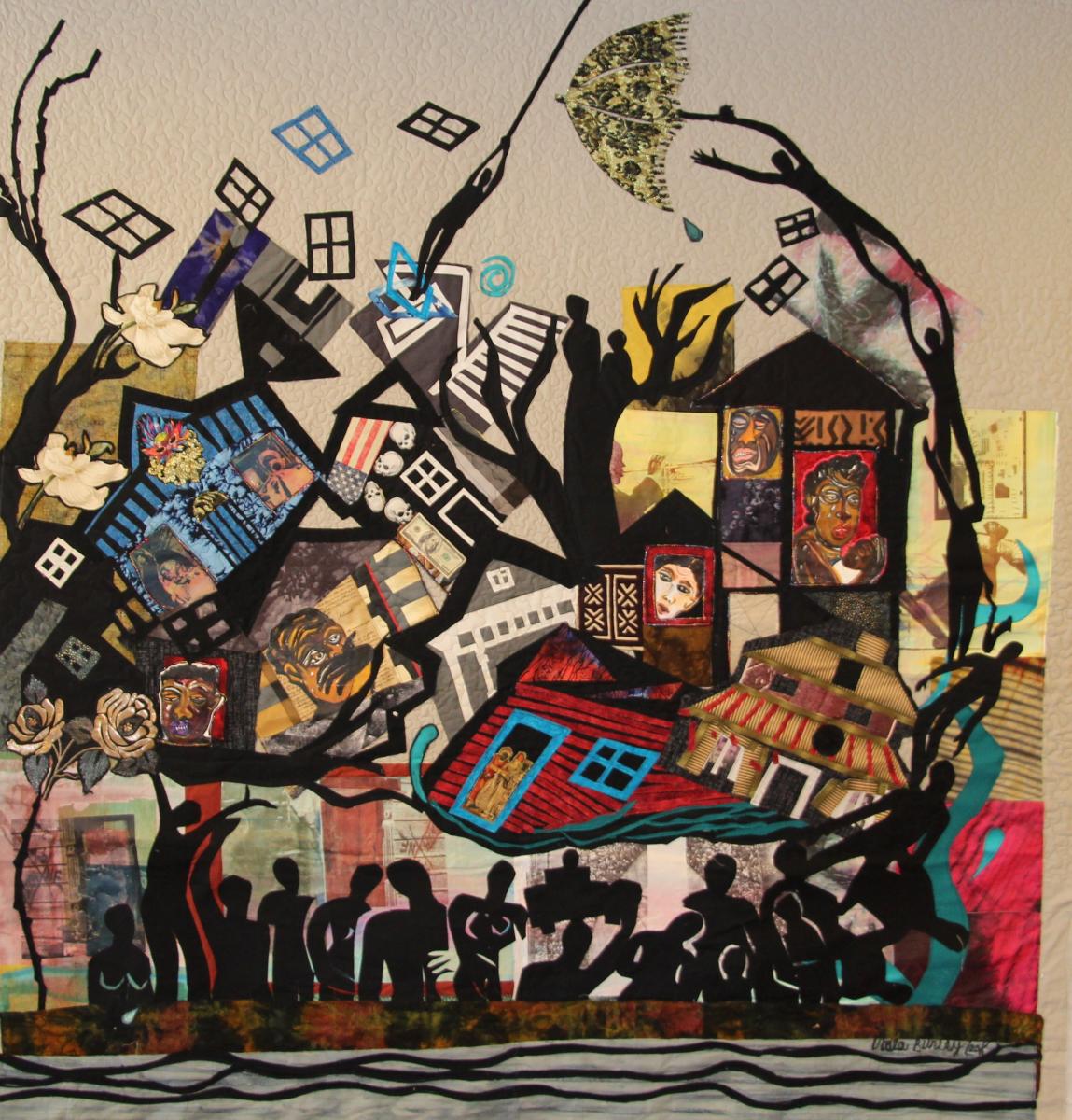

[dropcap size=small]H[/dropcap]urricane Katrina which formed over the Bahamas on August 23, 2005, was the deadliest and most destructive Atlantic tropical cyclones of the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season. It was also the most catastrophic natural disaster in the history of the United States. Katrina is the seventh most intense Atlantic hurricane ever recorded, part of the 2005 season that included three of the six most intense Atlantic hurricanes ever documented (along with #1 Wilma and #4 Rita). Katrina caused at least 1,833 death, with more than one million people displaced and damages estimated at $108 billions.

From the Caribbean waters, Katrina moved west and neared the Florida coast on the evening of 25 August. After crossing southern Florida – where it left some 100,000 homes without power – it strengthened further before veering inland towards Louisiana, eventually making landfall at Grand Isle, approximately 90km south of New Orleans, at 10am local time on 29 August. At this point, Katrina’s sustained wind speed was approximately 200 km/h. The storm then passed directly through New Orleans. The hurricane caused severe destruction across the entire Mississippi coast and into Alabama, as far as 100 miles (160 km) from the storm’s center.

