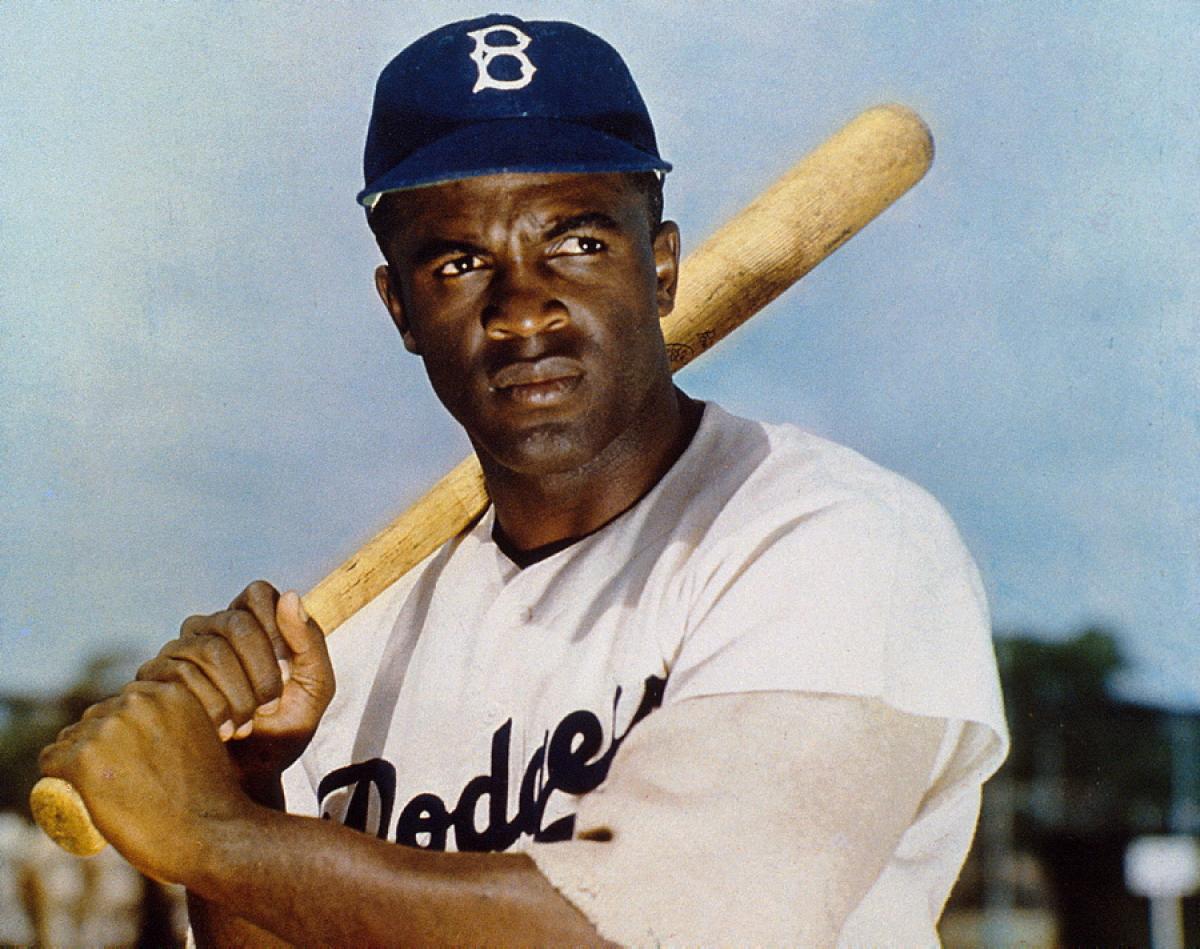

Jackie Robinson made history in 1947 when he broke baseball’s color barrier to play for the Brooklyn Dodgers. A talented player, Robinson won the National League Rookie of the Year award his first season, and helped the Dodgers to the National League championship – the first of his six trips to the World Series. In 1949 Robinson won the league MVP award, and he was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962. Despite his skill, Robinson faced a barrage of insults and threats because of his race.

Jack Roosevelt Robinson, the youngest of five children, was born in Cairo, Georgia on January 31, 1919 to sharecroppers Jerry and Mallie Robinson. When Jack was a year old his father deserted the family, and Mallie Robinson relocated her family to Pasadena, California where Jack grew up. Robinson’s athletic ability was apparent from an early age. In high school he participated in five sports: basketball, football, baseball, tennis and track. He continued to play multiple sports at Pasadena Junior College, where he graduated in 1939, and then at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles (UCLA). While at UCLA, Robinson became the first athlete to earn varsity letters in four sports. Despite his athletic accomplishments, Robinson believed that his chances of playing on any major league sports team after graduation were slim, given the racism of the era, and in 1941 he left college just shy of graduation to take a job as an assistant athletic director with the National Youth Administration in Atascadero, California. The position, however, was short-lived as government funding for the job ended the following year.

