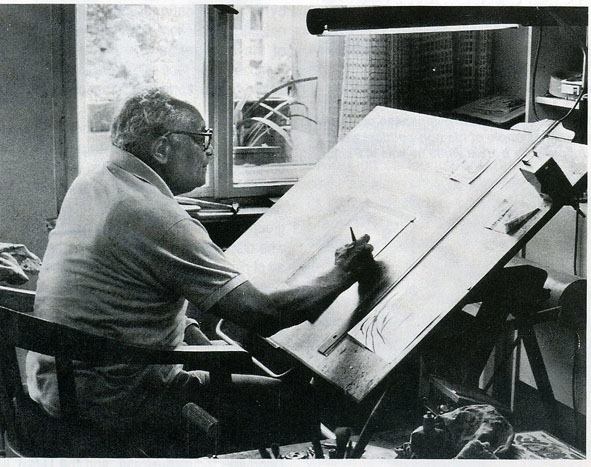

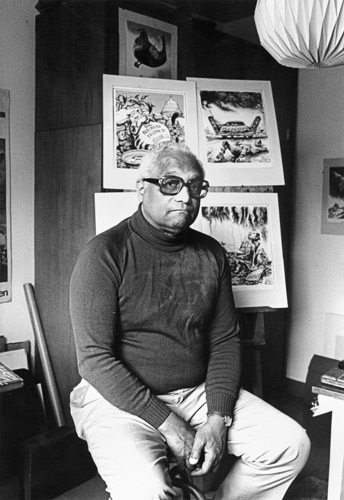

Oliver Wendell Harrington was a political cartoonist and originator of Dark Laughter and Jive Gray comic strips and has been called the “greatest” African American cartoonist.

Harrington was born in Valhalla on 14th February, 1912, the son of an African-American father and a Jewish mother from Budapest. Growing up in the South Bronx, an ethnically diverse neighborhood, Harrington was early on sensitized to racism in American society. After being educated at Yale School of Fine Arts and the National Academy of Design, he contributed cartoons to newspapers in Harlem. One of his main concerns was “to establish a more realistic and less stereotypical depiction of African-American life but also to vent his anger about the continuing racial discrimination in the U.S.”

In the 1932 Presidential Election he used his art to support the campaign of Franklin D. Roosevelt. During the next few years he was a passionate supporter of Roosevelt’s New Deal program.

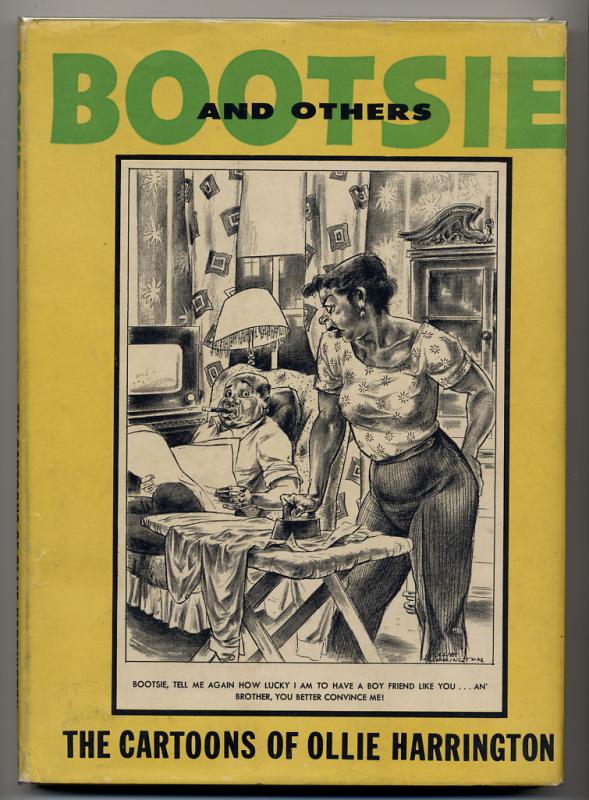

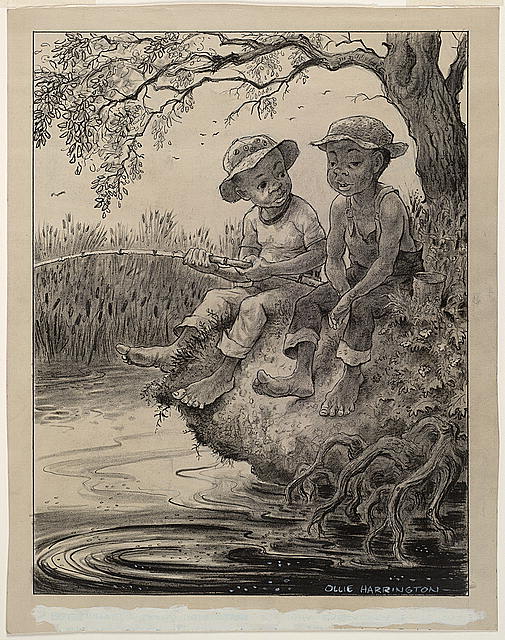

In 1935, Harrington began a satirical and often political cartoon in the Amsterdam News entitled “Dark Laughter” which recorded the absurdities and frustrations of Harlem life. In this context, he developed his best-known cartoon character: Bootsie, an ordinary African-American man coping with everyday racism in American society. Langston Hughes honored his friend’s work when he wrote the introduction for the 1958 anthology Bootsie and Others: A Selection of Cartoons by Ollie Harrington. Hughes also called Harrington “America’s greatest black cartoonist.”

