“The year 1865 came in, speaking joyful words in our ears… We hail it with joy, because it finds us surrounded with light… This year, this present new year, [the creator] will mount His chariot of power, and will draw his sword of Vengeance…and will drive out the rebels, the slaveholders and the copperheads, and the cry shall be, from the highest mountain to the lowest valley…for slavery is abolished forever.” –N.B. Sterett, Sergeant Major, 39th U.S. Colored Troops.

Juneteeth, a hybrid of the words June and nineteenth, was first recognized and celebrated on June 19, 1865, when Union soldiers sailed into Galveston, Texas, announced the end of the Civil War, and read aloud a general order freeing the approximately 250,000 bondpeople. The celebration, originally limited to the southwestern part of the United States, has been sporadically observed since the 1940s. It is now a Texas state holiday and African-Americans throughout the country commemorates it with parades, concerts, and other cultural observances.

President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863, but this decree was not official or totally enforced until the Confederate surrender at Appomattox, Virginia in April 1865. However, African-Americans remained enslaved in three states: Texas, Delaware, and Kentucky. When the Confederate surrendered in June, the bondpeople in Texas were not notified of the news until June 19. A number of legendary stories attempt to account for the delay in notifying the people of Texas about the end of the Maafa (Atlantic slavery).

One story describes the odyssey of a soldier Lincoln sent traveling by a mule who went to Oklahoma and Arkansas before arriving in Texas, but that story negates accounts of the Union soldiers’ arrival in Galveston Bay. Many people believe that the troops waited until slaveholders had presided over planting the cotton crop before moving to enforce the Emancipation Proclamation in Texas.

Although rooted in Texas the spread of the celebration of Juneteenth in the 1800s parallels migration of African-Americans to the country’s western and northern regions as the people took cultural observations and traditions with them. Early celebrations usually occurred in rural locations not subject to segregation laws, but as the event became popular, Houston’s segregated parks, gradually waived their rules for this special occasion, and eventually, 10 acres of land near Houston was purchased in 1872. In 1898, a community organization was chartered that bought land to establish Booker T. Washington Park in Mexia, located near Waco, to be a permanent location for celebrating the holiday.

Juneteenth’s established customs included ceasing all work activities, wearing elaborate costumes to symbolize the shedding of the Maafa’s rags, digging a barbecue pit as bondpeople used to, and holding a grand picnic with musical entertainment.

Juneteenth celebrations declined during the Great Depression and in the years following the European “World” War. In 1979. Houston representative Al Edwards proposed legislation making June 19 an official Texas state holiday and the bill passed and became law on January 1, 1980. This initiative, combined with a climate for increased cultural pride has helped to resurrect Juneteenth, and it is currently celebrated across the country. Currently, a little more than half of U.S. states acknowledge Juneteenth in some form or another, usually on the third Saturday of June.

Juneteenth is a bittersweet holiday, “a time of celebration, but also a time of reflection, healing, and hopefully a time for the country to come together and deal with its [Maafa] legacy,” says the Rev. Ronald V. Meyers, chairman of the National Juneteenth Observance Foundation.

It must be noted that bondpeople in Delaware and Kentucky had to await the December 1965 ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution before their enslavement ended.

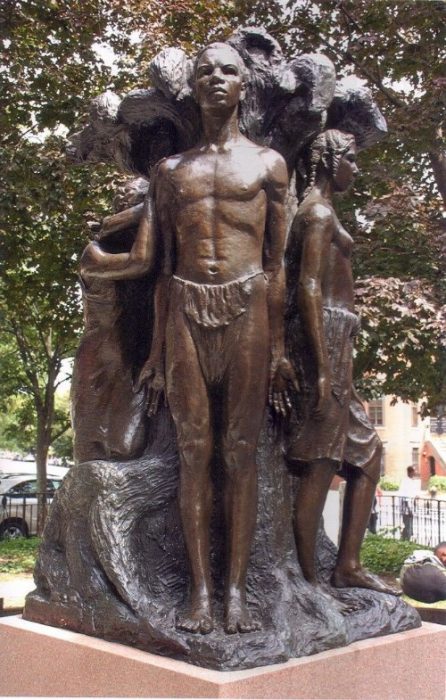

Picture credit:

Retrieved from http://content.time.com/time/nation-article-0,8599,1815936,00.html

Retrieved from https://patch.com/us/across-america/what-juneteenth-5-things-know-holiday

Source:

Juneteenth by Anthony Todman in The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery: Vol 1.

Creating Black Americans by Nell Irvin Painter

There is a River by Vincent Harding