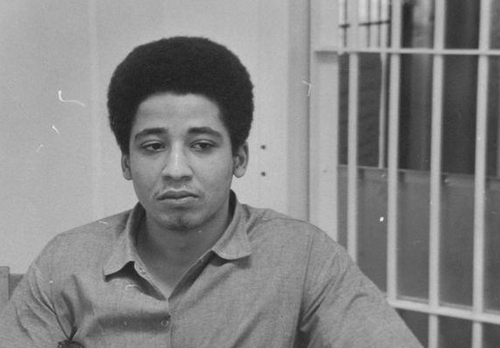

George Lester Jackson was an African-American political revolutionary, prisoners’ rights activist, author, a member of the Black Panther Party, and co-founder of the Black Guerrilla Family while incarcerated. His life story is a constant reminder of how the human spirit takes its stand even while being physically locked down. A revolutionist in the making, Jackson made efforts to eradicate racism and provide safety and dignity to prison inmates.

Jackson was born on September 23, 1941, on Chicago’s West Side, the second of five children. His father, Lester, was a postal worker. Georgia Jackson, George’s mother, was overprotective, rarely allowing her son to leave the house. Growing up in a segregated neighborhood, Jackson did not see a white person until he started kindergarten. He was so curious about the strange-looking children in his class that he approached the first white boy he saw and started feeling his straight hair and scratching the pale skin on his cheek. The boy responded by knocking Jackson out with a baseball bat.

After that event, Mrs. Jackson transferred her son into a parochial school, St. Malachy. He soon discovered that St. Malachy was actually two separate schools across the street from each other—a run down one for black kids and a well-equipped one for white kids. During the summers, Jackson was sent downstate to stay with his grandmother and aunt in his mother’s hometown of Harrisburg, Illinois, in order to get him away from the dangers of urban life. Jackson enjoyed the relative freedom he was given in the country, and he especially liked learning to use guns and rifles.

Meanwhile, the Jackson family began to outgrow its Chicago apartment. After two more children were born, they moved into a new apartment that was larger, but located in a more dangerous neighborhood. Jackson began sneaking out of the house more and more, and his life on the street included petty crimes of all sorts. By about 1950, he was having run-ins with the law on a regular basis. The family soon moved again, this time into the Troop Street housing projects. The projects served as a virtual training ground for criminal behavior. By the time he was a teenager, the quick-learning and increasingly rebellious Jackson had graduated from shoplifting to mugging and other more serious offenses. He would often disappear from home for days at a time.

In an effort to straighten his son up, Lester Jackson obtained a transfer from the post office and moved George across country to Los Angeles in 1956. The move did nothing to alter the young Jackson’s behavior. He quickly became involved in a street gang called the Capones. Jackson’s first California arrest came in January of 1957, when he was taken in for stealing a motorcycle. Several more arrests followed in quick succession, but as a minor he was always released into his father’s custody. Eventually, a department store break-in finally landed him in the Paso Robles youth facility north of Los Angeles. Although he missed the freedom to roam, Jackson’s stay at Paso Robles was not all that bad. He liked the food and, more importantly, he enjoyed the opportunity to read a lot.

Released from the youth camp after seven months, Jackson returned to Los Angeles, where he quickly resumed his career as a robber. He pleaded guilty to a Bakersfield gas station hold-up, then calmly walked out of the county jail by tying up and impersonating another inmate who was scheduled to be released. He was eventually recaptured in Harrisburg, Illinois, where he had spent summers as a boy. He was brought back to California and returned to a California Youth Authority facility, where he remained until his parole in June of 1960.

At 16, he was accused of stealing $71 from a gas station for which he received an indeterminate sentence of one year to life in which his case was reviewed annually. Jackson was never granted parole and spent the rest of his life in prison.

