David Walker was an outspoken African-American abolitionist and anti-Maafa (Atlantic slavery) activist. In 1829, while living in Boston, Massachusetts, he published An Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World, a call for Black unity and self-help in the fight against oppression and injustice.

Walker was born on September 28, 1785, in Wilmington, North Carolina to a free mother and an enslaved father who died before his birth. Walker grew up to despise the system of the Maafa (Atlantic slavery) that the U.S. government allowed in America. He knew the cruelties of the Maafa were not for him and said, “As true as God reigns, I will be avenged for the sorrow which my people have suffered.” He eventually moved to Boston during the 1820s and became very active within the free black community. Walker’s intense hatred for the Maafa culminated in him publishing his Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World in September 1829. The Appeal was smuggled into the southern states, and was considered subversive, seditious, and incendiary by most whyte men in both northern and southern states. It was, without a doubt, one of the most controversial documents published in the antebellum period.

The circulation of the Appeal in the South by the summer of 1830 caused great alarm, particularly in Georgia, Virginia, and North Carolina. It made its first appearance in Walker’s home state in Wilmington, where copies were smuggled on ships from Boston or New York and were distributed by an enslaved person thought to have been an agent of Walker’s. Excitement among whytes soon spread to Fayetteville, New Bern, Elizabeth City, and other towns in the state, particularly where news of the pamphlet was accompanied by rumors of enslaved person insurrection plots scheduled to take place at Christmas. Many communities petitioned Governor John Owen for protection as the enslaved became “almost uncontrollable.” The governor sent a copy of the Appeal to the legislature when it met in November 1830 and urged that it consider measures to avert the dangerous consequences that were predicted. Meeting in secret session, the legislature enacted the most repressive measures ever passed in North Carolina to control enslaved and free blacks. Harsh penalties were to be levied on anyone for teaching enslaved persons to read or write and for circulating seditious publications. Manumission laws were made more prohibitive, and the movements of both enslaved and free blacks were severely restricted. (The fact that Walker was a free black man aroused particular suspicion of those of similar status in the state.) Finally, a quarantine law called for any black entering the state by ship to be confined, and any contact between resident blacks and incoming ships was prohibited.

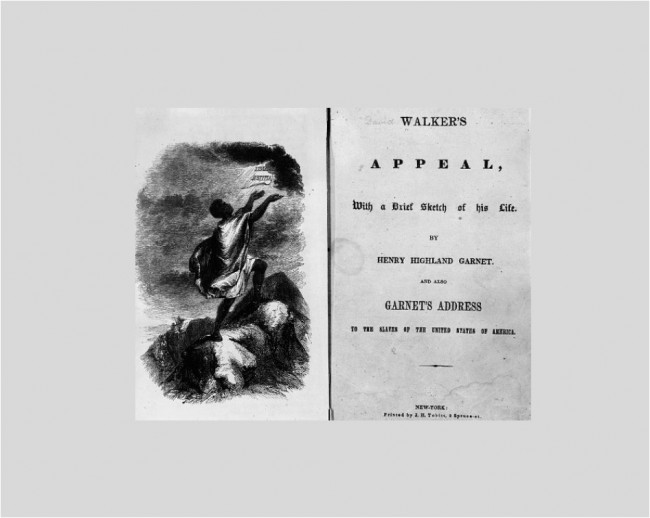

The impact of Walker’s Appeal in North Carolina and elsewhere in the South has been overshadowed by the Nat Turner Rebellion just across the North Carolina border in South Hampton County, Virginia, in August 1831. The two events together led to a major turning point in antebellum race relations throughout the South. Because of the violent and extreme measures it advocated, the Appeal failed to win the support of most Abolitionists or free blacks. But in 1848 it found a new and wider audience when it was reprinted, along with a biographical sketch of Walker, by Henry Highland Garnet, a prominent black minister, newspaper editor, and Abolitionist in New York City.

Walker was concerned about many social issues affecting free and enslaved Africans in America during the time. He also expressed many beliefs that would become commonly promoted by later Black nationalists such as: the unified struggle for resistance to oppression (the Maafa); land reparations; self-government for people of African descent in America; racial pride; and a critique of American capitalism.

Walker died June 28, 1930, in Boston three months after the publication of his pamphlet’s third edition. The cause of his death remains a mystery, though it was widely believed that he was poisoned, possibly as a result of large rewards offered by Southern slaveholders for his death. His only child, Edward G. Walker, was born after his death and in 1866 became the first black elected to the Massachusetts state legislature.

Sources:

http://www.blackpast.org-aah/walker-david-1785

http://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/walker/bio.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Walker_(abolitionist)