Harry Jerome was one of the fastest men in the world for nearly a decade. He equaled and set numerous Canadian sprint records, as well as several world records. He participated in three Olympic Summer Games (1960, 1964, and 1968), winning a bronze medal in the 100 meter sprint in 1964. Later, he made important contributions to the development and promotion of amateur sport and fitness in Canada. His many honours include receiving the Order of Canada, and induction into the Canada and BC Sports Halls of Fame, Canadian Athletic Hall of Fame, and Canada’s Walk of Fame.

Jerome was the first man to share world 100-yard and 100 m records. While attending the University of Oregon on an athletic scholarship in 1960, Jerome ran the 100 m in 10.0 sec, tying German Armin Hary’s world record; in 1962 he ran the 100 yards in 9.2 sec, equaling the mark of Frank Budd and Bob Hayes.

Jerome was born September 30, 1940 in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan. He broke the 31-year-old Canadian record for the 220-yard sprint at age 18 – held by 1928 double Olympic gold medalist Percy Williams. A year later he emerged as an international sensation by equaling the world record for 100 meters by clocking 10.0 seconds at the Canadian Olympic Trials in Saskatoon. That effort marked the young Canadian as one of the sprinters to watch at the upcoming 1960 Summer Olympic Games in Rome.

But what should have been a promising Olympic debut for Jerome became instead the first of many difficult trials that served as a test of the athlete’s personal motto: Never Give Up. Jerome pulled a muscle in the 100-metre semi-finals in Rome and was out of the competition. Two years later, at the 1962 British Empire and Commonwealth Games in Perth, Australia, world record holder Jerome pulled up lame and finished last in the 100-yard final. The media lambasted him as “a quitter” even as tests confirmed he had suffered severely torn left thigh muscles that would keep him out of competition for all of 1963, with a possible prognosis of never again being able to compete.

He returned, however, in 1964 and was finally able to reap the benefit of his work, tenacity and considerable talent. At the Summer Olympics in Tokyo Jerome earned a bronze medal in the 100-metre final, rightfully earning his spot on the Olympic podium and a respected place among the ranks of the world’s fastest men. Two days later he finished fourth in the 200 meters, confirming his place among the great sprinters of his day while finally earning some grudging respect from Canadian media that seemed to relish in judging him harshly.

Two years later Jerome won the 100 yards final at the 1966 British Commonwealth Games in Jamaica, his first gold medal at a major international Games. That year he also set a world record of 9.1 seconds over 100 yards. In 1967 he also took gold at the Pan-American Games.

In 1968 he represented Canada at his third Olympic Games – an extraordinary feat in itself given that longevity in the sport was not what doctors were predicting when he suffered his first major injury back in 1960. He finished seventh in the Olympic final at Mexico City, confirming that despite the array of physical troubles and negative press that had plagued him over the years, he never gave up.

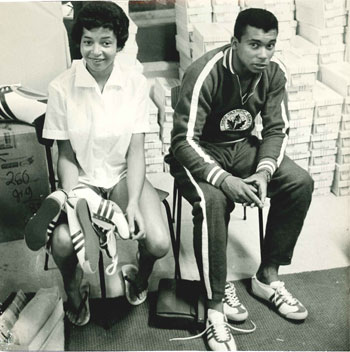

Despite his athletic successes, Harry was always conscious of the challenges facing African Canadians. At the University of Oregon, he coupled his athletic achievements with scholastic success, earning both undergraduate and graduate degrees in science. He would also turn his athletic accomplishments into opportunities for others. Using his celebrity and sports contacts, Harry would obtain equipment for young athletes who could not afford the expensive gear. He was also involved in extensive work to create opportunities for Blacks outside the sports arena. He was a vocal opponent of the misrepresentation of African Canadians in Canadian television, asking that licenses be suspended “if stations could justify neither having Blacks as on-air personalities nor airing stories about the [African Canadian] community.”

He was equally concerned about the opportunity for economic development among African Canadians. He fought to remove wage discrimination barriers against Blacks, and strove to improve mainstream Canadians’ perception of the Black community. Once he wrote to the major department stores questioning the lack of Blacks as models in their catalogues and as clerks in their stores. Despite his stature in the greater community, Harry never forgot about his roots or his role in bringing about positive change.

After retirement, Jerome taught, consulted for Sport Canada and travelled Canada inspiring youngsters to try track and field sports. In 1982, Harry Jerome died suddenly at the age of 42. Despite his passing, he left a considerable legacy that is a source of pride for all Canadians. In 1988, a statue in his honour was erected along the sea wall of Vancouver’s Stanley Park. Both the University of Oregon and the province of British Columbia have recreational facilities that bear his name.

Sources:

http://www.harryjerome.com/history/harry-jerome/

http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/harry-jerome/

http://bbpa.org/events-programs/harry-jerome-awards/about-harry-jerome/

Harry Winston Jerome: Person of National Historical Significance