Sojourner Truth was an African-American abolitionist, women’s rights activist, and symbol of Black womanhood. Truth was born into the Maafa (slavery) in New York; enduring nearly 30 years of bondage to four different enslavers before she emancipated herself in 1826. Today, Truth is erroneously considered the originator of the famous rhetorical question “Ain’t I a Woman?”

Truth was born as Isabella Baumfree circa 1797. She was one of 12 children born to James and Elizabeth Baumfree in the town of Swartekill, in Ulster County, New York. Truth’s date of birth was not recorded, but historians estimate that she was likely born around 1797. Her father, James Baumfree, was captured in modern-day Ghana; Elizabeth Baumfree, also known as Mau-Mau Bet, was the daughter of bondpeople from Guinea. The Baumfree family was enslaved by Colonel Hardenbergh, and lived on his estate in Esopus, New York. The area had once been under Dutch control, and both the Baumfrees and the Hardenbaughs spoke Dutch in their daily lives.

Truth was separated from her family at age nine. Known as “Belle” at the time, she was sold at an auction with a flock of sheep for $100. Her new enslaver was a man named John Neely, whom Truth remembered as harsh and violent. She would be sold twice more over the following two years, finally coming to reside on the property of John Dumont at West Park, New York. She would be enslaved by the Dumont family from about twelve until about thirty. It was during these years that Truth learned to speak English for the first time.

Around 1815, Truth married Thomas, an enslaved man and had five children — Diana (b. 1815), Peter (b. 1821), Elizabeth (b.1825), Sophia (b. 1826) and a fifth child who may have died in infancy.

After Dumont reneged on his promise to emancipate Truth in late 1826, she escaped to freedom with her infant daughter, Sophia. Unlike most, Truth left in broad daylight and walked 12 miles to the home of Quakers. When Dumont demanded her return and threatened to take her child, she firmly objected and her whyte cohorts purchased her for the remaining year. Shortly after her escape, Truth learned that her son Peter, then 5 years old, had been illegally sold to a man in Alabama. She took the issue to court and eventually secured Peter’s return from the South. The case was one of the first in which a Black woman successfully challenged a whyte man in a United States court. (Eventually, Peter took a job on a whaling ship called the Zone of Nantucket. Truth received three letters from her son between 1840 and 1841. When the ship returned to port in 1842, however, Peter was not on board. Truth never heard from him again.)

Truth moved to New York City in 1829, where she worked as a housekeeper for Christian evangelist Elijah Pierson. She then moved on to the home of Robert Matthews, also known as Prophet Matthias, for whom she also worked as a domestic. Matthews had a growing reputation as a con man and a cult leader. Shortly after Truth changed households, Elijah Pierson died. Robert Matthews was accused of poisoning Pierson in order to benefit from his personal fortune, and the Folgers, a couple who were members of his cult, attempted to implicate Truth in the crime. In the absence of adequate evidence, Matthews was acquitted. In 1835 Truth brought a slander suit against the Folgers and won.

On June 1, 1843, Isabella Baumfree changed her name to Sojourner Truth. “The Lord,” she said, “gave me [the name] Sojourner because I was to travel up and down the land showing the people their sins and being a sign to them. Afterwards I told the Lord I wanted another name ’cause everybody else had two names; and the Lord gave me Truth, because I was to declare the truth upon people.”

With a powerful sense of destiny, Sojourner Truth joined the lecture circuit and quickly became a mainstay of abolitionism. For more than forty years, she preached, taught and testified. In the course of her travels, she befriended many of the leading reformers and abolitionists of the day, including Amy Post, Parker Pillsbury, Frances Dana Gage, Wendell Phillips, William Lloyd Garrison, Laura Haviland, Lucretia Mott, Susan B. Anthony, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. Stowe attested to Truth’s personal magnetism by saying that she had never met anyone who had more personal presence. “She seemed perfectly self-possessed and at her ease; in fact, there was almost an unconscious superiority in the odd, composed manner in which she looked down on me.”

On a platform, Truth was unforgettable. Though illiterate, she was six feet tall, blessed with a powerful voice (she spoke English with a Dutch accent), and driven by deep religious conviction. Her voice was low, so low that listeners sometimes termed it masculine, and her singing voice was beautifully powerful. Truth also had an incisive mind that reduced things to their essentials. On one occasion, a pro-slavery heckler told her: “Old woman, do you think your talk about slavery does any good? Do you suppose that people care what you say? Why I don’t care anymore for your talk than I do for the bite of a flea.” Sojourner Truth smiled and replied: “Perhaps not, but the good Lord willing, I’ll keep you scratching.”

