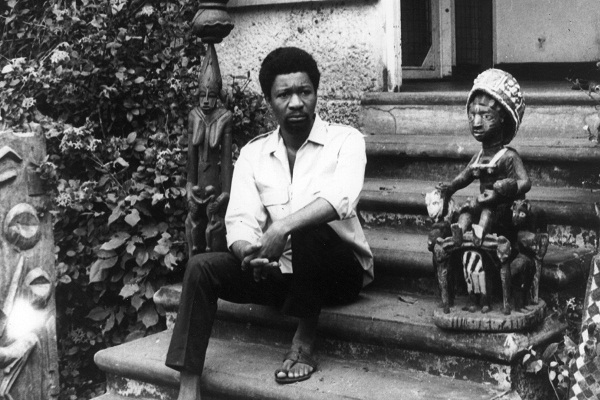

Akinwande Oluwole “Wole” Babatunde Soyinka, born 13 July 1934, is a Nigerian playwright and poet. He was the first African to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1986, and two of his works, the play Death and the King’s Horseman and Aké: Years of Childhood, an autobiographical account of his childhood, were listed in Africa’s 100 Best Books of the 20th Century. He has spent long periods in political exile.

Wole Soyinka was born Akinwande Oluwole “Wole” Babatunde Soyinka on July 13, 1934, the second of six children, in Abeokuta, near Ibadan in western Nigeria. His father, Samuel Ayodele Soyinka, was a prominent Anglican minister and headmaster. His mother, Grace Eniola Soyinka, whom he dubbed the “Wild Christian”, owned a shop in the nearby market and was a political activist within the women’s movement in the local community. As a child, he lived in an Anglican mission compound, learning the Christian teachings of his parents, as well as the Yoruba spiritualism and tribal customs of his grandfather. Hence, Soyinka grew up in an atmosphere of religious syncretism, with influences from both cultures. A precocious and inquisitive child, Wole prompted the adults in his life to warn one another: “He will kill you with his questions.”

After finishing preparatory university studies in 1954 at Government College in Ibadan, Soyinka moved to England and continued his education at the University of Leeds, where he served as the editor of the school’s magazine, The Eagle. He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in English literature in 1958. (In 1972 the university awarded him an honorary doctorate).

In the late 1950s Soyinka wrote his first important play, A Dance of the Forests, which satirized the Nigerian political elite. From 1958 to 1959, Soyinka was a dramaturgist at the Royal Court Theatre in London. In 1960, he was awarded a Rockefeller fellowship and returned to Nigeria to study African drama.

In 1960, he founded the theater group, The 1960 Masks, and in 1964, the Orisun Theatre Company, in which he produced his own plays and performed as an actor. He has periodically been a visiting professor at the universities of Cambridge, Sheffield, and Yale.

Soyinka is also a political activist. He took an active role in Nigeria’s political history and its struggle for independence from Great Britain. In 1965, he seized the Western Nigeria Broadcasting Service studio and broadcast a demand for the cancellation of the Western Nigeria Regional Elections, and during the civil war in Nigeria he appealed in an article for a cease-fire. He was arrested for this in 1967 and held as a political prisoner for 22 months until 1969. Though refused materials such as books, pens, and paper, he still wrote a significant body of poems and notes criticizing the Nigerian government.

Despite his imprisonment, in September 1967, his play The Lion and The Jewel was produced in Accra. In November The Trials of Brother Jero and The Strong Breed were produced in the Greenwich Mews Theatre in New York. He also published a collection of his poetry, Idanre and Other Poems. It was inspired by Soyinka’s visit to the sanctuary of the Yorùbá deity Ogun, whom he regards as his “companion” deity, kindred spirit, and protector. In 1968, the Negro Ensemble Company in New York produced Kongi’s Harvest. While still imprisoned, Soyinka translated from Yoruba a fantastical novel by his compatriot D. O. Fagunwa, entitled The Forest of a Thousand Demons: A Hunter’s Saga.