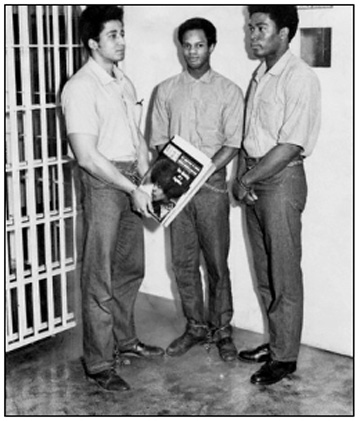

While incarcerated at Soledad Prison in Salinas, CA., he became politicized and began studying the theories of Mao Zedong, Frantz Fanon, and Fidel Castro. He developed strong ideas viewing capitalism as the source of the oppression of people of color, and became the leader in the politicization of Black and Chicano prisoners in Soledad. On January 16, 1970, in response to the death of three Black Muslims, a white guard (John Mills) was killed; Jackson, Fleeta Drumgo, and John Clutchette were accused of the murder. The three became known as the “Soledad Brothers.”

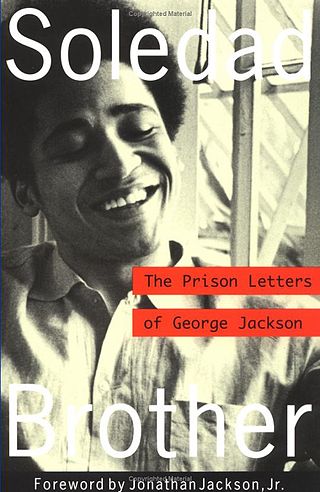

The fate of the Soledad Brothers became an international cause célèbre, which focused on the treatment of blacks in prison. The publication of Jackson’s book “Soledad Brother” that same year added to his visibility. For many supporters, the issue was the belief that the Soledad Brothers were victims of a prison conspiracy. In August 1970, Jackson’s teenage brother Jonathan was killed in the Marin County Courthouse in an attempt to rescue his brother.

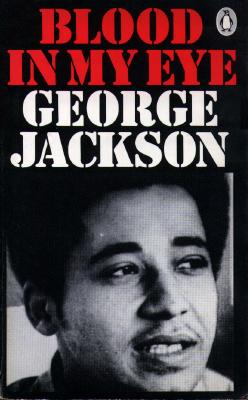

The judge and two of the inmates were also killed during the episode. In the summer of 1971, Jackson was sent back to San Quentin to await trial for his alleged role in the killing of the Soledad guard. While there, he completed another book of essays and letters, Blood in My Eye. In this second book, Jackson predicted and called for civil war in the United States. He also predicted his own murder in prison.

A week after the completion of Blood in My Eye, one of those predictions may have come true. On August 21, 1971, Jackson was shot while allegedly trying to escape from San Quentin. There is still widespread disagreement about what actually took place that day. According to prison officials, Jackson’s lawyer Stephen Bingham smuggled in a gun, which Jackson then concealed under an Afro wig. Jackson then shot a guard, released several other prisoners, and made a break for the prison wall, before being gunned down by tower guards. Three guards and two other prisoners were also killed during the chaos. Supporters of Jackson point to a number of inconsistencies and improbable elements in that story. They believe that Jackson was set up and murdered by prison authorities because he had become too powerful and posed a serious threat to their control. Meanwhile, Bingham disappeared from sight and remained a fugitive until the mid-1980s, when he was tried for and acquitted of smuggling the gun to Jackson.

Tributes to Jackson included memorial services, work stoppages, and silent protests around the country. The most dramatic response to Jackson’s death occurred at Attica Correctional Facility in western New York, where a series of prisoner actions culminated in twelve hundred inmates seizing control of the facility in September 1971. People incarcerated in California prisons honored Jackson each year by wearing black armbands during the month of August. This remembrance grew into the “Black August” movement, an annual opportunity to study and reflect on African-American history, radical political traditions, and contemporary social conditions.

George Jackson’s writings, activism, and martyrdom honed and popularized the idea that incarceration served to control African Americans in ways that supported racism and imperialism. He also insisted that prisoners–as leaders of a revolutionary movement–held the power to change these conditions.

Sources:

http://www.aaregistry.org/historic_events/view/george-jackson-soledad-brother

http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/George_Jackson.aspx

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Jackson_(Black_Panther)

http://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/george-lester-jackson-1494.php

http://www.anb.org/articles/15/15-01374.html