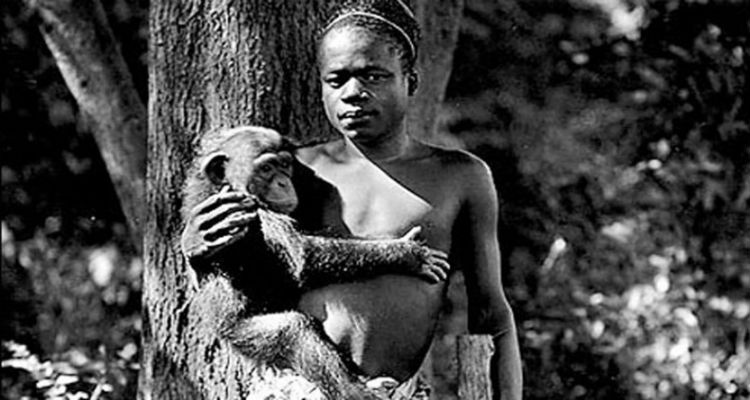

Ota Benga was a Congolese man taken from Africa to the US, where he was featured in an anthropology exhibit at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1904, and exhibited with monkeys in 1906 at the Bronx Zoo. On March 20, 1916, he shot himself in the heart while being held against his will in the United States.

Ota Benga was born in the Ituri Forest, in the extreme northeast of the country now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo, to the Mbuti people. His people were nomadic, moving from one temporary place to another as the seasons and hunting opportunities dictated. Benga married young and fathered two children. When he was still a teenager, the eastern Congo erupted into a war that saw mass deportations, raids by Arab slavers, and an invasion by the Force Publique, a Belgian-led occupying army originally formed by Leopold ll to ensure forced labor. They participated in mass killings,rapes and even collected severed hands and heads.

Sometime in the late 1890s, while he was out hunting, the Force Publique “soldiers” found Benga’s family camp and killed his entire family. Shortly after losing his family, Benga was captured by slave traders who put him in chains and dragged him out of the forest. He was forced to work as a laborer in an agricultural village. It was there, in 1904, that Benga encountered Samuel Phillips Verner, an American businessman in Africa who was tasked with acquiring a diminutive African to display as “missing links” in human evolution at the World’s Fair’s Louisiana Purchase Exposition. Verner bought Benga for a pound of salt and a bolt of cloth; later claiming that he had “saved” Benga from a cannibalistic tribe who had kidnapped him. Verner convinced Benga and, later, eight other African from the Batwa people to come to St. Louis.

Verner’s group brought Benga to St. Louis, where he became “the hit” of the 1904 World’s Fair.

To please the crowd, Benga and the other captive Africans began imitating the dancing and war-whoops they saw the nearby American Indians doing. He made friends with Geronimo and charged increasingly interested visitors five cents to see his teeth. At one point, the National Guard had to be called in to control the crowds because they were getting so large.

After the fair, Benga traveled with Verner and even returned to Africa for a time. In 1905, he took up residence with another Congolese people, the Batwa, and married a Batwa woman. The marriage only lasted a few months, ending when Benga’s wife died from a snakebite. Benga then traveled back to the United States with Verner in 1906.

Upon returning to the United States in 1906, Benga was taken to the American Museum of Natural History, where he again “delighted” visitors by pretending to be a babbling half-human. On one occasion he was asked to seat a wealthy donor’s wife. Benga pretended not to understand and threw the chair at her instead, just missing her.

Everybody at the museum liked Benga, but the director refused to pay Verner the salary he was asking for, so eventually Benga was moved to the Bronx Zoo, which was looking to expand its monkey house. Benga was allowed free movement through the zoo grounds, but his hammock was slung in the primate exhibit. He was displayed as part of the New York Anthropological Society’s exhibit on human evolution.

A sign outside the cage read:

The African Pygmy, Ota Benga

Age, 23 years. Height, 4 feet 11 inches.

Weight 103 pound. Brought from the Kasai River,

Congo Free State, South Central Africa,

By Dr Samuel P Verner.

Exhibited each afternoon during September

Benga’s presence in the zoo was so astonishing that on Monday 10 September 1906, the New York Times featured an article about him. Under the headline “Bushman Shares a Cage With Bronx Park Apes”, the paper reported that a so-called “pygmy” had been put on display in the monkey house of the city’s largest zoo; with crowds of up to 500 people gathering around the cage to gawk at him. Ota Benga – just under 5ft tall, weighing 103lb – would shoot his bow and arrow, or wove a mat and hammock from bundles of twine placed in the cage.

By the end of September, more than 220,000 people visited the zoo – twice as many as the same month a year earlier. Nearly all of them headed directly to the primate house to see Ota Benga.

The local African-American clergy were appalled by the exhibit and demanded Benga’s release, even lobbying the governor to force the zoo to shut down the display. Benga was eventually released into the custody of James Gordon, the minister who had led the charge to free him. He then went to live in Gordon’s African-American orphanage.

Still unhappy with his life, Benga eventually moved to Lynchburg, Virginia, to live with friends of Gordon named the McCrays. Gordon managed Benga’s affairs, and arranged to have his teeth capped and enrolled him in a school. He also got Benga a job at a local tobacco plant, where he seemed to have been popular and told his story for free root beer.

However, by 1914, Benga was planning to Africa. With the money he made from the tobacco job, Benga started putting things in order and looking for passage to the nearest port to his homeland. By this time, Leopold II was dead, and conditions were looking up in the Congo.

But this return passage was not to be. The outbreak of World War I suspended most cross-Atlantic shipping, and the German occupation of Belgium threw the Congo into bureaucratic chaos, with nobody allowed in or out.

On March 20, 1916, depressed at the thought of not being able to return home, Ota Benga fired a single bullet through his own heart.

Source:

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jun/03/the-man-who-was-caged-in-a-zoo

https://www.rt.com/news/336335-ota-benga-caged-pygmy/