Vivian Juanita Malone Jones was one of the first two African American students to enroll at the University of Alabama in 1963 and the university’s first African American graduate. She was made famous by defying Alabama Governor George Wallace’s infamous “stand in the schoolhouse door” to block her and James Hood from enrolling at the all-whyte university. Her entrance to the university came as the civil rights struggle raged across the South. On June 12, the day after Malone and Hood were escorted into the university by federalized National Guard troops, the civil rights leader Medgar Evers was assassinated.

Vivian Malone was born on July 15, 1942, and grew up in Mobile, Alabama, the oldest of eight children. Her parents both worked at Brookley Air Force Base; her father served in maintenance and her mother worked as a domestic servant. Her parents emphasized the importance of receiving an education and made sure that their children attended college. Each of Malone’s older brothers attended Tuskegee University. Her parents were also active in civil rights and often participated in local meetings, donations, and activities in the community that promoted equality and desegregation. As a teenager, Vivian was often involved in community organizations to end racial discrimination and worked closely with local leaders of the movements to work for desegregation in schools.

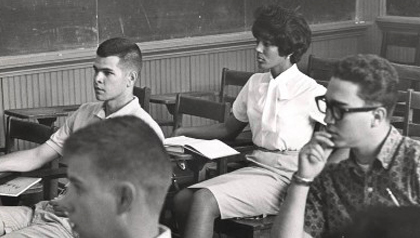

Malone attended Central High School, where she was a member of the National Honor Society. In February 1961, she enrolled in Alabama Agricultural and Mechanical University, one of the few colleges for Black students in the state. She attended Alabama A&M for two years and received a Bachelor’s degree in Business Education before the University had been fully accredited. To get an accredited degree, she applied to the University of Alabama’s School of Commerce and Business Administration. As a transfer student, she was 20 when she and Hood were admitted to the University of Alabama. They had to wait four and a half hours after Wallace’s initial refusal to be admitted to the university, only after the federalized guard troops arrived. Wallace read a second statement challenging the constitutionality of the court order, then briskly left. The students entered Foster Hall, registered, went to their dormitories, ate in the cafeteria, and experienced no further incidents that day.

One night at midnight, someone knocked on her dormitory door and told her there was a bomb threat. No bomb materialized, but that November, there were three bomb blasts at the university, one of them, four blocks from her dormitory. “I was never afraid,” she recalled. “I did have some apprehension in my mind, though, especially having gone to segregated ‘separate but equal’ schools.” Hood left the university after two months “to avoid a breakdown,” transferring to Wayne State University in Detroit and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in political science and police administration. He returned to the University of Alabama in 1997 to take a doctorate in higher education.

After Evers’ murder, Malone said she felt even more determined not to give up. “I decided not to show any fear and went to classes that day,” she said in an interview with The Post Standard of Syracuse in 2004. In the same interview, she said that one of her strongest memories was of how whyte students refused to make eye contact with her or return her smile. She credited her solid upbringing and strong religious belief for the strength to challenge segregation, having set her mind simply on “going to class and doing the best I could”.

The university hired a driver for her, a student at Stillman College in Tuscaloosa named Mack Jones. They later married, and he became an obstetrician.

On May 30, 1965, Malone became the first Black to graduate from the University of Alabama in its 134 years of existence, earning a degree in business management with a B-plus average.

(The first African-American at the university, founded in 1831, was Autherine Lucy, who arrived in February 1956 to pursue a master’s degree in library science. But after experiencing three days of threats Ms. Lucy was suspended, ostensibly for her own safety, and later expelled.)

After graduation, Malone had difficulty finding work in Alabama. She moved to Washington to work in the civil rights division of the US justice department, and later became director of civil rights and urban affairs, and director of environmental justice, at the environmental protection agency. She retired in 1996.

In 1996, former Governor Wallace presented the Lurleen B. Wallace Award for Courage, named for his late wife, to Malone. He told her that he made a mistake 33 years earlier and that he admired her. They discussed forgiveness.

In a speech to University of Alabama graduates in 2000, Ms. Jones suggested one lesson that might be taken from her historic experience: “You must always be ready to seize the moment.”

Source:

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/10/14/us/vivian-malone-jones-63-dies-first-black-graduate-of-university-of-alabama.html?_r=0

http://www.theguardian.com/news/2005/oct/18/guardianobituaries.usa

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vivian_Malone_Jones