In October 1969, when the civil war came to an end, amnesty was proclaimed, and Soyinka and other political prisoners were freed. For the first few months after his release, Soyinka stayed at a friend’s farm in southern France, where he sought solitude. He wrote The Bacchae of Euripides (1969), a reworking of the Pentheus myth.[22] He soon published in London a book of poetry, Poems from Prison. At the end of the year, he returned to his office as Headmaster of Cathedral of Drama in Ibadan, and cooperated in the founding of the literary periodical Black Orpheus (likely named after the 1959 film directed by Marcel Camus and set in the favela of Rio de Janeiro).

In 1970 he produced the play Kongi’s Harvest, while simultaneously adapting it as a film of the same title. In June 1970, he finished another play, called Madman and Specialists. Together with the group of 15 actors of Ibadan University Theatre Art Company, he went on a trip to the United States, to the Eugene O’Neill Memorial Theatre Center in Waterford, Connecticut, where his latest play premiered. It gave them all experience with theatrical production in another English-speaking country.

In 1971, his poetry collection A Shuttle in the Crypt was published. Madmen and Specialists were produced in Ibadan that year. Soyinka traveled to Paris to take the lead role as Patrice Lumumba, the murdered first Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo, in the production of his Murderous Angels. His powerful autobiographical work The Man Died(1971), a collection of notes from prison, was also published.

In April 1971, concerned about the political situation in Nigeria, Soyinka resigned from his duties at the University in Ibadan and began years of voluntary exile. In July in Paris, excerpts from his well-known play The Dance of The Forests were performed.

In 1972, he was awarded an Honoris Causa doctorate by the University of Leeds. Soon thereafter, his novel Season of Anomy (1972) and his Collected Plays (1972) were both published by Oxford University Press. In 1973 the National Theatre, London, commissioned and premiered the play The Bacchae of Euripides. In 1973 his plays Camwood on the Leaves and Jero’s Metamorphosis were first published. He also wrote Death and the King’s Horseman, which had its first reading at Churchill College, and gave a series of lectures at a number of European universities.

In 1974 his Collected Plays, Volume II was issued by Oxford University Press. In 1975 Soyinka was promoted to the position of editor for Transition, a magazine based in the Ghanaian capital of Accra, where he moved for some time. He used his columns in Transition to criticise the “negrophiles” and military regimes. After the political turnover in Nigeria and the subversion of Gowon’s military regime in 1975, Soyinka returned to his homeland and resumed his position at the Cathedral of Comparative Literature at the University of Ife.

In 1976 he published his poetry collection Ogun Abibiman, as well as a collection of essays entitled Myth, Literature and the African World. In these, Soyinka explores the genesis of mysticism in African theatre and, using examples from both European and African literature, compares and contrasts the cultures. He delivered a series of guest lectures at the Institute of African Studies at the University of Ghana in Legon. In October, the French version of The Dance of The Forests was performed in Dakar, while in Ife, his Death and The King’s Horseman premiered.

In 1977 Opera Wọnyọsi, his adaptation of Bertold Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera, was staged in Ibadan. In 1979 he both directed and acted in Jon Blair and Norman Fenton’s drama The Biko Inquest, a work based on the life of Steve Biko, a South African student and human rights activist who was beaten to death by apartheid police forces. In 1981 Soyinka published his autobiographical work Aké: The Years of Childhood, which won a 1983 Anisfield-Wolf Book Award.

Soyinka founded another theatrical group called the Guerrilla Unit. Its goal was to work with local communities in analyzing their problems and to express some of their grievances in dramatic sketches. In 1983 his play Requiem for a Futurologist had its first performance at the University of Ife. In July, one of Soyinka’s musical projects, the Unlimited Liability Company, issued a long-playing record entitled I Love My Country, on which several prominent Nigerian musicians played songs composed by Soyinka. In 1984, he directed the film Blues for a Prodigal; his new play A Play of Giants was produced the same year.

During the years 1975–84, Soyinka was also more politically active. At the University of Ife, his administrative duties included the security of public roads. He criticized the corruption in the government of the democratically elected President Shehu Shagari. When he was replaced by General Muhammadu Buhari, Soyinka was often at odds with the military. In 1984, a Nigerian court banned his 1971 book The Man Died. In 1985, his play Requiem for a Futurologist was published in London by André Deutsch.

