“I wanted to understand my people. I wanted to understand what it meant to be a [Black]. What the qualities of life were. With their imagination, they combine two great loves: the love of words and the love of life. Poetry results.”

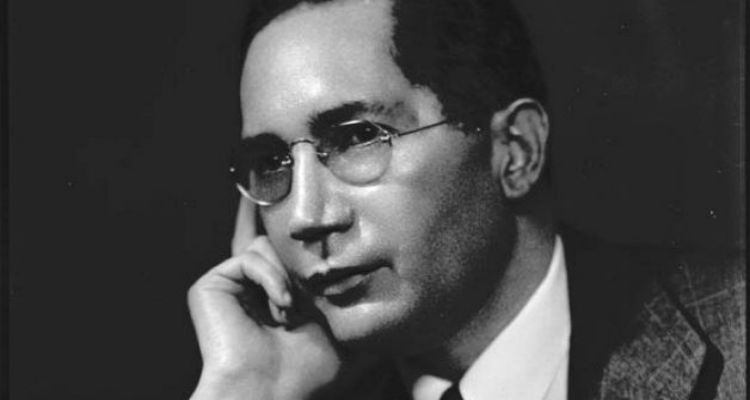

Sterling Allen Brown was an African American professor, literary critic, folklorist, and poet, best known for writing poetry distinctly rooted in folklore and authentic Black dialect. Brown who worked as a full professor at Howard University for most of his career, was one of the first scholars to identify folklore as a vital component of the Black aesthetic and to recognize its validity as a form of artistic expression. Brown’s influence in the field of African-American literature has been so great that scholar Darwin T. Turner told Ebony Magazine: “I discovered that all trails led, at some point to Sterling Brown. His Negro Caravan was the anthology of Afro-American. His unpublished study of Afro-American theater was the major work in the field. His study of images of Afro-Americans in American literature was a pioneer work. His essays on folk literature and folklore were preeminent. He was not always the best critic…but Brown was the literary historian who wrote the Bible for the study of Afro-American literature.”

Sterling Allen Brown was born in Washington, D.C., on May 1, 1901. He was born on Howard University’s campus, as the sixth child, and only son of schoolteacher Adelaide Allen and her husband, distinguished theologian and divinity school professor Sterling Nelson Brown. Brown graduated with honors from the prestigious Dunbar High School in 1918. That fall, he attended Williams College on a scholarship, and distinguished himself by winning the Graves Prize for his essay “The Comic Spirit in Shakespeare and Moliere”. Brown was the only student awarded “Final Honors” in English, and cum laude graduation with an AB degree. In 1923, he earned a master’s degree in English from Harvard University and embarked on a teaching career.

Brown took a job teaching English at the Virginia Seminary and College in Lynchburg, Virginia, at the urging of his father and historian Carter G. Woodson. Exposed to the rural population of the South, he discovered the essence of what he described as a “people’s poetry.” At Virginia Seminary, Brown befriended Calvin “Big Boy” Davis, an itinerant musician and singer who would later serve as the catalyst for several of Brown’s poetic works. “He was a treasure trove of stories, songs,” wrote Brown. “He was a wandering guitar player… He knew blues, ballads, spirituals. He had a fine repertoire, and he’d sing, and although all of us were on starvation wages, we’d hand him a little money, buy him something to drink… This wasn’t my introduction, but this was my deepening awareness of the importance of music.”

In 1925 Brown’s poem Roland Hayes, about the classical singer, became his first nationally published work, winning second prize in a contest sponsored by Opportunity magazine. Two years later, he won Opportunity’s first prize for the poem When de Saints Go Ma’ching Home, dedicated to Big Boy Davis. As the poem’s narrator, Big Boy roams the landscape, his memory pouring forth images and characters from places where, as Brown concludes in the poem’s last stanza, “we never could follow him.”

In 1926 Brown began a two-year teaching job at Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Missouri. Here, too, he spent time out of the classroom on “folklore collecting trips,” seeking out interesting individuals and local musicians.

Brown next taught at Fisk University where, from 1928 to 1929, where he continued his search for African American culture. He would often make trips to Nashville, Tennessee, to watch blues singer Bessie Smith perform. He lived in an apartment on campus with his wife, Daisy Turnbull, whom he had married in 1927. Despite his growing profile as a poet and writer, Brown remained committed to his career as a teacher. He took a position at Howard University in 1929 and two years later, enrolled in the University’s doctoral program.