It was the first black comic strip to receive national recognition. Harrington later wrote about the birth of Bootsie: “I simply recorded the almost unbelievable but hilarious chaos around me and came up with a character. I was more surprised than anyone when Brother Bootsie became a Harlem celebrity.” Harrington became the first African American to establish an international reputation in cartooning.

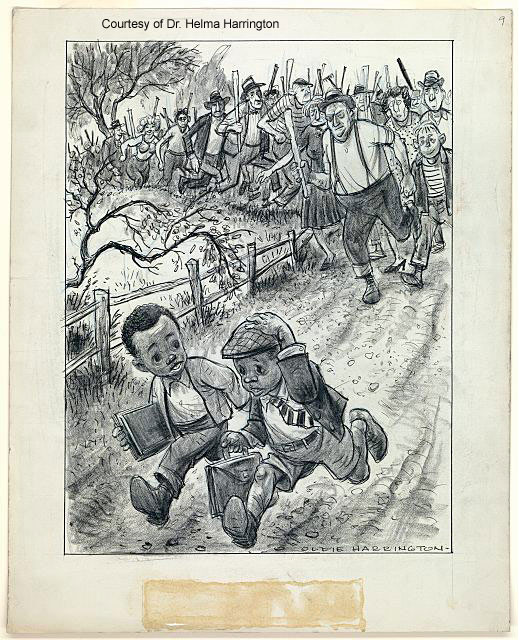

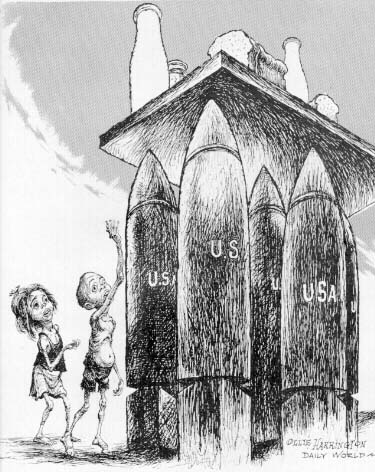

In 1943, the Pittsburgh Courier sent Harrington as a war correspondent to Europe. In Italy, he escorted Walter White, the NAACP executive secretary, to frontlines and documented the situation of African-American soldiers first hand. A common theme of his cartoons at this time was the irony of fighting for rights in Europe that they did not have in their own country. These experiences confirmed Harrington’s notions of World War II as a possible turning point in race relations and also introduced him to a world without a formal color line.

After the war – moved by a wave of brutal lynchings of returning veterans in the South – Harrington accepted White’s proposal to organize the NAACP’s Public Relations Department from which he was able to advocate an end to racial discrimination. In 1946, he explained that he had taken on this struggle because black soldiers had fought “to tear down the sign ‘No Jews Allowed’ in Germany” only to find that “the sign, ‘No Negroes Allowed’” was still there when they returned to their homes. “His political activism on behalf of civil rights brought him to the attention of McCarthy-era witch-hunters. As a result, Harrington left the United States in 1951 and settled in France, where he became part of an active African-American expatriate community, befriending writers such as James Baldwin, Richard Wright, and William Gardner Smith.

During his years abroad, he wrote articles for American periodicals. A collection of those articles, “Why I Left America: And Other Essays,” edited by M. Thomas Inge, was published by University Press of Mississippi in 1993, as was the book “Dark Laughter: The Satiric Art of Oliver W. Harrington,” also edited by Professor Inge, of Randolph-Macon College.

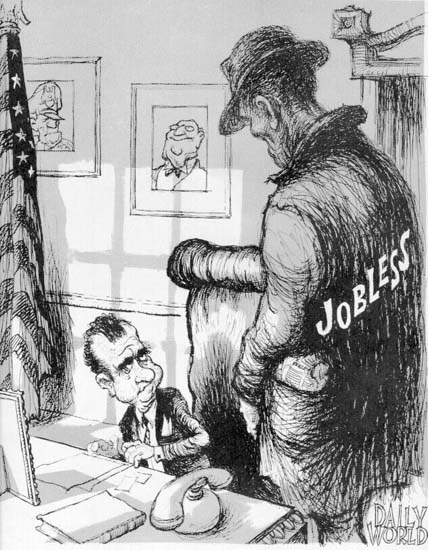

“Dark Laughter” contained some of Mr. Harrington’s best artwork from the six decades beginning with the 1930’s, including much Bootsie cartoon work. It also featured what Mr. Watkins, reviewing both books jointly in The Times, called “the more openly satiric political cartoons” that Mr. Harrington produced for publications in East Germany and elsewhere.

Harrington entered the final phase of his life in 1961 when he left Paris for East Germany. There, he found a lasting marriage to Helma Richter, and an excellent position as journalist and cartoonist for communist state publications. Ironically, Harrington’s life and status on the other side of the Berlin Wall gave him the opportunity to travel extensively in the west, and in 1994, with the McCarthy era long over, he briefly returned to the United States as a visiting journalism professor at Michigan State University. After his death in Germany in 1995, Harrington was honored with the establishment of the Oliver Wendell Harrington Cartoon Art Collection at the Walter O. Evans Collection of African American Art in Savannah, Georgia.

Sources:

http://www.aacvr-germany.org/index.php/images-7/oliver-harrington

http://spartacus-educational.com/ARTharrington.htm

http://www.pbs.org/blackpress/news_bios/harrington.html