In 1986, upon awarding Soyinka with the Nobel Prize for Literature, the committee said the playwright “in a wide cultural perspective and with poetic overtones fashions the drama of existence.” Soyinka sometimes writes of modern West Africa in a satirical style, but his serious intent and his belief in the evils inherent in the exercise of power are usually present in his work. To date, Soyinka has published hundreds of works.

In addition to drama and poetry, he has written two novels, The Interpreters (1964) and Season of Anomy (1972), as well as autobiographical works including The Man Died: Prison Notes (1971), a gripping account of his prison experience, and Aké ( 1981), a memoir about his childhood. Myth, Literature and the African World (1975) is a collection of Soyinka’s literary essays.

With civilian rule restored to Nigeria in 1999, Soyinka returned to his nation. He is now considered Nigeria’s foremost man of letters and is still politically active.

Soyinka has been married three times. He married British writer Barbara Dixon in 1958; Olaide Idowu, a Nigerian librarian, in 1963; and Folake Doherty, his current wife, in 1989. In 2014, Soyinka revealed he was diagnosed with prostate cancer and cured 10 months after treatment.

Wole Soyinka’s works

[column size=one_half position=first ]

- Plays

- “Keffi’s Birthday Treat” (1954)

- The Invention (1957)

- The Swamp Dwellers (1958)

- A Quality of Violence (1959)[50]

- The Lion and the Jewel (1959)

- The Trials of Brother Jero

- A Dance of the Forests (1960)

- My Father’s Burden (1960)

- The Strong Breed (1964)

- Before the Blackout (1964)

- Kongi’s Harvest (1964)

- The Road (1965)

- Madmen and Specialists (1970)

- The Bacchae of Euripides (1973)

- Camwood on the Leaves (1973)

- Jero’s Metamorphosis (1973)

- Death and the King’s Horseman (1975)

- Opera Wonyosi (1977)

- Requiem for a Futurologist (1983)

- Sixty-Six (short piece) (1984)[51]

- A Play of Giants (1984)

- From Zia with Love (1992)

- The Detainee (radio play)

- A Scourge of Hyacinths (radio play)

- The Beatification of Area Boy (1996)

- Document of Identity (radio play, 1999)

- King Baabu (2001)

- Etiki Revu Wetin

- “Alapata Apata” (2011)

- Novels

- The Interpreters (1964)

- Season of Anomy (1972)

- Short stories

- A Tale of Two (1958)

- Egbe’s Sworn Enemy (1960)

- Madame Etienne’s Establishment (1960)

- Memoirs

- The Man Died: Prison Notes (1971)

- Aké: The Years of Childhood (1981)

- Ibadan: The Penkelemes Years: a memoir 1946-65 (1989)

[/column]

[column size=one_half position=last ]

- Isara: A Voyage around Essay (1990)

- You Must Set Forth at Dawn (2006)

- Poetry collections

- Idanre and other poems (1967)

- A Big Airplane Crashed Into The Earth (original title Poems from Prison) (1969)

- A Shuttle in the Crypt (1971)

- Ogun Abibiman (1976)

- Mandela’s Earth and other poems (1988)

- Early Poems (1997)

- Samarkand and Other Markets I Have Known (2002)

- Essays

- Towards a True Theater (1962)

- Culture in Transition (1963)

- Neo-Tarzanism: The Poetics of Pseudo-Transition

- Art, Dialogue, and Outrage: Essays on Literature and Culture (1988)

- From Drama and the African World View (1976)

- Myth, Literature, and the African World (1976)[52]

- The Blackman and the Veil (1990)[53]

- The Credo of Being and Nothingness (1991)

- The Burden of Memory – The Muse of Forgiveness (1999)

- A Climate of Fear (originally held as the BBC Reith Lectures 2004, audio and transcripts)

- New Imperialism (2009)[54]

- Of Africa (2012)[55][56]

- Movies

- Kongi’s Harvest

- Culture in Transition

- Blues for a Prodigal

- Translations

- The Forest of a Thousand Demons: A Hunter’s Saga (1968; a translation of D. O. Fagunwa’s Ògbójú Ọdẹ nínú Igbó Irúnmalẹ̀)

- In the Forest of Olodumare (2010; a translation of D. O. Fagunwa’s Igbo Olodumare)

[/column]

Source:

http://www.biography.com/people/wole-soyinka-9489566#synopsis

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wole_Soyinka