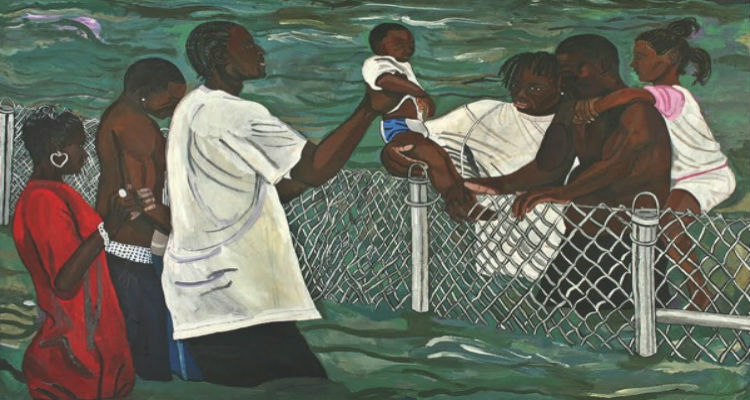

New Orleans, the city with the highest percentage of native-born residents of any U.S. city, and “…the only exotic place in America,” was almost destroyed by Katrina after drainage canals were breached. Over 80% of New Orleans was flooded after 53 different levees designed to protect the city failed, with some parts under 15 feet (4.6 m) of water. Although between 80 and 90 percent of the residents were evacuated safely in time before the hurricane struck, those who lacked the means or ability to evacuate were left stranded in the city.

The famous French Quarter dodged the massive flooding. The hardest hit, the place where so many lost their lives was the Lower Ninth Ward, a neighborhood of mostly poor black families. At the time, it was the home of about 14,000 people. Now fewer than 3,000 people live there — a decade after most of the homes were simply washed away.

The images of New Orleans with desperate citizens wading through the deluge, people trapped on roof-tops for days, decomposing bodies left on city streets, thousands left without food and water inside the superdome, and neighourhoods flooded with toxic water and sewage shocked the world, with Fema (Federal Emergency Management Agency), the state of Louisiana and the US government coming under heavy criticism for their delayed response to the humanitarian crisis. “Katrina represented one of the biggest government response failures in modern history.”

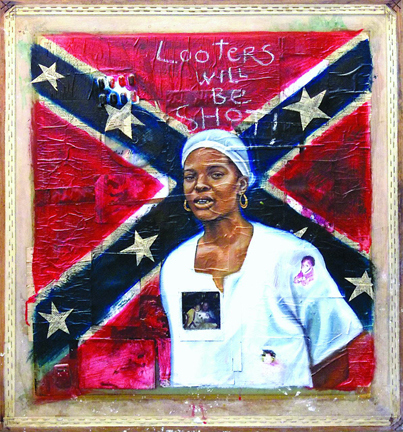

In addition, hundreds of mercenaries descended on New Orleans to guard the property of the city’s millionaires. New Orleans was turned into an armed camp, patrolled by heavily armed men, employed by private military companies including Blackwater and ISI. The Blackwater operators described their mission in New Orleans as “securing neighborhoods.” When National Guard troops descended on the city, they described their role as fighting “the insurgency in the city.” Brigadier Gen. Gary Jones, who commanded the Louisiana National Guard’s Joint Task Force, said, “This place is going to look like Little Somalia. We’re going to go out and take this city back. This will be a combat operation to get this city under control.”

The local police superintendent ordered all weapons, including legally registered firearms, confiscated from civilians. But, that order didn’t “apply to hundreds of security guards hired by businesses and some wealthy individuals to protect property…[who] openly carry M-16’s and other assault rifles.”

Neither did the order include a racist armed whyte vigilante group called the Algiers Point Militia that also started patrolling the streets using deadly force against African-Americans when they deem it necessary. At least 11 African-Americans were shot dead. Whyte vigilantes say they shot Black men on sight for being in the neighborhood during Katrina. One of the whyte vigilantes even bragged on video about going hunting for Black people.

“It was great! Like pheasant season in South Dakota. If it moved, we shot it.”

Malik Rahim, an African-American community activist, was one of the organizers of the Common Ground Collective, which quickly began dispensing basic aid and medical care in the first days after the hurricane. He stated that instead of aiding the relief workers, the police and troops who were patrolling the streets treated them as criminals or “insurgents.” Common Ground had to rely on whyte volunteers to move through the city because it had simply become too perilous for Blacks.

While the government couldn’t seem to keep people from dying on rooftops or abandoned highways, it wasted no time building a temporary jail in New Orleans. The warden of the notorious Angola Prison, a former slave plantation that’s now home to 5,000 inmates, was rushed down to the city to oversee “Camp Greyhound” in the city’s bus terminal. According to the New Orleans Times-Picayune, the jail “was constructed by inmates from Angola and Dixon state prisons and was outfitted with everything a stranded law enforcer could want, including top-of-the-line recreational vehicles to live in and electrical power, courtesy of a yellow Amtrak locomotive.

In the end, reports of residents firing at National Guard helicopters, of tourists being robbed and raped on Bourbon Street, and of murderous rampages in the Superdome—all turned out to be false.

Weeks later, many of African American citizens of the Lower Ninth Ward attempted to return to rebuild their lives. But it wasn’t so simple. In October 2005, National Guard troops blocked more than 10,000 people from visiting their property. Three years later, tens of thousands of people were still living in trailers issued by FEMA that were found to contain high levels of toxic formaldehyde.

Ten years later, four of the city’s poorest neighborhoods, including the Lower Ninth Ward, are still largely abandoned, with less than half of their pre-storm populations. Racial inequality remains. The employment rate for black men was 57% in 2013, the Data Center found in a study. According to the report: “The median income for whyte households in metro New Orleans is on par with whyte households nationwide, but the median income for black households in metro New Orleans is 20% lower than black households nationally.”

Source:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Effects_of_Hurricane_Katrina_in_New_Orleans

http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/hurricane-katrina-10th-anniversary-archive-footage-devastation-new-orleans-1516442

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jfSAqNnP7kk

http://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/hurricane-katrina-10-yrs-new-orleans-struggles-article-1.2334479

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/vivian-norris-de-montaigu/9-years-after-hurricane-katrina_b_5739262.html

http://blog.nola.com/notesonneworleans/2008/12/white_new_orleanian_brags_abou.html