Robinson eventually decided to enlist in the U.S. Army. After two years in the army, he had progressed to second lieutenant. Jackie’s army career was cut short when he was court-martialed in relation to his objections with incidents of racial discrimination. In the end, Jackie left the Army with an honorable discharge.

In 1945, Jackie played one season in the Negro Baseball League, traveling all over the Midwest with the Kansas City Monarchs. But greater challenges and achievements were in store for him. In 1947, Brooklyn Dodgers president Branch Rickey approached Jackie about joining the Brooklyn Dodgers. The Major Leagues had not had an African-American player since 1889, when baseball became segregated. Robinson spent the 1946 season with the Dodger’s farm team, the Montreal Royals. Also that year he married his college sweetheart, Rachel Isum. The couple had three children, Jackie Jr. (1946), Sharon (1950), and David (1952).

When Jackie first donned a Brooklyn Dodger uniform, he pioneered the integration of professional athletics in America. By breaking the color barrier in baseball, the nation’s preeminent sport, he courageously challenged the deeply rooted custom of racial segregation in both the North and the South.

General Manager Branch Rickey’s offer to break the color line also came with a condition: that he not respond to the abuse he would face.

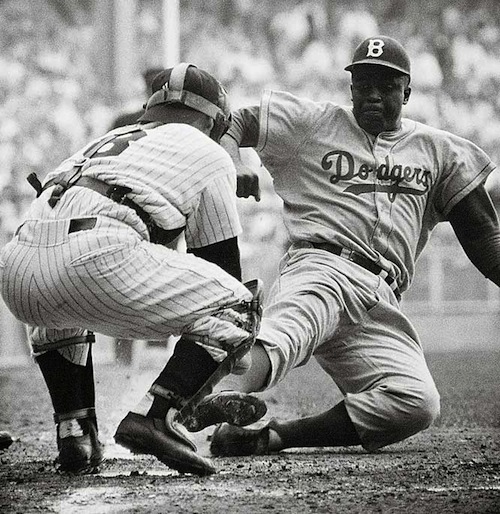

Jackie Robinson’s debut in organized baseball is a legend (April 18, 1946, with the Montreal Royals of the International League, the Dodgers’ best farm club). In five at-bats he hit a three-run homer and three singles, stole two bases, and scored four times, twice by forcing the pitcher to balk. Promoted to the Dodgers the following spring, Robinson thrived on the pressure and established himself as the most exciting player in baseball. His playing style combined traditional elements of black sports–the opportunistic risk taking known as “tricky baseball” in the Negro Leagues–with an aggressiveness asserting his right to be at the plate or on the basepaths. According to his manager Leo Durocher, “This guy didn’t just come to play. He come to beat ya.”

During his first two years with the Dodgers, Robinson kept his word to Rickey and endured astonishing abuse amid national scrutiny without fighting back. His dignified courage in the face of virulent racism–from jeers and insults to beanballs, hate mail, and death threats–commanded the admiration of whites as well as blacks and foreshadowed the tactics that the 1960s civil rights movement would develop into the theory and practice of nonviolence.

Robinson, however, finally broke his emotional and political silence in 1949, becoming an outspoken and controversial opponent of racial discrimination. He criticized the slow pace of baseball integration and objected to the Jim Crow practices in the southern states where most clubs conducted spring training. Robinson led other ballplayers in urging baseball to use its economic power to desegregate southern towns, hotels, and ballparks.

In ten seasons with the Dodgers, Robinson played in six World Series games including the Dodgers’ 1955 World Championship. He played in six consecutive All-Star Games, from 1949 to 1954, and retired at the end of the 1956 season. In 1962, his first year of eligibility, Robinson was inducted in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. In retirement, Robinson was an active participant in the struggle for civil rights, working with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). He also wrote for The New York Post and The Amsterdam News. Jackie Robinson died of a heart attack on October 24, 1972 at his home in Stamford, Connecticut. He was 53. On March 26, 1984, Robinson was posthumously awarded the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Medal of Freedom, by President Ronald Reagan. In 1996 the U.S. Congress and President Clinton authorized a coin to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of Robinson’s 1947 entry into major league baseball. In 1997 the U.S. Post Office issued a stamp in his honor, and on the 50th anniversary of the date that Robinson broke major league baseball’s color barrier, Major League Baseball retired Robinson’s number 42.

Sources:

http://jackierobinson.com/about/bio.html

http://www.blackpast.org/aaw/robinson-jack-jackie-roosevelt-1919-1972#sthash.z1e6j8Oj.dpuf

http://www.history.com/topics/black-history/jackie-robinson