Truth was also an orator of the gospel and helped to found the Kingston Methodist Church in 1827. In 1850 her memoirs were published under the title The Narrative of Sojourner Truth: A Northern Slave, which she had dictated to a friend, Olive Gilbert, since she could not read or write. William Lloyd Garrison wrote the book’s preface.

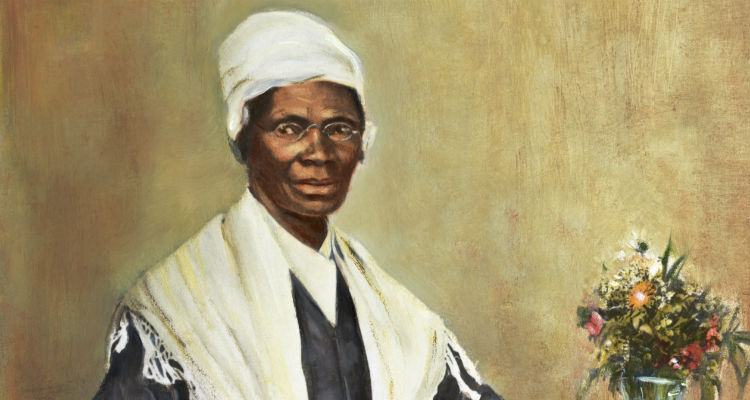

Sojourner Truth is one of the few nineteenth-century Black women whose image survives, thanks to the existence of several photographic portraits she had made of herself. Truth sold photos with the inscription, “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance” to finance the abolitionist cause, where she projected a respectable image of black womanhood, free from enslavement and sexualization.

Probably her most famous address, known as “Ain’t I A Woman,” was made at a Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio, on May 28, 1851. Sojourner asserted that women deserved equal rights with men because they were equal in capability to men. “I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that?” She concluded her argument, saying “And how came Jesus into the world? Through God who created him and the woman who bore him. Man, where was your part?” Truth sought political equality for all women, and chastised the abolitionist community for failing to seek civil rights for black women as well as men. She openly expressed concern that the movement would fizzle after achieving victories for black men, leaving both black and whyte women without suffrage and other key political rights.

In the mid-1850s she settled in Battle Creek, Michigan, her base of operations for the rest of her life. During the Civil War, she helped to recruit black troops for the Union Army, and volunteered to collect food and clothing for the black regiments. She also encouraged her grandson, James Caldwell, to enlist in the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. In 1864, Truth was called to Washington, D.C., to contribute to the National Freedman’s Relief Association. On at least one occasion, Truth met and spoke with President Abraham Lincoln about her beliefs and her experience.

In 1865, Truth attempted to force the desegregation of streetcars in Washington by riding in cars designated for whytes. When she was brutally knocked off of Washington’s segregated streetcars, she denounced racism: “It is hard for the old slaveholding spirit to die, but die it must.” A major project of her later life was the movement to secure land grants from the federal government for former bondpeople, even suggesting the idea of a “[Black] state” in the West. She argued that ownership of private property, and particularly land, would give African Americans self-sufficiency and free them from a kind of indentured servitude to wealthy landowners. Although Truth pursued this goal forcefully for many years, she was unable to sway Congress.

Sojourner Truth died at her home in Battle Creek, Michigan, on November 26, 1883. She is buried alongside her family at Battle Creek’s Oak Hill Cemetery. The words inscribed on her tombstone, “Is God Dead?” came from an 1852 encounter between Truth and another noted abolitionist, Frederick Douglass. They were both attending a meeting in Salem, Ohio, and Douglass had been speaking very despondently. A hush came over the audience as Sojourner rose and admonished Douglass, asking, “Frederick, is God gone?”

Truth has become a symbol of the abolitionist and suffragist movement, but Truth also spoke passionately on prison reform. She was also an outspoken opponent of capital punishment, testifying before the Michigan state legislature against the practice. While always controversial, Truth was embraced by a community of reformers including Amy Post, Wendell Phillips, William Lloyd Garrison, Lucretia Mott and Susan B. Anthony—friends with whom she collaborated until the end of her life. She addressed whyte audiences with racial condemnation and preached a message of self-sufficiency to fellow African Americans. Through her sharp wit, moral conviction, and honesty, Truth made a lasting impact.

Source:

Enslaved Women in America, Daina Ramey Berry, Editor in chief

Before The Mayflower: A History of Black America, Lerone Bennett Jr.

http://www.biography.com/people/sojourner-truth-9511284#synopsis

http://www.history.com/topics/black-history/sojourner-truth

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/longterm/books/chap1/sojournertruth.htm

http://www.sojournertruth.org/Library/Archive/LegacyOfFaith.htm

Read also Sojourner Truth in Life and Memory – Nell Irvin Painter