Quamina Gladstone, most often referred to simply as Quamina, was an enslaved Guyanese, a Coromantee, who was father of Jack Gladstone. Quamina and his son were involved in the Demerara rebellion of 1823, one of the largest Maafa revolts in the British colonies before Maafa (Slavery) was abolished.

Quamina was a carpenter who lived and worked on “Success” plantation in Demerara, an estate owned by Sir John Gladstone. Quamina was implicated in the revolt by the colonial authorities and was apprehended and executed on 16 September 1823. He is considered a national hero in Guyana, and there are streets in Georgetown and the village of Beterverwagting on the East Coast Demerara, named after him.

Quamina was African, born in Ghana in 1778. He and his mother were sold into Maafa when he was a child. His mother died on a plantation in 1817. He is surnamed Gladstone, as the enslaved people adopted surnames of their enslaver by convention. Sir John Gladstone, who had never set foot on his plantation, had acquired half share in the plantation in 1812 through mortgage default; he acquired the remaining half four years later.

Quamina attended services at the Bethel Chapel of the London Missionary Society on neighbouring Le Resouvenir plantation when the chapel opened in 1808. Under the guidance of Reverend John Wray, he learned to read and write. As was witnessed in a letter he wrote to the LMS, he was persuaded to attend the recently opened church by the person who he served as apprentice. Wray noticed positive changes after he became Christian. Quamina was proud and hardworking, and was baptised on 26 December 1808. On being assessed for fitness to become a member, Quamina declared that when he was young, he had been a houseboy and had to “fetch” girls to entertain the estate’s managers. When Wray was sent to nearby Berbice in 1816, his replacement Reverend John Smith was equally impressed by Quamina’s qualities. He took an interest in others, and had become widely respected by the enslaved people and free blacks throughout the colony. Quamina was one of five the enslaved elected deacon by the congregation during the month after Rev. John Smith had arrived at Le Resouvenir in 1817. Quamina became Smith’s personal favourite, and was highly trusted by Rev. Smith and his wife, Jane. The deacons played an important role in the mission. Quamina was the most loyal, well-behaved, trustworthy and pious of the deacons. He prayed with much emotion. He brought news of the congregation members on a day-to-day basis, and was always consulted about the affairs of any member. He reported to Rev. Smith in 1821, that Susanna, an enslaved woman, who was a member of the congregation and partner of Quamina’s son Jack Gladstone, had been “seduced” by Hamilton, the manager of Le Resouvenir. Rev. Smith and many of the members of the chapel disapproved of this relationship, and a meeting of the congregation decided to exclude her from the chapel.

Quamina became the head deacon at Bethel Chapel and was well respected. He had many wives, but he cohabited for twenty years with Peggy, a free woman. As was common with the enslaved, he had been harshly treated and humiliated by his enslaver and once was beaten badly and incapacitated for six weeks. He was frequently forced to work, thus missing religious services. In 1822, when Peggy was taken seriously ill, he was forced to work all day, every day, and was not allowed any time off to look after her. One evening, he returned to find her dead.

Being very close to his son Jack, Quamina supported his son’s aspirations to be free, by supporting the fight for the rights of the enslaved. But he was at the same time a rational man. He had been troubled for some time by rumours he had heard about an emancipation ordered by Britain that was being withheld by the colonists. Rev. Smith had noted that on 25 July 1823, Quamina had gone to see him and asked whether it was true that King George had sent orders to the Governor to free the enslaved. He noted that his response was that he had not heard this and that if such a report had been in circulation it was not to be believed. Smith assured him that any announcement would be of measures to improve the enslaved condition, and urged him to tell the others particularly the Christians, not to rebel and sent Manuel and Seaton on this mission. When he knew the rebellion was imminent, he urged restraint, and made the fellow enslaved promise a peaceful strike.

On Sunday 17 August, Quamina and a few others went to Rev. Smith’s house after service. Rev. Smith overheard talk about ‘new laws’ and when he asked them about their conversation, Quamina stated that they were only saying that it would be good to send their managers to the town “to fetch up the new law”. Smith advised against any such action and Quamina promised that they would do nothing. Following this, there was a large meeting of the enslaved people at Success Middle Walk, when decisions on strategy were made. Jack Gladstone took the lead. Some of the enslaved people wanted to rise against the planters, some wanted to hold a strike or other form of protest, and others wanted to wait. Quamina insisted the revolt should not involve killing and suggested that the enslaved people should go on strike. In the end, they decided to begin the uprising on Monday evening, to confine managers and overseers in the stocks and to seize their weapons and ammunition. Quamina tried to stop Jack and the others and urged them not to be violent in the process. They followed his advice and there was very little violence.

