the Negro citizen the full measure of the democracy he is called upon to defend.” The paper covered the racial violence and riots during the war but made a special effort to see that its coverage was not provocative. Editors refused, for example, to publish photographs of the 1943 Harlem Riot. In 1945 its total Chicago and national circulation was 160,000. In 1956 the paper became a tabloid issued four times a week with a national weekend edition.

The Defender was noted for the quality of its writers, among them novelist Willard Motley, poet Gwendolyn Brooks, and Langston Hughes, whose “Simple” stories first appeared in 1942 in the Defender column he wrote for more than 20 years. After Sengstacke’s death in 1997, however, the Defender’s national influence diminished, with circulation declining to less than 20,000. In 2003 the newspaper was bought by Real Times, a company controlled by one of Sengstacke’s relatives.

Sources:

http://www.pbs.org/blackpress/news_bios/defender.html

http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/248.html

http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Chicago_Defender.aspx

http://www.britannica.com/topic/Chicago-Defender