Brown’s first collection of poems, Southern Road, was published in 1932.

According to most critics, Southern Road ushered in a new era of African American literary achievement. James Weldon Johnson’s introduction praised Brown for having, in effect, discovered how to write a Black vernacular poetry that was not fraught with the limitations of the “dialect verse” of the Paul Laurence Dunbar era thirty years earlier. Johnson wrote that Brown “has made more than mere transcriptions of folk poetry, and he has done more than bring to it mere artistry; he has deepened its meanings and multiplied its implications.” Southern Road was well received by critics and Brown became part of the artistic tradition of the Harlem Renaissance.

In addition to his career at Howard University, Brown also wrote a regular column for Opportunity (“The Literary Scene: Chronicle and Comment”), reviewed plays and films as well as novels, biographies, and scholarship by African and Euro Americans alike. From 1936 to 1939 Brown was the Editor on Negro Affairs for the Federal Writers’ Project. In that capacity he oversaw virtually everything written about African Americans and wrote large sections of The Negro in Virginia (1940), a work that led to his being named a researcher on the Carnegie-Myrdal Study of the Negro, which generated the data for Gunnar Myrdal’s classic study, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy (1944). In 1937 Brown was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, which afforded him the opportunity to complete The Negro in American Fiction and Negro Poetry and Drama, both published in 1937. The Negro Caravan: Writings by American Negroes (1941), a massive anthology of African-American writing, edited by Brown with Ulysses Lee and Arthur P. Davis, continues to be the model for bringing song, folktale, mother wit, and written literature together in a comprehensive collection.

From the 1940s into the 1960s Brown was no longer an active poet., as he was unable to find a publisher for his second collection, No Hiding Place; it eventually was incorporated into his Collected Poems (1980). Even though many of his poems were published in The Crisis, The New Republic, and The Nation, Brown turned to writing essays and focused on his career as a teacher at Howard, where he taught until his retirement in 1969. In the 1950s Brown published such major essays as “Negro Folk Expression,” “The Blues,” and “Negro Folk Expression: Spirituals, Seculars, Ballads and Work Songs,” all in the Atlanta journal Phylon. Also in this period Brown wrote “The New Negro in Literature (1925-1955)” (1955). In this essay he argued that the Harlem Renaissance was in fact a New Negro Renaissance, not a Harlem Renaissance, because few of the significant participants, including himself, lived in Harlem or wrote about it. He concluded that the Harlem Renaissance was the publishing industry’s hype, an idea that gained renewed attention when publishers once again hyped the Harlem Renaissance in the 1970s.

The 1970s and 1980s were a period of recognition when student interest sparked a revival of his work — his students included playwright Ossie Davis, political activist Stokely Carmichael and Nobel Prize–winning author Toni Morrison. Numerous invitations followed for poetry readings, lectures, tributes, and for fourteen honorary degrees. In 1974 Southern Road was reissued. In 1975, he finally published his second book of poetry, under the title The Last Ride of Wild Bill and Eleven Narrative Poems.

In 1979, the District of Columbia declared his birthday, May 1, Sterling A. Brown Day. “I’ve been rediscovered, reinstituted, regenerated and recovered,” he told The Washington Post. The Collected Poems of Sterling Brown, published in 1980, won the Lenore Marshall Prize, and Brown was named Poet Laureate of the District of Columbia in 1984, prompting The Washington Post to note that it was a designation “[he had] held informally for most of his 83 years.”

Sterling Brown died of leukemia at age 88 on January 13, 1989, in Takoma Park, Maryland.

In 1991, following a University-wide contest to name the Howard University Libraries’ new Online Public Access Catalog (OPAC), the name “Sterling” was selected to commemorate the unique contributions and far-reaching impact of Sterling Allen Brown.

Source

https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poet/sterling-brown

http://www.biography.com/people/sterling-brown-38153

http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/poets/a_f/brown/life.htm

http://www.founders.howard.edu/event1.html

http://www.encyclopedia.com/people/history/historians-miscellaneous-biographies/sterling-allen-brown