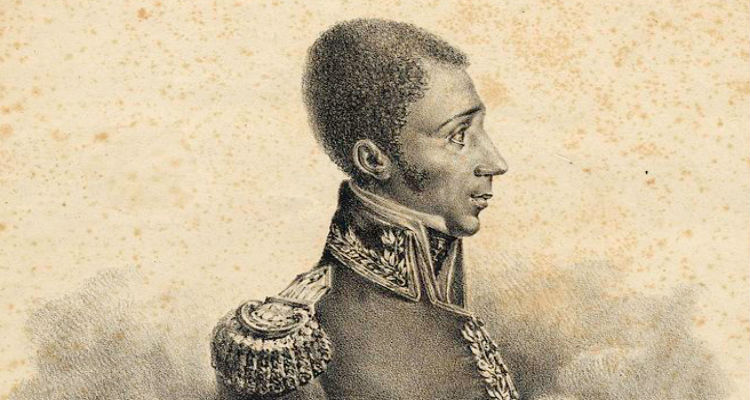

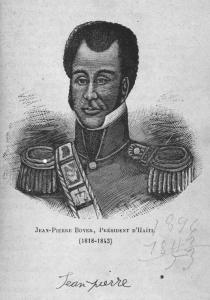

Jean-Pierre Boyer (born 1776—died July 9, 1850) was one of the leaders of the Haitian Revolution and President of Haiti from 1818 to 1843. He reunited the north and south of Haiti in 1820 and also occupied and took control of Santo Domingo, which brought all of Hispaniola under one government by 1822. Boyer managed to rule for the longest period of time of any of the revolutionary leaders of his generation.

Boyer, of mixed African and European descent, was educated in France. He was born in Port-au-Prince as the son of a Frenchman, a tailor by profession, and an African mother, a formerly enslaved woman from Guinea. Heading an urban, wealthy household, his father could afford to send Boyer to France, where he paid for his education at a military school. Boyer joined the French Revolutionary Army and earned the rank of battalion commander. In the early years of the Haitian Revolution, Boyer fought with Toussaint Louverture. He eventually allied himself with André Rigaud, also of mixed ancestry, in the latter’s abortive insurrection against Toussaint to try to keep control of the southern region of Saint-Domingue.

Boyer, of mixed African and European descent, was educated in France. He was born in Port-au-Prince as the son of a Frenchman, a tailor by profession, and an African mother, a formerly enslaved woman from Guinea. Heading an urban, wealthy household, his father could afford to send Boyer to France, where he paid for his education at a military school. Boyer joined the French Revolutionary Army and earned the rank of battalion commander. In the early years of the Haitian Revolution, Boyer fought with Toussaint Louverture. He eventually allied himself with André Rigaud, also of mixed ancestry, in the latter’s abortive insurrection against Toussaint to try to keep control of the southern region of Saint-Domingue.

After going into exile in France, Boyer and Alexandre Pétion, another mixed-race leader, returned in 1802 with the French troops led by General Charles Leclerc.

After it became clear the French were going to try to reimpose slavery and restrictions on free gens de couleur (elite mixed-race), Boyer joined the patriots under Pétion and Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who led the colony to independence.

He served with the Alexandre Sabès Pétion and Henry Christophe after they had killed the Haitian independence leader and self-proclaimed emperor Jean-Jacques Dessalines in 1806. He then served with Pétion against Christophe. After Pétion rose to power in the State of Haiti in the South, he chose Boyer as his successor. Boyer was reportedly under the influence of Pétion lover, Marie-Madeleine Lachenais, who acted as his political adviser. When Pétion and Christophe had died, he succeeded in unifying the country in 1821.

During his presidency, Boyer tried to halt the downward trend of the economy—which had begun with the successful revolt of Blacks against their French enslavers in the 1790s—bypassing the Code Rural. Its provisions sought to tie the peasant laborers to plantation land by denying them the right to leave the land, enter the towns, or start farms or shops of their own and by creating a rural constabulary to enforce the code. These efforts, however, failed to stop the decline in production.

Boyer negotiated an agreement with France in 1825 by which the French consented to recognize Haitian independence in return for the payment of an indemnity of 150 million francs as compensation for the massacre of French plantation owners by Blacks during the Haitian wars of independence. These payments, subsequently reduced to nearly 60 million francs in 1838, along with the destruction of plantation owners’ property, placed an impossible financial burden on the already impoverished Haitian people.

The people of Haiti were distressed at their situation; and the poor economic situation was worsened by an earthquake. The disadvantaged majority rural population rose up under Charles Rivière-Hérard in late January 1843. On 13 February 1843, Boyer fled Haiti to nearby Jamaica. He eventually settled in exile in France, where he died in Paris in 1850. Descendants of Boyer still live in Haiti.

Source:

http://www.britannica.com/biography/Jean-Pierre-Boyer

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Pierre_Boyer