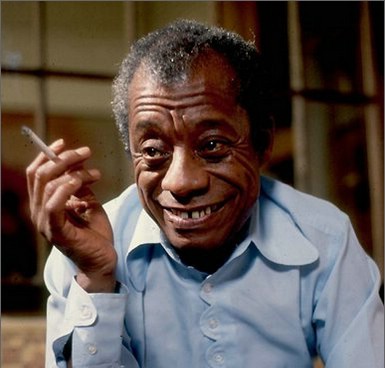

James Arthur Baldwin was an African American novelist, essayist, playwright, poet, and social critic, who is considered to be one of the 20th century’s greatest writers. Born on August 2, 1924, in New York City, James Baldwin published the 1953 novel Go Tell It on the Mountain, going on to garner acclaim for his insights on race, spirituality and humanity. Other novels included Giovanni’s Room, Another Country and Just Above My Head, as well as essay, works like Notes of a Native Son and The Fire Next Time. Having lived in France, he died on December 1, 1987 in Saint-Paul de Vence.

Baldwin was born to a young single mother, Emma Jones, at Harlem Hospital. She reportedly never told him the name of his biological father. Jones married a Baptist minister named David Baldwin when James was about three years old. Growing up in Harlem, the oldest of nine children, James Baldwin cared for his younger siblings in the shadow of an abusive stepfather. His stepfather told him, that he was the ugliest child he had ever seen. Despite their strained relationship, he followed in his stepfather’s footsteps—who he always referred to as his father—serving as a youth minister in a Harlem Pentecostal church from the ages of 14 to 16. Those years and the dawning realization of the difficulties of being black and gay in America are covered in his autobiographical first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, published in 1953.

Baldwin developed a passion for reading at an early age, and demonstrated a gift for writing during his school years. He attended DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, where he worked on the school’s magazine with future famous photographer Richard Avedon. He published numerous poems, short stories and plays in the magazine. After graduating from high school in 1942, he had to put his plans for college on hold to help support his family. He took whatever work he could find, including laying railroad tracks for the U.S. Army in New Jersey. During this time, Baldwin frequently encountered discrimination, being turned away from restaurants, bars and other establishments because he was African-American. After being fired from the New Jersey job, Baldwin sought other work and struggled to make ends meet.

On July 29, 1943, Baldwin lost his father—and gained his eighth sibling the same day. He soon moved to Greenwich Village, a New York City neighborhood popular with artists and writers. Devoting himself to writing a novel, Baldwin took odd jobs to support himself. He befriended writer Richard Wright, and through Wright he was able to land a fellowship in 1945 to cover his expenses. Baldwin started getting essays and short stories published in such national periodicals as The Nation, Partisan Review and Commentary.

Three years later, Baldwin made a dramatic change in his life, and moved to Paris on another fellowship. The shift in location freed Baldwin to write more about his personal and racial background. “Once I found myself on the other side of the ocean, I see where I came from very clearly…I am the grandson of a slave, and I am a writer. I must deal with both,” Baldwin once told The New York Times.

In 1954, Baldwin received a Guggenheim fellowship. He published his next novel, Giovanni’s Room, the following year. The work told the story of an American living in Paris, and broke new ground for its complex depiction of homosexuality, a then-taboo subject. Love between men was explored in a later Baldwin novel Just Above My Head (1978). The author would also use his work to explore interracial relationships, another controversial topic for the times, as seen in the 1962 novel Another Country. Baldwin was very open about his homosexuality and relationships with both men and women.

Baldwin explored writing for the stage a well. He wrote The Amen Corner, which looked at the phenomenon of storefront Pentecostal religion. The play was produced at Howard University in 1955, and later on Broadway in the mid-1960s.

It was his essays, however, that helped establish Baldwin as one of the top writers of the times. Delving into his own life, he provided an unflinching look at the black experience in America through such works as Notes of a Native Son (1955) and Nobody Knows My Name: More Notes of a Native Son (1961). Nobody Knows My Name hit the bestsellers list, selling more than a million copies, and propelled Baldwin into being one of the leading voices in the Civil Rights Movement.

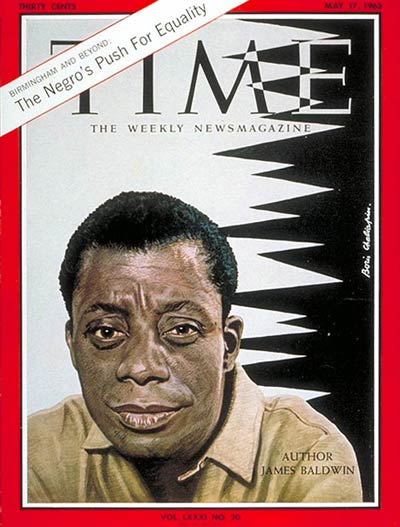

In 1963, there was a noted change in Baldwin’s work with The Fire Next Time. This collection of essays was meant to educate whyte Americans on what it meant to be black. In the work, Baldwin offered a brutally realistic picture of race relations, but he remained hopeful about possible improvements. “If we…do not falter in our duty now, we may be able…to end the racial nightmare.” His words struck a cord with the American people, and The Fire Next Time sold more than a million copies.

That same year, Baldwin was featured on the cover of Time magazine. “There is not another writer—[whyte] or black—who expresses with such poignancy and abrasiveness the dark realities of the racial ferment in North and South,” Time said in the feature.

Baldwin wrote another play, Blues for Mister Charlie, which debuted on Broadway in 1964. The drama was loosely based on the 1955 racially motivated murder of a young African-American boy named Emmett Till. This same year, his book with friend Richard Avalon, entitled Nothing Personal, hit bookstore shelves. The work was a tribute to slain Civil Rights leader Medgar Evers. Baldwin also published a collection of short stories, Going to Meet the Man, around this time.

In his 1968 novel Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone, Baldwin returned to popular themes—sexuality, family and the black experience. Some critics panned the novel, calling it a polemic rather than a novel. He was also criticized for using the first-person singular, the “I,” for the book’s narration.

By the early 1970s, Baldwin seemed to despair over the racial situation. He witnessed so much violence in the previous decade—especially the assassinations of Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.—because of racial hatred. This disillusionment became apparent in his work, which employed a more strident tone than in earlier works. Many critics point to No Name in the Street, a 1972 collection of essays, as the beginning of the change in Baldwin’s work. He also worked on a screenplay around this time, trying to adapt The Autobiography of Malcolm X by Alex Haley for the big screen.

While his literary fame faded somewhat in his later years, Baldwin continued to produce new works in a variety of forms. He published a collection of poems, Jimmy’s Blues: Selected Poems, in 1983 as well as the 1987 novel Harlem Quartet. Baldwin also remained an astute observer of race and American culture. In 1985, he wrote The Evidence of Things Not Seen about the Atlanta child murders. Baldwin also spent years sharing his experiences and views as a college professor. In the years before his death, he taught at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and Hampshire College.

Baldwin died on December 1, 1987, at his home in St. Paul de Vence, France. Never wanting to be a spokesperson or a leader, Baldwin saw his personal mission as bearing “witness to the truth.” He accomplished this mission through his extensive, rapturous literary legacy.

Source:

http://www.biography.com/people/james-baldwin-9196635#legacy

http://bandofthebes.typepad.com/bandofthebes/2012/08/page/2/