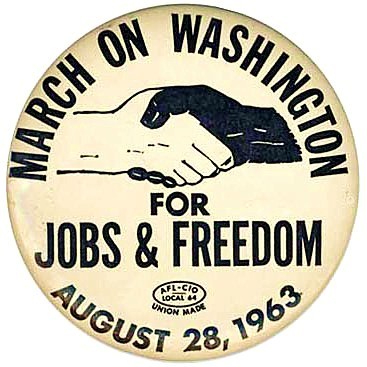

[dropcap size=small]O[/dropcap]n August 28, 1963, more than 250,000 demonstrators took part in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in Washington D.C. The march was successful in pressuring the administration of John F. Kennedy to initiate a strong federal civil rights bill in Congress. During this event, Martin Luther King delivered his memorable ‘‘I Have a Dream’’ speech.

Throughout 1962, civil rights activists had been discussing the need for a large national demonstration to push for federal legislation to combat discrimination. After the widely publicized protests in segregated Birmingham, Alabama, President John F. Kennedy went on record for the first time condemning racial injustice, and it seemed to be the perfect climate for a mass march. A. Philip Randolph, president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, proposed a mass march on Washington, D.C., modeled after his 1941 March on Washington Movement.

There were many competing ideas for the march. Randolph and the Negro American Labor Council (NALC) wanted to highlight the disproportionate poverty of black America, while the more militant wing of the movement, led by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), were disappointed at what they saw as President Kennedy’s lackluster support for the civil rights work they had been doing for years in the South and saw this as an opportunity to pressure the administration.

Kennedy himself feared that mass demonstration would hurt the chances of passage of a civil rights bill, and put pressure on National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) executive secretary Roy Wilkins and National Urban League chief Whitney Young to limit the march’s objectives to support for the civil rights bills in Congress and nothing more. In the months leading up to the march, Kennedy, Wilkins, and Young did everything they could to ensure that the speeches made at the march would be temperate in tone and moderate in their calls. In the push to make the march “respectable” rather than offensive to the administration and much of white America, the original economic focus of the march was lost. A draft of John Lewis’ prepared speech, circulated before the march, was denounced by Reuther, Burke Marshall, and Patrick O’Boyle, the Catholic Archbishop of Washington, D.C., for its militant tone. In the speech’s original version Lewis charged that the Kennedy administration’s proposed Civil Rights Act was ‘‘too little and too late,’’ and threatened not only to march in Washington but to ‘‘march through the South, through the heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did. We will pursue our own ‘scorched earth’ policy’’. In a caucus that included King, Randolph, and SNCC’s James Forman, Lewis agreed to eliminate those and other phrases, but believed that in its final form his address ‘‘was still a strong speech, very strong’’.

The March on Washington was not universally embraced. It was condemned by the Nation of Islam and Malcolm X who referred to it as ‘‘the Farce on Washington,’’ although he attended nonetheless. The executive board of the American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) declined to support the march, adopting a position of neutrality. Nevertheless, many constituent unions attended in substantial numbers.

The diversity of those in attendance was reflected in the event’s speakers and performers. They included singers Marian Anderson, Odetta, Joan Baez, and Bob Dylan; Little Rock civil rights veteran Daisy Lee Bates; actors Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee; American Jewish Congress president Rabbi Joachim Prinz; Randolph; UAW president Walter Reuther; march organizer Bayard Rustin; NAACP president Roy Wilkins; National Urban League president Whitney Young and SNCC leader John Lewis.

The day’s high point came when King took the podium toward the end of the event, and moved the Lincoln Memorial audience and live television viewers with what has come to be known as his ‘‘I Have a Dream’’ speech. King commented that ‘‘as television beamed the image of this extraordinary gathering across the border oceans, everyone who believed in man’s capacity to better himself had a moment of inspiration and confidence in the future of the human race,’’ and characterized the march as an ‘‘appropriate climax’’ to the summer’s events.

After the march, King and other civil rights leaders met with President Kennedy and Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson at the White House, where they discussed the need for bipartisan support of civil rights legislation. Though they were passed after Kennedy’s death, the provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 reflect the demands of the march.

Sources:

http://kingencyclopedia.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/encyclopedia/enc_march_on_washington_for_jobs_and_freedom/