The uprising commenced at Success on the evening of Monday 18 August 1823, and extended to several plantations along the coast from Plantation Thomas, adjoining Georgetown, to Plantation Grove, at Mahaica. Out of an estimated 74,000 enslaved people it only involved about 13,000, many of them Christians. Over 9,000 had been proved to have participated, by the evidence given in several court trials, according to a despatch sent by Governor Murray to Earl Bathurst. And of the 350 plantations estates in the colony, only thirty-seven were involved. No doubt, many who did not take part sympathised with their fellow enslaved people and shared their suspicion that the planters would spare no efforts to prevent them from obtaining their freedom.

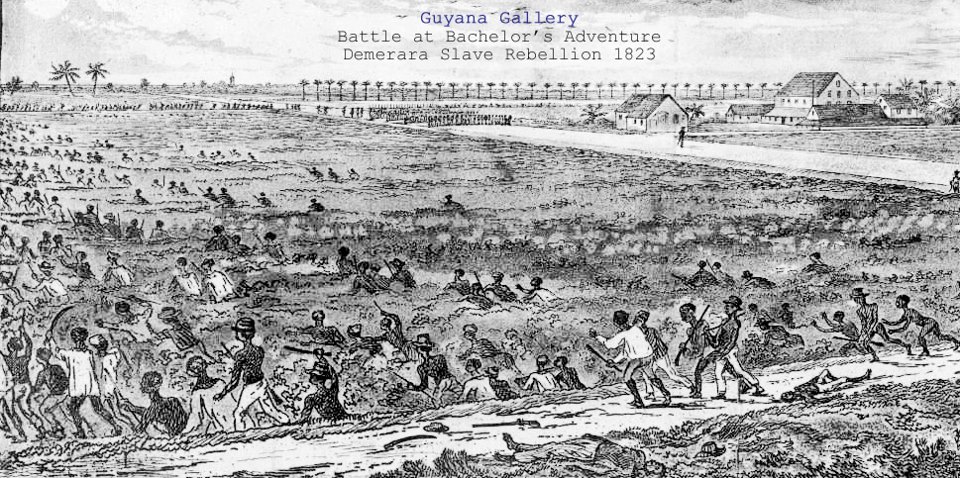

News of the planned rebellion had leaked out, and Quamina was arrested by John Stewart, the manager at his plantation, shortly before it was due to start. And although he was set loose by fellow enslaved people as the rebellion was unfolding, Quamina never took up arms, and even actively prevented Stewart from coming to any harm. On 20 August, the rebels were defeated by the colonial cavalry and the militia in a major battle at “Bachelor’s Adventure”, Jack fled into the woods. A reward of one thousand guilders was offered for the capture of Jack, Quamina and about twenty other men and ten women. Although Jack led thousands of slaves in rebellion, most of the colonists thought the reverse – that Quamina was the ultimate leader, and Jack was merely aiding and abetting it. Jack and his wife were captured by Capt. McTurk at Chateau Margo on 6 September after a three-hour standoff.

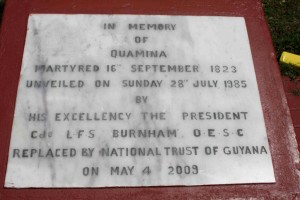

Quamina remained at large until he was captured on 16 September in the fields of Chateau Margo. He was then executed. He was first ordered to stop, but he neither stopped nor ran. He continued walking without looking back, as if he had not heard the order. He was then shot dead. A clasp knife and a Bible were found in his pockets. He was unarmed. His body was carried to Success, and was hung in chains on a gibbet erected on 17 September, on the road at the front of the plantation.

The very low number of white deaths is proof that the uprising was largely peaceful – plantation owners, managers and their families were locked up and not harmed. Hundreds of the enslaved died during the various battles and skirmishes during the revolt, or were executed as “ringleaders”. A report prepared by Governor John Murray two days later praised the troops and noted that only one soldier was slightly injured while noting that “100 to 150” slaves were shot dead. Jack Gladstone was sold and deported to Saint Lucia. The rebellion helped bring attention to the plight of sugar plantation enslaved people, accelerating the full abolition of Maafa (Slavery).

Quamina is considered a national hero in Guyana. In 1985 the post-independence Guyana renamed Murray Street in Georgetown — named for former Demerara Lieutenant Governor John Murray (1813–1824) who was in charge of the colony during the unrest and rebellion — Quamina Street in his honour. A monument to him was erected at the junction of Quamina and Carmichael Streets. He is equally depicted in a mural in the dome at the headquarters of the Guyana Bank for Trade and Industry (GBTI) building in Water Street, Georgetown.

Source:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quamina

http://kofi1763.webs.com/kwamena1823.htm

http://abolition.e2bn.org/resistance_53.html

http://www.guyana.org/features/guyanastory/chapter43.html

1 comment

Very informative and educational in content…